THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGING

In a 1965 speech on “Youth and Sexual Behavior,” American sex education leader Mary Calderone quoted a recent hit song by a hugely popular folk artist. “Come mothers and fathers throughout the land, / And don’t criticize what you can’t understand,” Bob Dylan sang. “Your sons and your daughters are beyond your command, /The times they are a-changing.” He was right. Across the West—and, it appeared, in many parts of the East—sexual mores and behaviors were in flux. Surveys revealed that growing numbers of young people were having sex; in many places, venereal disease and out-of-wedlock pregnancies were also on the rise. So were pornographic images and literature, which encircled the globe as national censorship laws fell away. Coupled with antiwar protests and other youth-oriented political campaigns, the sexual revolution left young people in a “complicated state of uncertainty … on a wide international scale,” as one British commentator observed in 1969. Indeed, as a Swedish educator confirmed the following year, sexual behavior and standards were “a matter of considerable emotional charge all over the world.” So the real task for sex educators was to help develop a new set of mores, as Mary Calderone argued. Here she invoked an older and less contemporary figure in American letters, Walter Lippmann. “We are unsettled, to the very roots of our being,” Lippmann wrote, in a passage Calderone quoted. “There are no precedents to guide us, no wisdom that wasn’t made for a simpler age.”

Calderone’s own solution—“each must answer for himself”—simply reasked the question. The daughter of noted photographer Edward Steichen, Calderone attended medical school and became a director in the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. But her experiences in the family planning movement convinced her that Americans needed new attitudes toward sex, not simply new services or technologies. With a large bequest from the Rockefeller family, a key supporter of sex education since the early twentieth century, Calderone founded the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States in 1964 to promote more “rational” and “tolerant” viewpoints. Like other liberal educators around the world, Calderone often pointed to Sweden as a place where children learned about sex in a calm, matter-of-fact manner. But even the Swedes were divided—and confused—about the subject, as American sex educator Howard Hoyman observed. Prizing individual choice and decision making, the Swedes often declared “neutrality” on sexual issues, but they also stressed “mutual commitment and responsibility,” denouncing adultery and promiscuity. Around the world, Hoyman wrote, the “central issue” was “sexual permissiveness”: how much discretion should young people receive, and how—if at all—should adults try to guide them? Clearly, Hoyman noted, “horse and buggy sex education won’t do in the Space Age.” But it was far easier to declare a revolution than to decide what should come afterward.

The problem was especially acute in the developing world, where the infusion of Western literature, film, and television challenged long-standing ideas of sexual reticence and continence. “Hippies, Beatles and the like [sic] of them are visiting our country every day,” an Indian educator wrote in 1969, shortly after the Beatles’ “Fab Four” departed the country. “Most of our young people are now expressing their preferences for the liberalized sex mores and decrying the rigid traditions of our own society.” To some observers, such trends merely highlighted the need for sex education as a “preventive measure” against “greater liberty and experimentation,” as another Indian wrote; more than ever before, a Kenyan educator added, young people needed instruction about sex “before the damage is done.” Echoing sex educators in the West, other commentators urged schools to develop new standards instead of simply shoring up older ones. “We have to recognize that we are living in an age and in a society in which children are almost indoctrinated with the idea of sexual satisfaction as an ultimate axiom in life,” a principal in Hong Kong underlined. But educators still ignored sex, except for periodic warnings not to engage in it. “It is a world of contradictory attitudes, sexual indoctrination by the mass media on the one hand and a conspiracy of silence by [schools] on the other,” the principal wrote. “Can we blame young people if they are confused?”

For their own part, youth around the world demanded more discussion about sex in school. A special session on “Youth and Sex Education” at a 1967 family planning conference in Chile drew over two thousand young people, which was more than the venue could accommodate. Turned away at the door, the overflow crowd waited patiently to meet the speakers as they exited; inside, meanwhile, doctors and educators from four continents “frankly answered questions which doubtless have never before been asked at a public meeting in Latin America,” as one observer wrote. Even in the supposedly “advanced” countries of Europe and North America, however, students were alternately astonished, angered, and amused by the information—or, frequently, the mis-information—that they received about sex in their classrooms. In the Netherlands, “provos”—that is, youth rebels—demanded “honest” sex education and free contraceptives in the same breath as they denounced air pollution, South African apartheid, and the war in Vietnam. Likewise, Italian schoolgirls paraded through the streets of Rome to demand sex education alongside abortion rights. In the United States, finally, the New York Student Coalition for Relevant Sex Education demanded that each high school establish a “Rap Room” where students could receive accurate information about abortion, contraception, and other topics that the regular curriculum downplayed or ignored.

