In early March, Matt Yglesias wrote a Vox article warning “American democracy is doomed,” not right away, perhaps, but eventually. The main reason, he argued, was the essential instability of our presidential system, in which both the president and Congress—especially the House—can plausibly claim popular legitimacy while opposing one another—a theory advanced by the late Yale professor Juan Linz back in 1990:

Since both the president and the Congress are directly elected by the people, they can both claim to speak for the people. When they have a serious disagreement, according to Linz, “there is no democratic principle on the basis of which it can be resolved.” The constitution offers no help in these cases, he wrote: “the mechanisms the constitution might provide are likely to prove too complicated and aridly legalistic to be of much force in the eyes of the electorate.”

There’s obviously something to be said for this idea, starkly contrasting potentially brittle and conflictual presidential systems with more fluid parliamentary ones. But as a systemic explanation, it tends to absolve individuals and groups of bad actors of any blame, and there very clearly are some bad actors involved in our politics. Both sides are not just doing the same thing.

There are pragmatic asymmetries as well: The kinds of policies advocated by each side are not equally suited to actual governing challenges. Denying the existence of climate change is not comparable to a preparing a response involving international emission-reduction agreements, domestic renewable energy policies and local planning. Finally, the presidential system explanation doesn’t tell us why this should become such a problem now. It’s not that America hasn’t faced serious systemic problems before—we had an extremely bloody Civil War, remember? But the presidential system wasn’t the problem. For a clearer picture of the dangers facing our democracy, we need to consider two other factors.

The first, which Yglesias also touched on, is what Harvard constitutional law professor Mark Tushnet (then at Georgetown) labeled “constitutional hardball” in a 2004 article. He defined it more succinctly in a 2014 blog post thus: “Constitutional hardball consists of practices that are constitutionally permissible but that breach previously accepted norms of political behavior, adopted to ensure the smooth functioning of a government in a two-party world, engaged in precisely to disrupt that smooth functioning.” He also wrote, originally, that the emergence of constitutional hardball “signals that political actors understand that they are in a position to put in place a new set of deep institutional arrangements of a sort I call a constitutional order.”

Conservative Republicans have been trying to change our constitutional order for a very long time now—at least since FDR’s first term—using whatever tools they could get their hands on, often quite destructively. As Yale constitutional law professor Jack Balkin pointed out in 2007 (more on this below), the Bush administration engaged in this practice quite extensively with three distinct periods.

It started with the use of hardball strategies (including illegal voter suppression) to get into office. It reached full expression in a multi-pronged “effort to expand executive power and limit Congressional and judicial oversight and executive accountability” in the pursuit of an endless global war on terror. And it concluded (after the post-2006 midterm losses) with a defensive phase intended to keep secrets, run out the clock, and preclude being held responsible for its illegal and unconstitutional practices.

Republicans have continued the practice since then, developing new strategies in congressional opposition. Tushnet developed the idea of constitutional orders in his 2003 book, “The New Constitutional Order,” which contrasts the older New Deal/Great Society constitutional order with its more minimalist neoliberal successor, which has been profoundly shaped by the extended period of divided government since 1968, a period unlike any other in our history, with just over 13 years of unified government, compared to 33 of divided government.

The second factor could be called the tendency toward apocalyptic conservatism, seen most clearly, nationally, in the repeated government shutdown threats, and threatened default on the national debt. While these threats essentially function as forms of constitutional hardball, they simultaneously express an attitude of profound alienation and animosity to the Lockean concept of the social contract. If the contract is destroyed as a result, so much the better, according to their logic. This tendency renders a significant faction of political actors essentially immune to persuasion in the national interest, which is obviously severely detrimental to the survival of a democracy.

At least three different tendencies contribute to this apocalyptic turn of mind. First is conservatives’ heightened negativity bias, their greater sense that it’s a dangerous world, with an endless supply of things to be afraid of. This overall tendency is then fed by two other tendencies: One is that conservatives are much less willing to compromise—as repeated polls (Gallup 2010/2011, Pew 2014) have found—the other is that their “solutions” (“trickle-down” economics, “abstinence-only” sex ed, “just say no” to drugs, etc.) are much less likely to work.

