Goldwater, Nixon, Reagan—Perlstein has moved from covering a minor saint, to a martyr, to God.

— David Weigel

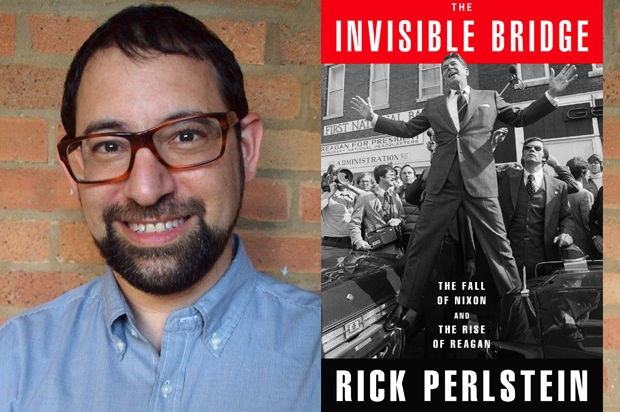

Weigel’s summary goes to the heart of why Rick Perlstein’s latest book, “The Invisible Bridge,” has been received so differently from his first two histories of modern conservatism. It’s not that Perlstein has changed, but the stature of his subject matter most certainly has. Barry Goldwater had long been a neglected, if not a forgotten historical figure, and Perlstein’s sharply observed account of his turn at the apex of American politics earned wide praise from conservatives for exactly the same reason that his account of Reagan’s rise has earned such enmity. A bogus plagiarism charge was even mounted to not only muddy the waters, but to actually try to prevent publication of his work.

Because the shift in conservatives’ attitudes has been so dramatic, fewer have noticed how others have also shifted. Perlstein, understandably, has picked up on it.

“My stupidest reviews come from centrists desperate to cling to myth of a sensible right,” he tweeted on Dec. 15, linking to his response to a review by Jacob Weisberg in the journal Democracy. Weisberg, not incidentally, is working on his own Reagan biography, but there’s something much deeper than preemptive turf war tensions brewing between them. And when UC Berkeley economist/econoblogger Brad DeLong tweeted back, “OK, I will grant you Jacob Weinberg. Who else?,” Perlstein responded, “Sam Tanenhaus. Damon Linker [here] (he wasn’t all that bad). Robert Kaiser [here],” clearly indicating he had a body of reviews in mind. (When Salon spoke with him, Perlstein added Geoffrey Kabaservice and Michael Kimmage to the list.)

Perlstein’s got a point. Dispelling centrist and progressive myths about the right has been one of his key motivating factors as a historian from the beginning, and nobody really likes having their myths smashed to pieces—though some mind a lot more than others. However, Perlstein’s myth busting is not just to “expose conservative hypocrisy” or some related concern, as some have mistakenly supposed, but to get centrists and progressives to actually see what conservatives are doing, and why it’s not hypocritical in light of their worldview and values. “To beat conservatism, grasshopper, learn to think like a conservative,” Perlstein wrote in a blog post I’ll return to below. Thus, far from distorting his vision with respect to conservatism, as his centrist critics suppose, Perlstein’s political commitments fuel his motivation to be accurate, precise and insightful.

All this seems to go right over his critics’ heads, and indeed much of their criticism devolved into methodological griping—some of it sloppy to the point of being grievously inaccurate. At first Perlstein expressed a reluctance to respond, when Salon contacted him. “I’m hesitant to say too much because it’s kind of ungrateful to complain about reviews. I really am flattered and thrilled,” he began, echoing his opening remarks in the Atlantic, when he responded to its review by Sam Tanenhaus, titled “The Gonzo Historian.” But he did open up, though he repeatedly qualified his remarks. “I’m getting reviewed in the Atlantic. I’m on the bestseller list, getting to travel around and write books. It ain’t that raw. But I don’t think he’s helping advance an understanding of what’s going on in America.… I don’t think it’s helping our historical discussion.”