In a more radical vein, meanwhile, a German student magazine suggested that schools set aside “Love Rooms” for youth to obtain “practical experience” in sex itself. “Where does one find the peace to really enjoy each other without the permanent fear of being surprised at any minute?” the magazine asked. “At home?” Denouncing the standard curriculum as dated and irrelevant, some German students even stripped to the nude to demonstrate for more explicit sex education as well as contraceptive services in schools; others simply handed out birth control pills on their own. But their philosophy of sex was often less radical—and more romantic—than these agitprop events suggested. “Love should be the only motive for sexual intercourse at the beginning,” the German student magazine editorialized. “A girl who sacrifices her virginity should only do so for the sake of love.” Most of all, students said, they simply wanted schools to address sex openly and honestly. “Too many teachers give the once-over treatment, if any treatment at all,” an American high school student conference resolved in 1966. Fourteen years later, in 1980, another group of American high schoolers confirmed that little had changed. “All they do is show the same movie we’ve seen every year,” one of the students surmised. “You don’t learn anything new.”

SEX EDUCATION IN THE WEST: A REVOLUTION DEFERRED

As these comments illustrated, sex education changed much more slowly in the 1960s and 1970s than either the heralds or the critics of the sexual revolution imagined. In the United States and the United Kingdom, the number of children who received instruction in the subject rose steadily. By 1979, at least 90 percent of American schools provided some kind of sex education; the following year, 98 percent of British children reportedly received the same. As one British observer added, school biology courses—still the most common venue for sex education—increasingly focused on “the human reproductive system rather than that of the rabbit”; indeed, the high school biology syllabus included such formerly tabooed terms as semen, ejaculation, and ovulation. Even primary school pupils learned many of these words from sex education filmstrips and television shows produced by the British Broadcasting Corporation, which reached over a quarter-million children in three thousand schools by 1971. But sex education rarely moved beyond these “plumbing” lessons—as critics mockingly called them—to examine the social contexts and dilemmas of sex. Indeed, in most instances, there was no dilemma at all; even as they widened their sexual vocabulary, schools continued to instruct students to avoid sexual activity. The confused spirit of most sex education was vividly captured in American filmmaker Frederick Wiseman’s popular 1969 documentary, High School, which showed a visiting doctor making crude sex jokes to male students—all in the course of a lecture warning them to steer clear of sex.

