A story about espionage, at its best, is a story about stretching the limits of human experience to the breaking point, over and over again. “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy,” John le Carré’s 1974 novel (which was made into an Oscar-nominated film starring Gary Oldman in 2011) is an example of the genre at its best—a deeply psychological thriller that examines what duplicity does to people. Even highly trained operatives can’t be made immune to the most basic pressures of humanity: the desire for love, for security, for meaning.

Le Carré’s hero Smiley, who is in so many other ways the antithesis to James Bond, is not without his own Achilles’ heel: his wife. And to emphasize that she’s more of a symbol or even a crutch for him than a real person, in the 2011 film, she never speaks except off-camera—she’s never even filmed head-on. She is Smiley’s blind spot; he can’t see her clearly, so neither can we.

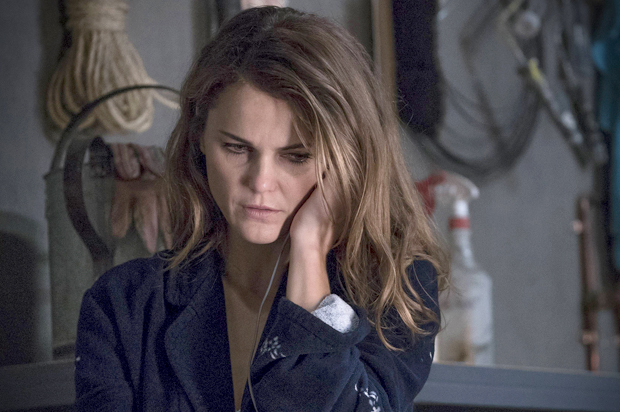

FX’s “The Americans” is not, perhaps, dismantling the Cold War as meditatively as “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.” But it has many of the same ideas—and instead of focusing on just one anti-Bond, it has a dozen. There are the leads Elizabeth and Philip Jennings (Keri Russell and Matthew Rhys), Soviet sleeper agents who are mild-mannered suburbanites by day and ruthless field operatives by night. There’s Stan Beeman (Noah Emmerich), an FBI agent who over the course of the first two seasons almost trashed his entire career for a Soviet double agent. There’s that double agent, too: Nina Sergeevna (Annet Mahendru), who is much more than just a pretty face. This isn’t a story with a hero—it’s an ecosystem of espionage. The players seem to change teams with frightening ease; everyone has a predictable set of pressure points—love, money, loyalty, pride. But while the characters have their blind spots, “The Americans” ensures that the audience won’t. If there’s no tuxedo-clad stranger who can swoop in to save the day, there’s also no unnamed woman who only laughs offscreen. There’s only the muddle of trying to make it to the next day in a world that keeps changing the rules.

That focus has made “The Americans” an unexpectedly humane show, in a setting that has played host to every kind of vapid action film. (The only match for vaguely Russian villains in American cinema are vaguely Nazi villains; double points if you can squeeze in both.) Indeed, in the first four episodes that open Season 3, the particulars of the Jennings’ mission in the United States feel even more rushed than ever. Though that’s a little distracting, it also underscores the show’s perspective. The purpose of the missions, the strategy behind them, even the stated goal, are delivered down from on high, from forces who aren’t on the ground. “The Americans” will often drop the audience into a mission we’ve heard nothing at all about before—all we can see are our leads in bad wigs and fake glasses, delivering their cover story to a clueless third party. It can feel a bit frustrating, like the show isn’t interested in actually telling the story of the mission. But on the other hand, it’s a surprisingly cogent parallel for how the agents themselves must feel—puppets privy only to the details necessary for them to carry out their mission.

It’s bad enough being a spy. It’s pretty awful being a spy with kids. That is, ultimately, what sets “The Americans” apart—Philip and Elizabeth are members of a family unit. The first season focused a bit more on the spies’ marriage, but by the second season, the focus of the show has been not just on being the puppet at the end of a string, but raising a puppet, too. In the last few episodes of Season 2, Philip and Elizabeth’s superiors revealed that they’re hoping for 14-year-old Paige to become a spy, like them. It’s one thing for two adults to struggle with questions of identity and meaning while killing people from the back of a stolen car. It’s another to grapple with offering up their child’s identity and sense of personal meaning for a fight that is increasingly losing all meaning.

“The Americans” has consistently been a show that brings violence and duplicity home. In Season 3, it’s becoming even more intimate. Without giving too much away, the first four episodes released to critics offer not just our leads’ concern over Paige’s life but also their differing opinions on it—a disagreement that starts rearing its head at the end of every other discussion. The audience is treated, also, to flashbacks of Elizabeth’s youth in Russia, and young motherhood with Paige.

Politicians and screenwriters are eager to invoke the love parents feel for their children—it’s so universal, so acceptable, so natural. Even if you don’t have kids, you were a kid, once. It’s a bond that’s deeply ingrained in our collective psyche, one of the relationships that makes us human. What “The Americans” offers is not just an exploration of that bond but also a reckoning of what it means to be a loving parent, a good parent, a role model. And, too, a glimpse of how forces beyond our control shape that relationship, one that feels so personal and sacred and yet is subject to the same pressures and whims as the rest of our lives are.

James Bond does not have children. It would spoil the fun: The point of those films, especially in Roger Moore’s heyday, is gadgetry, femme fatales, and Bond’s brand of witty one-liners and kicking ass while looking good in a suit. James Bond walks into enemy bastions and introduces himself by his full name; he doesn’t bother with disguising his British accent, his signature drink, or his rugged good looks. He has nothing to hide and nothing to lose, and his only responsibility is to his country.

The third season of “The Americans,” which debuts Wednesday night, offers no such pleasant fantasies. We all have something to lose. When you have children, the stakes are very high. So, the show asks: What are you going to teach your children, when the time comes? How will you explain to them what it means to be an American?