The root of such thinking is at least twofold: first, a belief in a left-right political spectrum in which both sides are mirror reflections of one another, and second, a belief in a “balanced” center that can somehow maintain its elevated position above the fray, untouched by the sordid realm it’s irrevocably embedded in—what longtime journalism critic Jay Rosen mockingly describes as ”the view from nowhere.” It’s a weird contradictory pair of assumptions, each questionable in its own right, but which combine so awkwardly as to discourage any critical self-reflection. It is, in fact, its own strange mythic worldview—a point we’ll return to below.

“These people who identify themselves as non-ideological, or post-partisan, or centrist, position themselves as not interested in ideology, but they’re perfectly obsessed with ideology, they’re just drenched in ideology, because they’re always weighing every utterance of themselves or others for bias,” Perlstein observed. “If you believe that there must be some abstract idea of left or right… you’re always going to be taking an ideological temperature, instead of just seeing the text, clearly, and evaluating it on an invention evidentiary basis.”

Hence the repeatedly bubbling-up assumption that any critical remark he makes about Reagan must implicitly be praise for liberals, whose faults he is blind to, right? Er, not so much. “I’m not very nice to liberals,” Perlstein noted. “One of my reviewers said that Carter [in this book] is almost like a con man. I don’t have too many heroes in these books. Maybe Martin Luther King, he’s pretty much the only one.”

The reason is fairly simple: He’s not that enamored with power. “What gets a little creepy with this is Reagan’s a winner, right? And I suspect a lot of these guys identify with a winner. They identify with power. And I see my role as standing outside of power and trying to understand it.”

As a result, Perlstein said, “It’s fascinating to me, it kind of reminds me of Lionel Trilling’s old jape about conservatives, that they don’t have any real ideas, they’re just irritable mental gestures that resemble ideas, so there’s really not a lot of–it’s very reactive.”

Turning back to the tweet, and the “myth of a sensible right,” if we focus on the American right itself, what Perlstein is pointing out must surely be true—if the right were “sensible,” as centrists and progressives generally understand the term, they’d have packed up shop following Goldwater’s defeat. Not being “sensible” in those terms is part of their defining core. The interesting question, then, is just what does that mean? How do different sorts of logic work? If one sort of logic applies to “sensible”/“reasonable politics,” then what sort of logic applies to “insensible”/“unreasonable politics”—and this instance of it in particular?

Two things must be noted right away: First, that Perlstein is talking about the American right collectively, not about any one individual in particular. The behavior he’s referring to is what we can observe about how the actually existing American right behaves in situation after situation—doubling down in opposition to any kind of gun safety legislation after Newtown, for example, or refusing to pass comprehensive immigration reform after losing the 2012 election—when all “reasonable” expectations point directly in the opposite direction. Particular individual conservatives who do act reasonably certainly exist, and if they’re prominent enough they get publicly disowned for their troubles, unless they choose and manage a more graceful exit. The above-mentioned Damon Linker, author of “The Theocons,” is one such individual, and like several others has come to be seen as more of a centrist (think John Dean or Kevin Phillips, though not Bruce Bartlett), though that’s not where he began.

Second, that there’s nothing necessarily wrong with a political movement being “unreasonable”—it depends on what they’re being unreasonable about. After all, the leaders of black slave rebellions such as Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vessey and Nat Turner were surely unreasonable in their demands, and generations later, their unreasonableness triumphed. So merely noting that the American right is not sensible or reasonable does not automatically say nearly as much as some people seem to think about the subjects described; one must ask what they’re unreasonable about—and why. This is not an attempt to attack and slander, but to truly understand.

In his responses to Tanenhaus and Weisberg, Perlstein focused primarily on what they got wrong about his book descriptively—clearly demonstrable failures to accurately reflect the content they were commenting on. This is the most basic level on which a reviewer should be held to account. But his tweet points to a deeper argument that goes to the issue of overarching interpretation, and suggests a connection between the two—the constant ideological straining to assert the existence of a sensible right produces distorted readings of his work, with mundane sorts of careless misreading as one of its telltale consequences.