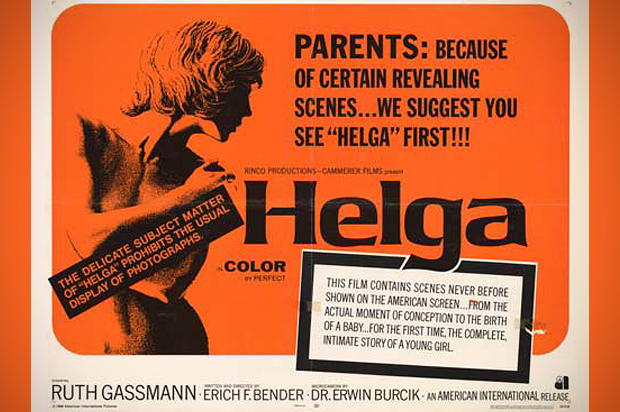

Elsewhere in the West, meanwhile, sex education varied with “local socio-cultural conditions,” as a 1975 study reported. The “most advanced” instruction took place in “liberal Protestant” nations, especially in Scandinavia and West Germany; the “slowest progress” was found in Catholic countries like Portugal, where high school biology textbooks still depicted human bodies without reproductive organs. French officials explicitly restricted sex education to “biological knowledge,” excluding questions of morality or values; here they drew less upon the country’s Catholic roots than on its tradition of laïcité, or state neutrality on religious matters. But even the supposedly liberal countries in northern Europe placed much more emphasis on pubertal changes and reproduction than on sexual mores and relationships, as the German example illustrates. Sex education received renewed attention with the 1967 release of Helga, a government-subsidized documentary aimed at creating a new consensus for the subject across West Germany’s different states and regions. The film opened with person-on-the-street interviews, showing adults reminiscing about their sexual ignorance as children. Then it provided the missing knowledge, including detailed descriptions of contraceptive methods and even a short clip of a live birth. As several commentators noted, though, the movie focused almost exclusively upon the biological aspects of sex; so did a subsequently released “Sex Atlas” for schools, which featured still photos from Helga. Indeed, a British journalist observed, a “Germanic coldness … ran through the entire film.”

Over the next few months, Helga became an international sensation; grossing a surprising $4 million in Germany alone, it was also a box office hit in about a dozen other Western countries. So it highlighted contrasts between different nations’ approaches to sexuality writ large. “While the French often regard sex as a game, the Danes, as a reality, the Swedes, as poetry,” a German observer wrote, commenting on the Helga craze, “the Germans seem to regard it as something to be analyzed—and explained and explained and explained.”

In the United States, where Helga’s popularity rivaled blockbusters like Paper Lion and The Boston Strangler, critics flayed the film—as well as its soft-porn sequel, Helga and the Sexual Revolution—as too “intellectual,” and too inattentive to social and emotional dynamics. Responding to such critiques, later editions of the German student “Sex Atlas” showed families playing with a newborn baby; they also discussed the working careers and parenting roles of the child’s mother and father. Likewise, courses and textbooks in the United States and United Kingdom gradually began to address “healthy relationships,” as one skeptical British author wrote in 1980, fueled by the faith that such instruction would solve everything from rising divorce rates to “football hooliganism.”

But almost all countries continued to avoid discussion of the “Big Four” taboos, as sex educators around the world called them: abortion, contraception, homosexuality, and masturbation. Just as “Problems of Democracy” courses generally ignored actual issues of democracy, one American philosopher wrote, so did sex education eschew the “real problems” of sex. Asked by a student which contraception method he would recommend to a sixteen-year-old girl, an American teacher curtly replied, “Sleep with your grandmother”; when the girl brought birth control pamphlets to school the following day, she was told that distributing them was illegal. Meanwhile, at least 80 percent of the world’s national educational systems ignored sex altogether, as one expert estimated in 1972. The previous year, the Spanish government blocked children from watching Adiós, cigüeña, adiós (“Goodbye, Stork, Goodbye”), Spain’s first sex education movie and a hit among adults; even children who acted in the film were barred from seeing it. Three Italian girls were investigated by prosecutors and forced to undergo medical examinations after publishing a 1966 article demanding sex education; eight years later, when another group of Italian students organized their own sex education course, local parish leaders denounced it. “Catholics, let’s act and make sure that here things will not be like they are in Denmark,” a parish leaflet blared, “where Catholic families no longer send their children to state schools where they only learn immorality.”

SCANDINAVIA: SYMBOL AND REALITY

To friends and foes alike, Scandinavia remained a symbol of progressive, liberal-minded sex education. International attention focused especially on Sweden, which had become the first country to require the subject back in 1956. As in the 1950s, much of this invective reflected right-wing stereotypes of “the typical Swede as a person with a bottle in one hand and a welfare check in another, wallowing in lust and sexual promiscuity, as he or she staggers along the brink of insanity and suicide,” as an American visitor quipped in 1971. But liberal sex educators and journalists across the world distorted Sweden and other Scandinavian nations, too, imagining them as united beacons of sexual openness, honesty, and dialogue. The movie Helga even included scenes from a sex education class in Sweden, asking German viewers if schools should provide Swedish-style instruction because many parents “did not know enough about their own bodies.” For most sex educators in the West, the answer was obvious: yes. American educators were especially prodigious in their praise of Sweden, noting its relatively low rates of rape, divorce, venereal disease, teen pregnancy, and abortion. They also made repeated trips to Sweden to study its sex education system and to meet with its revered leader, Elise Ottesen-Jensen, whom American allies saluted with a revealing nickname: “Great Lady.”