As a result, the more conservatives push and fail, the more likely they are to push even harder on even more ill-considered ideas, all against the backdrop of a threatening world, in which conspiratorial forces are at work—forces they can conveniently scapegoat as the real cause for their own failures. Breaking the system is a feature, not a bug, as both the militia movement of the 1990s and the Tea Party of today both believe.

As we settle in for a protracted struggle for the remainder of the Obama presidency, we need to become familiar with what all three factors entail—but especially constitutional hardball. But let’s start with the problem of a presidential system, and divided government, for two reasons: first to acknowledge its reality, and second to situate its problematic emergence historically.

As Yglesias explains, Linz observed that “aside from the United States, only Chile has managed a century and a half of relatively undisturbed constitutional continuity under presidential government — but Chilean democracy broke down in the 1970s.” He notes that various factors may be involved, but focuses specifically on “the nature of the checks and balances system” in a presidential system. All of which makes enough sense, but tells us nothing about the timing of crises. Nor does it explain what happened in Chile in 1973. The problem then wasn’t the Congress versus the president, it was Chile versus the U.S. That’s hardly an internal constitutional problem for Chile.

But it was part of a constitutional problem for America, overtly, the problem now shorthanded as “Watergate,” which actually involved a wide-ranging practice of lawlessness in the executive branch (involving “five successive and overlapping wars” as Woodward and Bernstein wrote 40 years later). It’s a practice Nixon began even before being elected, when he reached out to sabotage the Paris Peace Talks as a means to ensure his election, which is where Watergate apparently had its roots, as the “Plumbers” formed to burglarize the Brookings Institution vainly searching for Walt Rostow’s X-files on Nixon’s sabotage. Nixon’s 1968 victory was also the beginning of the divided government era—an historical landmark we should never lose sight of. In a structural sense, this was the underlying constitutional problem, and it was rooted in the Democratic presidential coalition’s loss of the “Solid South,” first evident in the 1948 election.

In their 40th anniversary retrospective, Woodward and Bernstein wrote, “At its most virulent, Watergate was a brazen and daring assault, led by Nixon himself, against the heart of American democracy: the Constitution, our system of free elections, the rule of law.” Such criminal intent goes well beyond “practices that are constitutionally permissible,” thus suggesting that Tushnet’s definition of constitutional hardball fails to penetrate the innermost motives, criminal and even pathological dynamics.

Yet, if constitutional hardball is about anything, it’s about changing the framework of norms that give moral, legal and ethical meaning to everything in our national lives, and Nixon’s pathological criminality was hyper-aggressively focused on changing those norms. At the time, Nixon’s lawlessness was thought to be an aberration, but it now seems more like the establishment of a new, somewhat sociopathic norm (“madman theory,” anyone?), particularly given how young Nixon hands Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney operated in the Bush administration 30 years later. In the interim, Cheney vigorously defended and covered up Reagan-era lawlessness in the Iran-Contra affair as well. Even more specifically, Nixon’s peace talks sabotage was echoed in electoral criminal activity for both Reagan (the alleged “October Surprise”) and George W. Bush (voter purges). The nitty-gritty political history of the past 40 years paints a much more lurid picture of what constitutional hardball looks like in the real world than Tushnet’s levelheaded definition might suggest.

Tushnet’s book focuses on two contrasting “constitutional orders,” and makes it clear that the second one is significantly defined by divided government. They are the New Deal/Great Society constitutional order (created by overwhelming Democratic majorities), which he defined by citing FDR’s 1944 State of the Union, which “called for implementing a ‘Second Bill of [social and economic] Rights’” and the minimalist neoliberal state implied by Clinton’s declaration that ‘the era of big government is over.”