Of course, it’s one of centrism’s primary conceits that only those to its left or right are tainted by ideology, but just how the center escapes from the world of politics it’s in the center of—that, my friends, never gets explained. Instead, we get repeated displays of ideologically loaded assumptions—it’s just that the ideology involved is a centrist one. To show what I mean, here’s a passage from Weisberg’s review:

If he were willing to look more critically at the left, the way he does at the right, Perlstein might give more weight to the visible bridge of Reagan’s stated views. By the mid-1970s, the failures of Great Society liberalism were evident: Despite some popular and meaningful accomplishments like Medicaid, the poorly thought-out War on Poverty was arguably doing more harm than good. Broken welfare and public housing systems were not liberating the urban poor, but trapping a new underclass in a new kind of poverty. Crime, bad schools, and the threat of busing were driving the middle class away from America’s cities.

There are multiple problems with this passage, some of which can be illuminated by quoting from a March 2013 Perlstein blog post at the Nation on the Democrats’ internal ideological struggles, where he touches on this exact same period of time—along with references to other eras when related struggles raged. Because he’s not pre-committed to balancing powerful figures on “both sides” against one another, what he actually says completely escapes Weisberg’s mental universe, or at least so it would appear.

The end of the Vietnam War didn’t bring ideological unity back to the Democrats, Perlstein notes; rather “the first post-Vietnam election, post-Watergate, in 1974, inaugurated today’s order of battle between the right- and left-leaning wings of the party.” He writes that Reagan had warned that the influx of new Democrats elected that year—mostly from the suburbs–would lead to “a flood of expensive, spectacular, and ill-conceived legislation which can’t be derailed or even tempered by the voices of moderation,” but he turned out to be spectacularly wrong:

Thirty-six-year-old Gary Hart was more or less the ideologist of the bunch. His memoir of the McGovern presidential campaign, which he had managed two years earlier, called liberalism “near bankruptcy.”Time called him a “liberal.” “Traditional ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’ slogans,” he wrote back in an angry letter to the editor, “are simply not adequate to cope.” He said the best way out of the energy crisis was “to work together. There will be a lot more cooperative ventures between the environmentalists and the energy developers.” His stock speech, “The End of the New Deal,” argued that his party was hamstrung by the very ideology that was supposed to be its glory—that “if there is a problem, create an agency and throw money at the problem.” It included lines that could have come from Commentary, the neoconservative magazine Jerry Brown, who was friends with Hart, liked to read and quote. Like: “The ballyhooed War on Poverty succeeded only in raising the expectations, but not the living conditions, of the poor.” (That was false: the poverty rate was 17.3 percent when LBJ’s Economic Opportunity Act was enacted in 1964 and 11.2 percent as Gary Hart spoke.)

What this passage shows is that a) Perlstein is quite aware of the complexities Weisberg alludes to, b) as well as the policy lies woven into Weisberg’s recitation of the conventional wisdom retrospective on the era, but that c) these complexities were playing out within the Democratic Party, not in the GOP, the primary locus of political developments chronicled in “The Invisible Bridge,” where d) that book’s primary protagonist utterly failed to see the complexities that Weisberg claims are fatally missing from his story; e) moreover the fact that ideological centrists like Hart and Brown were the “new blood” in the Democratic Party fundamentally contradicted Reagan’s portrayal of how the Democrats were relentlessly pulling the country leftward to its doom.

Bottom line: Perlstein shows that a nuanced picture of political history can coexist perfectly well with a simultaneous tale of stark ideological polarization in a polity as large and complicated as America’s. If anything, this brief description of what was happening with the Democrats makes Perlstein’s case even stronger, since it provides precisely the sort of rich complexity his critics claim that he lacks. Moreover, just because his extended book project recounts the multi-decade history of a dominant sociopolitical movement, that does not mean for a minute that he thinks it exhausts the history of the era—it is those like Weisberg and Tanenhaus and others who misread him who are guilty of this confusion, not Perlstein.

