I was just a kid when my cousin Cuca passed away. I remember running around the living room of her house, one of those 1950s minimalistic box-shaped mansions in the affluent Mexico City neighborhood of Colonia Florida. The carpet is olive green, the wooden furniture classic and dark. Am I 7, 8? She’s sweet and serious, perched on the edge of the sofa with her hands pursed on her lap, watching me go mad, refraining from asking me to stop—her patience a laborious act of love.

It was in the early ’80s when she disappeared. I wasn’t even 12. Cuca was about to go on vacation, but she didn’t get to take the flight, never reached the airport. Kidnappings and disappearances were rare occurrences back then. No one could fathom where she was, or what could have happened to her.

You could say her ex-husband reported her absence to the authorities, but that would be inaccurate. In Mexico, those who can afford it know better than to call the police. Instead, he reached out to his government contacts. Within weeks, a team of state and federal law enforcement agents had tracked down and arrested Cuca’s gardener and housekeeper. They were lovers, it turned out, and they had confessed to kidnapping and murdering her.

I remember hiding behind the door of my parents’ room in disbelief as my dad broke the news to my mom. Police had found Cuca’s luxury sedan buried on an isolated mountain 55 miles west of Mexico City—her body inside the trunk of the car.

Cuca was the first person I knew to die this way. I struggled to imagine what must have gone through her mind in her final hours—the realization that she wouldn’t see her children again, that they would never know where she was when her life was taken. Her fate filled me with a sadness and horror I couldn’t articulate for years.

Only recently did I discuss Cuca’s kidnapping with my mother again, and she corrected my memory. The housekeeper and the gardener hadn’t meant to abduct her. They had intended to rob her house. Their mistake had been to strike as soon as they saw Cuca walk out the door. In fact, she had just made a quick visit to the supermarket to buy some last-minute essentials for her trip. Fifteen minutes later, she caught her own service helping themselves to her valuables. Amateur criminals, my mother said, they took her away in her own car and, after failing to cash a check for an unusually large amount they had forced her to sign, they strangled her.

My mother confirmed that Cuca had been found in the luggage compartment of her sedan. I asked if she recalled how she had been discovered, in what position. I wanted to know whether the image of my cousin’s corpse, folded perfectly in two like a flip cellphone, which kept me awake at night as a kid and haunts me to this day, was real or just the product of my obsession, my fright.

But Mom said no, “You didn’t make that up. That’s how she was found. They had folded her legs that way.”

* * *

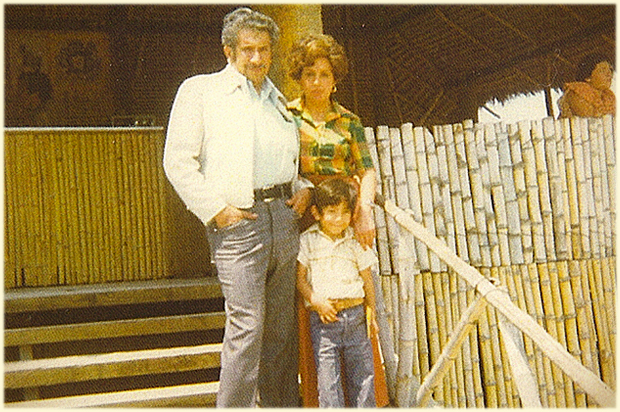

A couple of years after my cousin died, a yet rare wave of kidnappings struck the otherwise bucolic region of Dad’s hometown in the State of Mexico. Following the abduction of some of my father’s closer colleagues, friends and business partners urged him to get personal security.

My father loathed the idea of moving around with a bodyguard, but considered hiring a chauffeur who could ease the long hours he’d spend on the road every week while providing him protection—just in case.

A man in his mid-20s, who worked as a bus driver for the transportation company where my father was president, was brought to his attention. He possessed an uncommon personality that had made him equally admired and feared among his colleagues. Quiet and courteous, legend had it that every time he was challenged to a fight he would turn into an unflinching brute who annihilated his opponents with such savagery they would regret having messed with him.

His name was Guillermo and, like my father, he had been orphaned at an early age.