FDR’s elaboration of rights “included ‘the right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation’ and rights to ‘adequate medical care,’ ‘a decent home,’ and ‘a good education,’ as well as ‘the right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment.’” FDR’s 1944 State of the Union “defined the guiding principles of the constitutional order that prevailed from the 1930s to the 1980s,” Tushnet wrote.

In contrast, “Clinton’s claim that the age of big government had passed did not mean that the national government had nothing left to do. Rather, the initiatives of the new constitutional order would be small-scale,” Tushnet explained, and went on to say:

In the most general terms, the principles that guide the new constitutional order make it one in which the aspiration to achieving justice directly through law has been substantially chastened. Individual responsibility and market processes, not national legislation identifying and seeking to promote justice, have become the means by which that aspiration is to be achieved. Law, including constitutional law, does not disappear, but it plays a less direct role in achieving justice in the new constitutional order than it did in the New Deal–Great Society regime…. The new order’s vision of justice, that is, is one in which government provides the structure for individuals to advance their own visions of justice.

In short, the neoliberal minimalism of Clinton’s policy vision is itself a product of the persistent condition of divided government, and that neoliberalism has substantially replaced New Deal liberalism—the Americanized form of social democracy—within the Democratic Party.

Further underscoring the significance of the divided government constitutional order, Tushnet differentiates himself from views advanced by two other constitutional scholars, Jack Balkin and Sander Levinson, whose theory of “partisan entrenchment” revolves around the appointment of judges who establish a new constitutional order. In “Understanding the Constitutional Revolution” they write, “According to our theory of partisan entrenchment, each party has the political ‘right’ to entrench its vision of the Constitution in the judiciary if it wins a sufficient number of elections.” In response, Balkin explains:

Balkin and Levinson frame their essay with Bush v. Gore in the background, for they take that case, which installed George W. Bush in the presidency, as a step in the direction of partisan entrenchment. As they see the case, the Supreme Court’s conservative justices took steps to ensure that the next justices to be appointed would consolidate Republican control of the courts and thereby complete the partisan entrenchment that constitutes a constitutional revolution….

The emphasis Balkin and Levinson place on partisan entrenchment, however, means that they cannot consider the possibility, developed in this book, that a constitutional regime can be characterized by persistent divided government, and that divided government produces policies with their own guiding principles.

In my view, both Tushnet and Balkin/Levinson have a strong point. Indeed, part of what makes things much easier for Republicans in this era is that—with few exceptions—they’re not going up against FDR-style social democrats, with the full-bodied set of attitudes, assumptions, principles and expectations entailed in that constitutional order, but instead face neoliberal Democrats who desire compromise in a framework of diminished expectations. Thus, it’s both true that we’ve experienced the transition in constitutional orders that Tushnet describes and that Republicans continue pushing for yet another transition in constitutional orders, to the end-point of the sort partisan entrenchment that Balkin/Levinson described. (This helps explain why “both sides” are not the same in today’s politics. Democrats have internalized the values of a divided government constitutional order, and don’t even use strongly partisan proposals as bargaining chips. Republicans are still pushing for a radically different constitutional order in the future, and are willing to blow everything up if they don’t get their way, because psycho-politically, they don’t feel they have anything to lose.)

Balkin himself seems to have adopted such a more-inclusive view by July 2007, when he wrote, “Constitutional Hardball in the Bush Administration,” at his influential Balkinization blog. Balkin explains his adoption of Tushnet’s idea, and its application to recent history as follows:

We might divide the Bush Administration’s practices of constitutional hardball into three categories. The first are acts used to gain power. The second are acts used to attempt to transform the government into a new constitutional order. The third are acts designed to head off accountability following the failure of the attempt. The second set fit most closely Mark’s original model of constitutional hardball. But the first and third set are equally important for understanding the phenomenon.

The first category includes voter purges that were illegal under the Voting Rights Act, in addition to the “implausible arguments that maintained the outward forms of law” supporting the Supreme Court’s Bush v. Gore decision.