Elsewhere, too, liberal correspondents and visitors hailed Swedes and other Scandinavians as the world pacesetters in sex education. A British journalist marveled at the “frankness, confidence, and objectivity” of sex instruction in Denmark, which made the subject compulsory in 1970. In Sweden, meanwhile, the office mail of the RFSU—the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education—groaned with overseas appeals for information and advice. Some correspondents requested pornography, often in the guise of edification; in Japan, for example, a young teacher asked for pictures of female genitalia and a “small model of a woman’s waist,” so he could “study more harder.” But most foreign writers requested more substantial assistance—especially textbooks, pamphlets, and posters—to help bring their own countries up to the Swedish standard. “There is no sex education in our schools due to repressive attitude of Catholic Church,” a young Irishman complained, noting the surge of teen pregnancies in Dublin; in England, meanwhile, a biology teacher asked the RFSU to help him combat sexual prudery on his own shores. “We are about 20 years behind you in our educational approach to sex and morality,” the teacher wrote. Even a sex educator in the Netherlands—which would soon join Scandinavia as a global symbol of sexual openness—praised Sweden’s progressive policies, which stood head and shoulders above Dutch ones. “Our country is too conservative with regard to the sexuality,” he groused, requesting RFSU materials. “I am very interested in your way of working …which is so far with the sexuality.”

Scandinavian educators were more detailed and descriptive in their lessons about sex. In Denmark, for example, a junior high school textbook depicted male-female couples performing different sex acts “in softly lighted, decorously posed photographs,” as an astonished American reported. In 1965, the revised Swedish National Handbook on sex education included explicit discussions of contraception and abortion; a ninth grade test required students to define “sodomy” and “pedophilia”; and a top sex education official told a British interviewer that schools should provide “facts about sexual stimulation, sexual responses, and techniques of intercourse.” In practice, however, Swedish sex education remained far more limited than either advocates or critics assumed. Although the subject had been mandatory for over a decade, a 1967 survey reported that one-third of Swedish teenagers had not studied it; two years later, another scholar estimated that 30 to 50 percent of Swedish children received “inadequate or little or no sex education.” Moreover, the minimal instruction that students did get bore little resemblance to the candid, no-holds-barred spirit of the Scandinavian stereotype. A survey in the early 1970s showed that over half of fifteen-year-olds were still uncertain whether masturbation was “dangerous” or not; meanwhile, just over one-quarter of Swedish teachers had shown contraceptive devices to their students, as the national curriculum suggested. “Are we twenty-five years behind the Swedes?” American Lester Kirkendall asked in 1967, in the preface to a book by Swedish sex educator Birgitta Linner. “Or is it that Mrs. Linner and leaders like her are twenty-five years ahead of the rest of Sweden?”

Commonly invoked across the West, the metaphor of the race—with some nations “ahead,” and others “behind”—assumed that everyone was running toward the same finish line. So it also distorted the purposes of sex education in Sweden, which focused less on the perils of sex—a leading theme around the globe since the early 1900s—and more on its pleasures. Put simply, sex instruction aimed to help each individual develop a sex life that was personally meaningful and satisfying, and that goal came before broader social ones, including the protection of young people from disease and unwanted pregnancy. Asked by an Irish educator in 1978 how Swedish sex instruction reduced teen pregnancy and gonorrhea rates, RFSU chairman Carl Boethius freely admitted that Swedes “do not know if these positive figures are partly due to sex education.” But nor was that the purpose of such instruction, Boethius quickly added. “PS. The fundamental reason for sex education is—according to the Swedish view—the right to knowledge, not ideas about special effects,” Boethius wrote, in a scrawled note beneath his signature. Indeed, Boethius told another correspondent two years later, “the effects of sex education have never been studied in Sweden.” The only effect that mattered was deeply personal, and probably unmeasurable. “The best contribution of sex education is that the sexual act is now more often than previously experienced as a positive factor in the total relationship by both men and women,” Boethius explained. In the past, he noted, a well-known joke held that sex was a woman’s price for marriage, and marriage was what a man paid for sex. “There is nowadays little left of this deeply unhappy attitude,” he added.