Tall and stocky, Guillermo had arms like trunks, long, thick eyelashes, a neatly trimmed, sturdy black mustache, and the sorrowful gaze of someone who’s never recovered from loss. He was affable, collected and resolute. Over time, he had developed a skin rash that would turn patches of his scalp bright purple and rugged. Mom said it was stress.

I was a fearful, lanky teenager who would hide from bullies and shy away from any form of boy-bonding violence at school when Guillermo started working for my father. Whenever I tagged along with my parents on business trips, he and I would share a hotel room.

Dad was 50 when I was born. His grandfatherly crow’s-feet, his pale sparrow thighs, the dull coffee-and-cream flannel PJs he’d wear to sleep–everything about his physical oldness made it hard for me to relate. But I remember looking up to Guillermo as he’d shyly strip off his clothes and slip in the bed next to mine in his underwear, trying to imagine him in one of those mythic fights that had earned him this job, struggling to believe what people claimed about him–that, if needed, he could kill a man with his own hands—longing to be as brave as he supposedly was, wishing to become as manly one day.

Guillermo worked as my father’s chauffeur for more than a decade, until Dad died of cancer in 1997. I never saw Guillermo fight once. In the end, he spent more time with my dad than I ever did.

The day of the funeral, Guillermo came to me as he’d never before, a child who has lost everything twice. “He died on us!” he wailed, as if he felt responsible for my father’s demise.

I wish I’d have said something to comfort him, but I didn’t. “Everybody dies, Guillermo,” I hissed, unable to cry as I would have liked to, despising him for his sudden weakness, for daring to assume his loss and mine were alike, for failing to prove we would be OK without Dad. I was 24, but I felt 14 again. Unlike Guillermo, I was becoming an orphan for the first time, and I’d never felt so vulnerable and terrified. I wondered how, and if, I would survive.

* * *

I grew up in Toluca, a small town 40 miles west of Mexico City. The house where I lived was located on an open street in an ordinary neighborhood. Back in the ’70s and ’80s, the Mexican middle class didn’t feel the urgency to live in gated communities patroled by private security.

Which is not to say that Mexico was safe. No country with such a wild gap between rich and poor can ever be. Little acts of abuse and brutality, from the miserable salaries housekeepers were paid to the never-ending stream of kids my own age begging on the streets, marked everyday life in my home country, but they didn’t register as despicable. You grow blind to violence when you experience it in small doses day after day.

One evening a couple of years before Dad passed away, Mom and I returned home from a shopping excursion in Mexico City, to find the main door to our house burst open.

Every drawer in the house had been pulled out—every cabinet and closet door hung ajar. In the studio, personal documents, books, and photo albums littered the oxford-gray marbled floor. TV sets, VCRs and the stereo had disappeared.

The safe in my parents’ walk-in closet had been compromised. Mom’s rings and necklaces and earrings were nowhere to be found. I remember her sitting on the edge of the bed with the empty jewelry box in her hands, sobbing bitterly.

In the safe drawer of my own room I only kept mementos—silly pictures with my school buddies; handwritten letters and Hallmark birthday cards from pals and ex-girlfriends; my collection of old “Star Wars” action figures. That drawer had been ravaged too, its contents scattered across the fawn carpet. Everything was there except for one dear picture. In the image, my best friend Ernesto—who’d moved to Tijuana after middle school—and I are leaning against the back of his rusty burnt orange VW Scirocco. We’re striving to appear tough and cool but we’re 16—we only get to look tender and naïve.

My stomach cramped as I shuffled through the jumble of keepsakes on the floor. When Mom asked if something was missing I said no, but I spent the night searching every corner. In growing panic, I wondered why the intruders had taken the photo, if this was a warning, their quiet way to tell us to keep our mouths shut, or if it was a more unsettling and rather inescapable possibility—that they would come back looking for me. Only when I found the picture stuck at the bottom of the closet hours later was I able to breathe normally again.

When my father returned home that evening, he said what everybody always does in Mexico after something like this happens: that we were OK and that was what mattered—that we had been lucky.