As for the second category, Balkin writes:

Once in office, Bush engaged in a second round of constitutional hardball. He pushed the legal envelope repeatedly following 9/11 in an effort to expand executive power and limit Congressional and judicial oversight and executive accountability. The list of examples is seemingly endless. The most obvious examples are, in no particular order, (1) the Administration’s fetish with secrecy, (2) its use of Presidential signing statements to signal to executive branch officials to disregard certain features of law outside of public view, (3) its claim that the President has the power to round up people (including American citizens) and detain them indefinitely without any of the protections of habeas corpus or the Bill of Rights, (4) its domestic spying operations, (5) its detention and interrogation practices, including its system of secret CIA prisons, (6) its theory that the President does not have to obey Congressional statutes when he acts as Commander-in-Chief, and (7) its alternative theory that the September 18th, 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force gives the President a blank check to do whatever he wants.

Balkin argues that the combination of “an expansive (some would say limitless) conception of Presidential power” justified by a state of emergency, and the lack of any endpoint to the emergency “was, in effect, the declaration of a permanent state of emergency.” (Although he does not mention it, this has, in fact, become part of the divided government constitutional order, since Obama has effectively just accepted it, despite the occasional tut-tutting.) He argues:

This set of acts of constitutional hardball is closest to Mark’s original model of why government actors engage in constitutional hardball– they want to create a new constitutional regime that lasts for many years. Had the Iraq war not failed miserably due to the incompetence of President Bush and members of his Administration, he might well have succeeded. If he had succeeded, his actions would be blessed by history. People would make excuses for them, or, better still, these actions would become correct constitutional practice in the new regime.

But, of course, the Iraq War did fail, and the Democrats regained control of Congress in the 2006 midterms. This led to the third round of constitutional hardball, the coverup phase, with Bush “pushing the constitutional envelope by offering an expansive theory of executive privilege. He asserts, among other things, that he has the right to order individuals who no longer work for him to refuse to testify before Congress even though this violates the law.”

This third round only happened “because Bush’s previous acts of constitutional hardball did not take,” Balkin argues:

He was not able to create a new constitutional regime that would maintain his party in a dominant position for the foreseeable future. He was not able to bootstrap actions of dubious legality into widespread acceptance and thus enjoy the benefits of winner’s history and winner’s constitutions. Instead, things are now crumbling about him and there is a very significant chance that his party will suffer for his miscalculations during the next few election cycles.

Looking forward, then, Balkin cited three things that “matter above all others”: keeping secret what the administration has done relative to the above, running out the clock “to prevent any significant dismantling of his policies until his term ends,” and ensuring there will be no future accountability.

Look back at this observation some eight years later, one thing that’s particularly striking is how little effort there was to hold anyone accountable. And this is where we can take note of a profound asymmetry in how constitutional hardball has been played over the period of the past 25 years: just as the “extra-legal” activities of the Reagan/Bush administration were given a pass in the end, rationalized by tropes such as saying the nation couldn’t handle “another Watergate,”under Obama we were treated to the rhetoric of “looking forward, not backward.”

However, even as Obama went out of his way to make nice with Republicans, they responded with an onslaught of constitutional hardball moves, mostly falling into three broad categories. First, most directly, congressional Republicans acted to obstruct the basic functioning of his presidency. They had little power to do anything along these lines in the House before winning the 2010 midterms, so the obstructionism began in the Senate, where the obstruction of Obama’s presidential nominees reached such unprecedented levels that it finally led Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid—a staunch institutionalist, deeply resistant to changing Senate rules—to push through a rule change in November 2013. As Kevin Drum wrote at the time:

[I]t was Republican filibusters of judicial and executive-branch nominees that finally drove Democrats to act on Thursday. Democrats had struck one deal after another with Republicans to try and rein in their abuse of the filibuster, but nothing worked. A few nominees would get through, and then another batch would promptly get filibustered….