But that leaves undiscussed the precise nature of the unreasonable right as Perlstein understands it—and this is precisely where his critics ought to have focused their attention, had they not been ideologically so befuddled. Of course, the right is not unreasonable in its own terms—but that’s just the point. The problem that Perlstein is pointing to is not so much a problem with the right—as his centrist critics mistake him to be saying—it’s a problem with the rest of us not understanding the nature of the right, what it’s up to, and what constitutes reasonable behavior in light of what it is. The fullest answer to that comes from Perlstein’s book project itself, of course. But he’s dealt with it frequently in other venues as well, including two series of blog posts at the Nation from 2013. The first, in early 2013, ran under the banner “Nothing New Under the Wingnut Sun,” and it illustrated how key features of the conservative movement today have been around for decades, but it includes commentary on why those features came into being in the first place. The second series, under the banner “Thinking Like a Conservative,” takes us deeper inside conservative thought processes, illuminating the perspective from which their actions are not unreasonable at all.

The first series consisted of five posts. The first dealt with survivalism, the stockpiling of guns, ammo and other supplies for the coming apocalypse; Perlstein began by citing some recent examples from the news, and then connected them back to a 1960s survivalist group called the “Minutemen,” which “claimed inspiration from a speech given by John F. Kennedy.”

The second post dealt with schoolbook panics, starting with a recent example targeting Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” in Fairfax County, Virginia, and looking back to the “classic 1970s textbook fight [that] unfolded in Kanawha County, West Virginia, in 1974,” where “the fight was eventually pursued by fundamentalist preachers who dynamited the school board building.”

The third post dealt with conservatives’ passion for reckless spending cuts, taking the sequester as its most up-to-date example, and looking all the way back to Reagan’s first term as governor, when his budget director, facing a deficit, proposed “a magical solution: a budget that consisted of little more than last year’s document with the added notation for each department, “less 10 percent reduction.” Reagan didn’t get it, of course, but the sequester mindset was already there.

The fourth post dealt with abhorrence of government-sponsored preschool education, starting with Obama’s naively optimistic proposal for universal pre-K funding. “The preschool backlash is one of the oldest stories in the history of ‘New Right’ organizing,” Perlstein wrote. “A bill proposing a national system of nursery schools, under the authorship of Minnesota Senator Walter Mondale, was on a glide-path to passage in 1971,” but it was derailed by a massive outpouring of negative mail generated by the nascent “family values” right, significantly before Roe v. Wade came down.

But in these posts, Perlstein did more than just highlight the repetitive nature of what, he also probed the why—critically, but sympathetically as well, at least intellectually. Here’s what he wrote in the post about survivalism, for example:

Let’s think about this: for generations we have shared our America with Americans who fear change, fear difference, fear you and me, fear everything falling apart. So much so that they organize their lives and politics around staving off the fear—which often entails taking political action that only makes America more fearful and dangerous in for everyone; which destroy the trust and love it takes to sustain communities; and who reinforce one another in their fear to such a degree that the less crazy among them surely play a positive role in spurring the more crazy to the kind of awful acts we see around us now. We need to better understand where that comes from, and why it is not going away.

This does more than merely offer insight into survivalism itself, or its role and influence in the broader American conservative movement. It puts you in touch with one of the central motivations of conservatism across cultures and time—its heightened negativity bias, or threat response.

The final post in this series dealt with conservatives’ affinity for minoritarianism, the conviction that conservatives are fit to rule even if they don’t actually win elections, or, as Perlstein titled the post, “Why Conservatives Think the Ends Justify the Means.” In that post, he points out that conservatives have taken on a wide range of anti-majoritarian strategies in recent years: gerrymandering, voter suppression, even the Hastert Rule, which effectively prevents a majority of the House of Representatives from passing legislation—comprehensive immigration reform, for example—if a vocal minority within the GOP caucus is opposed to it. Conservatives are quite comfortable going against majority rule, he argues, because they are committed to specific end results. He quotes from his own 2003 review of Eric Alterman’s book “What Liberal Media?” Regarding the difference between conservatives and liberals:

We Americans love to cite the “political spectrum” as the best way to classify ideologies. The metaphor is incorrect: it implies symmetry. But left and right today are not opposites. They are different species. It has to do with core principles. To put it abstractly, the right always has in mind a prescriptive vision of its ideal future world—a normative vision…If the stakes for liberals are fair procedures, the stakes for conservatives are last things: either humanity trends toward Grace, or it hurtles toward Armageddon.