I guess we had. A few years before, when thieves broke into the house of uncle Jorge and aunt Nohemí, they had knocked out my cousin—who was just a baby sleeping in his crib—with chloroform to ensure he wouldn’t make noise. They had tied my uncle to a chair and forced my aunt to guide them to the valuables. In the nights that followed she said that she couldn’t sleep, thinking about the possible physical and psychological effects the assault would have on her son. She felt helpless. Shortly afterwards, they sold their house and moved to a gated community in the suburbs.

Following our robbery, my parents replaced the front door, installed white, sturdy metallic bars at the entrance to make it harder to breach, and reinforced the alarm system. But our sense of safety at home had been shattered.

When my father died, my mother refused to live there alone. She sold the house where I was raised, and built a new one in the same gated community where my uncles now lived.

* * *

When Dad passed away, I was living alone in Mexico City, in a small house my parents had bought when I moved to the capital for college. It was located at the end of a gated cul-de-sac with private security in the upper-middle-class neighborhood of Lomas de Tecamachalco.

The previous owner had installed bulletproof glass in every window and an imposing chain-link fence topped with barbed wire surrounded the house. “If someone wants to break into a home on this block,” he said to my father, who was wary about my moving to the capital, “this would be the very last one they’d choose.”

By the late ’90s, break-ins, stoplight muggings and kidnappings had grown prevalent in the city. Protection companies and makeshift guardhouses sprouted everywhere. Businessmen and politicians would shove forth through the streets in black armored Cadillacs or Mercedes Benzes–clunky white Dodge Spirits packed with jumpy armed bodyguards hot and bully on their trail.

By 2001 I was living in the same house, now with my wife. A few months before the birth of our firstborn, an obscure politician and his family moved to one of the largest houses in the cul-de-sac. We never spotted them, but whenever we’d see security escorts hanging out outside their house we knew he was home.

My son was just a handful of weeks old when my wife and I decided to take him out for a promenade. We were perhaps the only parents in the neighborhood who thought that taking a baby for a walk in the open air was a good idea. At the upscale shopping malls nearby, Interlomas or Santa Fe, it had become familiar to spot moms dressed to the nines strolling the aisles along with a housemaid in nurse uniform pushing the stroller and a scary-looking security escort trailing behind them.

As we walked by the politician’s house, one of his bodyguards in shirtsleeves was washing a black Chevrolet Suburban by hand. A semiautomatic handgun hung loosely from a shoulder holster as he reached for the shiny alloy wheels of the mammoth SUV with a damp cloth, oblivious of how close the gun was from slipping from his side.

I wondered what would happen if the holster slipped to the ground and a shot fired by accident. Who would I call for help if something happened to my son, my wife, and what would that bodyguard do if something happened to him–who could possibly help him, us?

It was a fleeting but defining lapse of reckoning about the future, about what the city, the country at large, had in store for my son, for me. I realized that the sense of security provided by fences and bars and private guards was artificial, and that fighting to maintain a privileged status in such an unfair society only generates more violence.

I had no choice but to accept what I had refused to for some time: that the only one responsible for protecting my child was me, that I was on my own now, and that raising my family in the same country where I grew up demanded an amount of bravery and denial I didn’t have.

Ever since high school, I had dreamed of living abroad, but only temporarily, as was customary among Mexican middle-class kids my age. One year in Boston to polish your English, perhaps another in Paris to learn some French—that would be nice, I thought. See other things, experience new places, if only to confirm the ideas that you were raised with—that you were lucky to have been born prosperous in a country where the majority are poor and neglected by the Establishment, that you were the Establishment—confirm that there’s no country like Mexico, and then come back home. I never once considered the possibility of one day fleeing.

I knew my father would have disapproved of my decision—Mom did at first. I knew he would have been ashamed to learn that his own son was this weak, this cowardly, this unpatriotic, but I couldn’t help it. I was afraid, and tired.

Three months later, my wife, my son, our stray dog, our Bengal cat and I, along with a few valuables, landed in Madrid. At first, I tried to live it as an exciting new chapter in my life. I was moving to Europe—who wouldn’t like to do that? The uncertainty of starting over in a foreign country, however, sank in pretty soon. I saw myself thousands of miles away from the land and the people I, in spite of it all, had never meant to leave behind, and I realized I didn’t know when, if ever, I would see them again.