Of course, there was no way to know whether this attitudinal change was attributable to sex education, any more than the incidence of teen pregnancy was. But Boethius’s comments spoke to the evolving goals of Swedish sex instruction, and also to the tensions between them. On the one hand, Swedes said, schools should help each individual experience sexual pleasure on his or her own terms; on the other, they should teach every individual that pleasure was a legitimate goal—even, a “right”—for all. Discarding the warnings against premarital sex that had marked older editions, the 1965 Sex Education Handbook described Sweden as a “pluralistic society … holding different views about sexual morality”; twelve years later, another revision said schools should aim to promote “sexuality as a source of happiness with another person.” But it also underscored the “common value” that everyone needed to share: the sexual sovereignty of each human being. “We do not put a stigma upon sexual relations before marriage,” a Swedish sex educator told an American correspondent in 1971. “Of course, we are presenting various kinds of questioning and a wide ideologi [sic] in these questions, but we do not press a sexual way of living as a model. The fundamental thing is that nobody should press anyone to do what he or she does not want to do.” Asked if schools should teach “a particular set of values or moral viewpoint,” another Swedish sex educator answered simply: no. “Who knows what are the right attitudes to develop in the young?” she replied.

THE CONSERVATIVE COUNTERREVOLUTION

To many adults, in Sweden and around the world, that question also had a simple answer: parents know. From its inception, of course, sex education had tried to supplant parental authority by intervening directly in a matter that was formerly reserved for families. But the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s heightened that tension, bringing more and more citizens into conflict with their schools. Ironically, sex educators often framed their project as a way to tame and discipline the more unseemly aspects of the revolution, especially the growing commercial trade of sexual images in advertising, film, and television; according to one Scottish advocate, school-based sex instruction would “meet the manifest needs of adolescents to be armed against the blandishments of the permissive-acquisitive society.” But to its growing cadre of conservative critics, sex education was a product of the same permissive trends it purportedly sought to halt. “Some educators say that we must have sex education because society is over-heated on the subject,” an American pastor told his church in a 1969 sermon. “But why are the schools seeking to add more fuel to the fire?” Modern society “already has a preoccupation with sex,” he added, so “it would appear to be compounding the problem to install sex in the classroom as well.” Indeed, a member of Great Britain’s National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association (NVLA) averred, sex education reflected “the filthiness of the Permissive Society.” Reversing these trends would require nothing less than a worldwide “sexual counter-revolution,” the group’s founder added.

The founder’s name was Mary Whitehouse, who was immortalized in a 1977 song by the British rock band Pink Floyd. “Hey you, Whitehouse / Ha ha, charade you are,” the band jibed. “You gotta stem the evil tide / And keep it all on the inside.” In the eyes of her liberal detractors, Whitehouse epitomized traditional middle-class British prudery, but she also became a hero to right-wing foes of the sexual revolution, first in the United Kingdom and then around the globe. Whitehouse was a schoolteacher in the 1930s and again in the 1950s and early 1960s, when she noticed that students were mimicking the new sexual banter they heard on the radio and television. She went on to create the NVLA, which focused most of its early fire on the British Broadcasting Corporation; when the BBC began producing filmstrips and TV shows for sex instruction in schools, Whitehouse started campaigning against sex education as well. Critics on the left condemned the BBC series as both too elliptical and too didactic; concealing or omitting important topics, it imposed a singular moral code that ignored human change and complexity. But to Whitehouse and her legions of followers, sex education was too detailed and not moralistic enough. “Your organisation is indeed extremely important at this moment of time, as a ‘voice’ for those thousands of decent folk, bewildered by the crude pressures on our sensibilities,” a British physician wrote Whitehouse in 1972. “I feel so sorry for the generation of teen-agers and what has been done to them in the name of ‘liberation.’”