It’s not that all conservatives want a theocracy at heart; there are different kinds of conservatives, after all. But they all share in this general tendency to see things dualistically in terms of immutable end results, which is psychologically quite satisfying, at the expense of commitment to democracy, which is always a somewhat messy affair. It is, quite simply, a mistake to keep thinking that conservatives are just liberals with a different set of policy preferences. “They are different species,” as Perlstein says. They inhabit different imagined worlds. And it’s not a sign of bias, or ideological distortion to recognize this. It’s a sign of realism, and sanity.

Perlstein dives even deeper in his series “Thinking Like a Conservative,” which revolves around a few key insights and some of their more salient consequences. For the most part, these are relatively easy to state, and even grasp, at least in theory, but grasping them in practice is far more difficult, evidently. For example, in the first one, on mass shootings and gun control, his point is simple—no amount of gun deaths like Sandy Hook will convince conservatives to change their minds, and convince them to embrace “common-sense” gun legislation, because their “common-sense” response was dramatically different from liberals’—the whole “good man with a gun” routine, in response to an ever-growing string of horrific shootings. This ties into what I’ve written before about the role of heightened negativity or threat bias driving conservatives, documented by cognitive scientists.

In later installments, Perlstein hits equally obvious, simple points in some examples, as when he discusses conservative thinking about government shutdowns, for example: “The mortal fear is that if government delivers the goods, the Republicans have no future. Even their pragmatists are nuts,” he writes. And relatedly, when it comes to “government dependency” Perlstein explained that conservatives really do believe “the old saw that the deal the Democrats supposedly offer African-Americans—you vote for us; we give you free stuff—returns them to ‘slavery,’” noting that “The first use of that metaphor I’ve identified was by Ronald Reagan in 1968,” and summarizing the bottom line thus: “conservatives are immune to charges of ‘immorality’ when it comes to denying citizens government services because they believe ‘hooking’ people on government services is profoundly immoral.” So kicking millions off of food stamps is the moral thing to do, no matter what the Gospels might say, and no matter how many children go to bed hungry.

But Perlstein also delved deeper into how conservatives keep managing contradictory public stances without suffering any sort of inner angst about it. His post on goalpost moving explained why there’s no contradiction in conservatives today ferociously attacking the Affordable Care Act, even though its basic architecture “matches a plan drawn up by the Heritage Foundation in the 1990s.” As Perlstein explained, “The Heritage plan was a tactic of a moment…an increment toward the real strategic goal of getting the government out of the healthcare business altogether… someday.”

Relatedly, Perlstein wrote about “time-biding,” to explain the sudden shift from broad bipartisan support for the Voting Rights Act as recently as 2006 to the surge of voter suppression efforts now, with no sign of letup, much less reversal since the Supreme Court eviscerated the VRA in Shelby County v. Holder:

Look. Conservatives are time-biders. And they understand, as Corey Robin explains in his indispensable book “The Reactionary Mind,” that the direction of human history is not on their side—that is why they are reactionaries—because, other things equal, civilization does tend towards more inclusion, more emancipation, more liberalism. They could not survive as a political tendency unless they clothed reaction in liberal raiment. You’ve seen that happen over and over again—like when people like Grover Norquist, whose aim is to roll back the entire welfare state, including Social Security, says what he’s really trying to do is save Social Security.

But they also can be quite plain about what they ultimately want and how to get there, in documents meant to be read by other conservatives—documents shot through with language about biding time, preparing the ground, going to the mattresses: of tactical patience in the service of strategic ends. “Hell,” as National Review publisher William Rusher put it in 1960, “the catacombs were good enough for the Christians.”

As with Social Security—which still hasn’t been “saved” to death, so, too, with voting rights, he patiently explained. Only in that case, the time is now ripe. Biding time in the catacombs is so over.