The last straw came when Republicans announced their intention to filibuster all of Obama’s nominees to the DC circuit court simply because they didn’t want a Democratic president to be able to fill any more vacancies. At that point, even moderate Democrats had finally had enough. For all practical purposes, Republicans had declared war on Obama’s very legitimacy as president, forbidding him from carrying out a core constitutional duty.

Reid himself put out a graphic saying that 82 presidential nominees have been blocked under President Barack Obama, 86 blocked under all other presidents, but when Politifact fact-checked him, it turned out to be even worse than Reid had said. Reid was counting individual cloture votes, which some nominees had more than one of. Politifact went on to say:

By our calculation, there were actually 68 individual nominees blocked prior to Obama taking office and 79 (so far) during Obama’s term, for a total of 147.

Reid’s point is actually a bit stronger using these these revised numbers.

In short, Obama had more nominees blocked prior to the rule change than all other presidents before him combined. That’s the very definition of constitutional hardball in the Senate.

Not to be outdone, House Republicans brought America right to the brink of its first debt default in history in July 2011, and shut the government down for two weeks in October 2013. The debt ceiling had never been the subject of such legislative blackmail before. The shutdown strategy (as opposed to brief, partial lapses) had been used just once previously—by Newt Gingrich, disastrously, in late 1995 and early 1996. There have been repeated threats to engage in both tactics again. The overall aim of these legislative obstructions was to bring everything to a halt, to make Obama’s presidency a complete failure—rather like George W. Bush’s had been. In addition to the high-profile examples just cited, after the GOP won the 2010 House midterms, the of legislating fell far below that of the notorious “do-nothing Congress” that Harry Truman ran against in 1948.

The GOP’s second major front of constitutional hardball in the Obama era has been the attack on voting rights centered in state legislatures, as Republicans took actions to deprive Democratic voting blocks of fair representation. They both proposed and passed a massive outpouring of voter-suppression laws, which clearly have the power to shift electoral outcomes at all levels.

As I wrote here in December, a Republican fantasy is to change how electoral votes are allocated in these states, and tie them to congressional districts rather than state popular votes. Under that plan, Mitt Romney would be president today, despite his solid defeat by Barack Obama in both the popular and electoral vote. Writing about the first wave of such activity in early 2013, Jonathan Bernstein called it exactly what it was: “Playing Constitutional Hardball With the Electoral College.”

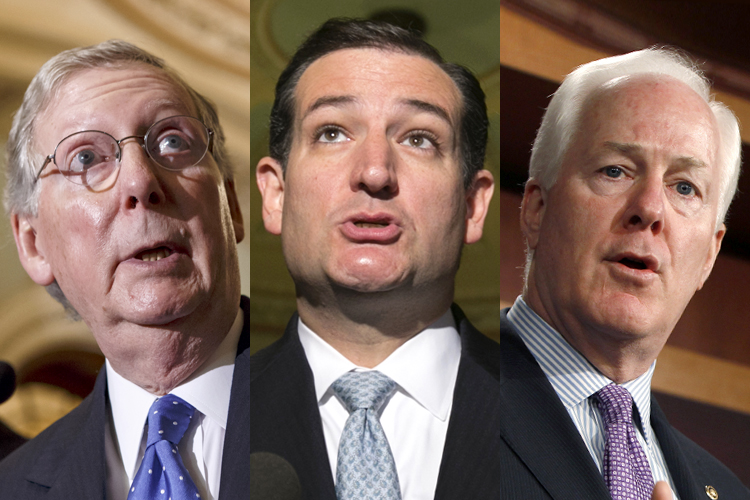

There are desires afoot to play constitutional hardball in the age of Obama that go well beyond what’s been actually advanced. These range from sporadic enthusiasm for secession to a more sustained, though still marginal interest in using state legislatures to rewrite the Constitution. As I explained here in January 2014, this plan, if successful, could give 12 percent of the population control of writing new constitutional law. Connecting these still-fringe ideas to the mainstream is the legitimating ethos that sustains them both, an ethos epitomized by birtherism, which now has a solid majority of GOP voters doubting Obama’s citizenship, and hence, the legitimacy of his presidency. The birther mythos is the ultimate justification for constitutional hardball in opposing Obama. Of course, it’s also palpably absurd, as Sen. Ted Cruz running for president now forcefully reminds all of his ardent supporters: being born abroad has absolutely no impact on the citizenship status of a baby born to a U.S. citizen. It’s true of Cruz, and of John McCain—both of whom were born abroad, and it’s true of Barack Obama, as well, even if he had been … which, of course, he wasn’t.