Hundreds of similar missives arrived from elsewhere in Europe and North America, illustrating the increasingly cross-national character of the campaign against sex education. “It is like the Battle of Britain all over again,” a Canadian correspondent wrote Whitehouse, offering to come to the United Kingdom to assist her. “If England stands and recovers the whole world has a chance of returning to sanity.” Just as sex education supporters sought advice from the RFSU in Sweden, meanwhile, so did opponents write to Whitehouse and the NVLA for guidance on how to fight the subject in their own countries. Still others asked to join hands across borders and oceans, noting that a truly international crisis—the sexual revolution—would also require an international solution. “The big thing is that we all compare notes, ideas and thinking, and work as hard as we can to bring sanity to all our countries,” American activist Martha Rountree told Whitehouse. She was “not talking about one world,” Rountree quickly added, echoing the right-wing fear of the United Nations and “one-world government” during these years; nations will always exist, she emphasized, and it was “not realistic or expedient” to imagine otherwise. “But, if the right people in every Nation work together … the voice of the people in the world can bring about miracles,” she explained. “And, when I refer to the right people, I mean those who believe in God and their Country, who believe in the family unit, who hold high moral and ethical standards above the temptations that beckon at every turn.” Rountree urged Whitehouse to make another voyage to America, where they could “settle the world’s problems” together.

Here she alluded to Whitehouse’s highly publicized 1972 visit to the United States, sponsored by an American group called Citizens for Decent Literature (CDL) and its energetic founder, Charles Keating. A member of President Nixon’s National Commission on Obscenity and Pornography, Keating—like Whitehouse—had entered the political arena to fight sexual imagery in mass media; now he, too, was turning to sex education in the schools. At Whitehouse’s request, Keating had given the keynote address at the NVLA’s 1970 convention in the United Kingdom. Two years later he returned the invitation, organizing a whirlwind two-week North American tour for Mary Whitehouse. Her schedule for the trip reads like a veritable Who’s Who list of the burgeoning American New Right, featuring meetings with antiabortion crusader Phyllis Schlafly, journalist Fulton Lewis, and Catholic archbishop Fulton Sheen. “If ‘epistle’ is the feminine of ‘apostle’—then—you are a great epistle,” Sheen told her. Whitehouse also reunited with California congressman and conservative firebrand Robert Dornan, who had already met her during his own trip to the United Kingdom. Compared to Whitehouse’s expansive efforts, Dornan complained, the American New Right fell short. “He wonders—as I do—where is the Mary Whitehouse of America?” wrote CDL director Raymond Gauer, after talking with Dornan. “We sorely need a woman who can speak out intelligently, reasonably, forcibly and articulately against immorality.” Gauer added a nod to Carrie Nation, the nineteenth-century American prohibitionist who made her name attacking saloons with an axe. “That’s what we need today!” he exclaimed.

Whitehouse also traveled several times to Australia and New Zealand, under the auspices of the Festival of Light (FOL). Founded in London in 1971 by Whitehouse and several conservative compatriots, the FOL lit bonfires around the coastline of England to warn of “moral decay”—just as people did centuries earlier, to alert residents to threats of the Spanish Armada. Building on contemporary left-wing refrains, Whitehouse thrilled Australian audiences with her appeals to “people power” and “participatory democracy”; she also invoked the liberal-leaning environmental movement, calling on citizens around the globe to stamp out “moral pollution” alongside the industrial kind. New Zealand hosted representatives from another British anti-sex-education group, The Responsible Society, who warned listeners against going down “the slippery slope Britain has descended”; in Australia, meanwhile, visiting conservative luminaries from the United States—including Schlafly, Moral Majority founder Jerry Falwell, and Republican strategist Paul Weyrich—assisted in campaigns against abortion, pornography, and homosexual rights as well as against sex education. By the early 1980s, an appalled sex educator observed, right-wing groups in Australia had adopted many of the same “inventive acronyms” and “anything-goes tactics” that marked conservatives in America. Most of all, the campaign against sex education borrowed key conceptual frameworks from the Americans. “He who frames the issues helps to determine the outcome of the debate,” Weyrich told an Australian audience.

Excepted from “Too Hot to Handle: A Global History of Sex Education” by Jonathan Zimmerman. Copyright © 2015 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.