But one piece in the “Thinking Like a Conservative” series stood out in particular, one discussing epistemology and empathy, or lack thereof. Perlstein began by talking about a letter to the editor arguing “that rape culture is, in the writer’s words, ‘non-existent.’” He went on to observe, more generally:

Have you ever noticed how conservatives who say the most controversial things imaginable think no one actually disagrees with them?

They will admit that, yes, people might claim to disagree. But they will explain, if pressed, that those who do so are lying, or nuts, or utter the non-truths they utter out of a totalitarian will to power, or are poor benighted folks cowed or confused by those aforementioned totalitarians. (Which, of course, makes the person “finally” telling “the truth” a hero of bottomless courage.)…. A genuine right-winger will be so lacking in intellectual imagination—in cognitive empathy—that imagining how anyone could sincerely reason differently from them is virtually impossible.

It’s a fascinating piece in and of itself, but rereading it for this story, I couldn’t help but notice how the same lack of cognitive empathy can be seen in others as well—although not in such an extreme, cartoonish form. To begin with, why did Perlstein even write that series in the first place, if there wasn’t a need to overcome a lack of cognitive empathy on the part of progressives and centrists when it comes to understanding how conservatives think? What’s more, Perlstein’s centrist critics appear doubly afflicted: They fail to grasp how differently conservatives see things, and they fail to grasp what Perlstein is thinking when he writes about them. They might be quite surprised to learn, as Perlstein told me, “A lot of people have told me that when they read my book about Nixon they sympathized with Nixon for the first time. And felt even affection for him. Some have said the same thing about Reagan. And certainly about Goldwater.”

The most helpful framework I’ve discovered for dealing with such differences in how people see things is Karen Armstrong’s articulation of the mythos/logos distinction in explanatory systems of thought: logos deals with how things work in the world, while mythos deals with giving life meaning—and everything within life, as well. As knowledge advances, all logos converges into an all-encompassing framework, a process that increasingly threatens mythos, which responds in part by imitating logos, thus giving us Creationism, for example. But reactionary conservatives aren’t the only ones who make meaning of the world—we all do. We all have some form of mythos, however well-developed or broadly shared it may be—although Armstrong makes the point that mythos only fully comes to life in forms of ritual enactment.

For Perlstein’s centrist critics, as centrists, the idea that conservatives see the world differently is itself an extremist idea that must be rejected out of hand. But that simply reveals how limited their own mythos is—a mythos that pretends to be all-encompassing, because it “listens” to “both sides” even if (as the examples of these reviews reveal) it doesn’t actually understand either one of them.

For Perlstein, understanding the conservative mythos is absolutely essential—both for progressive activists who want to be politically successful, and for historians who want to get the history right. This insistence on seeing conservatism clearly does not reduce the richness and complexity of the world, as his critics assume. Just the opposite, in fact. It makes for a much richer, complicated story of what our history has been about.

“I like to say my books set presidents on the cover, but they’re not really about the president, they’re about us,” Perlstein said. “The presidents serve as kind of a whetstone to understand why those people came to the fore, what kind of the national mood they spoke to, and they help us understand the aspirations and fears of the electorate, which is what I seek to do.” One of the criticisms his critics have raised is that he’s indulging in a sea of popular media, rather than doing “real” historian’s work, which consists of minute studies in archives. But Perlstein sees this as yet another reflection of an elitist, power-worshiping ideology. Such thinking is “anti-populist,” he said, and “speaks to an urge to see and believe in a world in which elites do make decisions behind closed doors.”

Relatedly, in responding to Weisberg’s complaints about his omnivorous media-scouring methods, Perlstein defended his engagement with popular media by citing a very highbrow authority, with a distinctly humanist, populist touch:

I try to do it [history] the way my methodological guide, the British philosopher R.G. Collingwood, described the ideal in his 1946 masterpiece, “The Idea of History”: by providing the reader occasion to empathetically “re-enact” past thought.

There’s that stress on empathy again. You see it often enough, and you stop thinking that it’s an accident. You start thinking, maybe he’s on to something. Maybe I ought to try it out myself, see if I can figure out what he’s saying—and why.