In short, the birther hysteria over Obama is perhaps the sharpest reminded of just how radical the GOP’s commitment to constitutional hardball really is. But it hardly stands in isolation. Even as the Clinton/Obama neoliberal Democrats of the past 25 years have generally taken Eisenhower-like positions, at most, their Republican opponents have viewed them in the most radical of terms—Obama as “a socialist,” Hillary Clinton as “a radical feminist,” etc. This is partly a matter of projection, and partly a reflection of the tendency toward apocalyptic conservatism mentioned above, which renders a significant faction of political actors essentially hostile to persuasion in the national interest—a significant threat to the survival of a democracy.

The more conservatives push, fail, double down and repeat, the more intensely they feel set upon by dark forces they can scapegoat as the real cause for everything that’s gone wrong with America, their lives and their world.

These tendencies combine to produce a powerful psycho-political dynamic, quite independent of anything in the real world. They have to be taken very seriously psycho-politically, because of the hold they have on sizable groups of people, but that should not lead us to take seriously any of the spurious factual claims they advance, up to and including the claim that Democrats are playing constitutional hardball with anything remotely approaching the intensity of Republicans.

We recently were given a sharp reminder of the worldview these people inhabit, when former Sen. Rick Santorum got an earful from a woman who doubtless spoke for millions of others in the paranoid GOP base when she said the following, combining fragments of conspiracy theory with exhortations to constitutional hardball of the highest order:

The American people put Republicans back in office in the House and the Senate, the two things we asked y’all to do was shut down Obama’s executive amnesty and shut down Obamacare, and you let us down on both issues. Why is the Congress rolling over and letting this communist dictator destroy my country? Y’all know what he is, and I know what he is. I want him out of the White House. He’s not a citizen. He could have been removed a long time ago.

Larry Klayman’s going to get the judge to say that the executive amnesty is illegal. Everything he does is illegal. He’s trying to destroy the United States. The Congress knows this. What kind of games is the Congress of the United States playing with the citizens of the United States? Y’all need to work for us, not for the lobbyists that pay your salaries. Get on board, let’s stop all of this, let’s save America.

What’s going on — Senator Santorum, where do we go from here? Ted told me I’ve got to wait now until the next election. I don’t the country will be around for the next election. Obama tried to blow up a nuke in Charleston a few months ago, and the three admirals and generals – he has totally destroyed our military, he’s fired all the generals and all the admirals that said they wouldn’t fire on the American people if you asked them to do so, if he wanted to take the guns away from them. This man is a communist dictator. We need him out of the White House now.

Crazed rants like that do not exist in a vacuum, they are carefully nurtured over time. Fifty years ago, William F. Buckley thought it absolutely necessary to officially purge the conservative movement of fringier elements, personified by John Birch Society founder Robert Welch, in advance of Goldwater’s presidential run in 1964. But in reality, Buckley was simply engaged in public theater. Those fringier elements never really went anywhere. Conspiracist tracts like Phyllis Schlafly’s “A Choice, Not an Echo,” John A. Stormer’s “None Dare Call It Treason,” and even David Noebel’s “Communism, Hypnotism and the Beatles” sold far more copies than Buckley did at the time. But at least Buckley created the illusory veneer of respectability. Fifty years ago, that crazy lady, and legions like her were Buckley’s problem. Now, they’re America’s problem. And there’s nothing remotely like them on the left.

Matt Yglesias is right about the structural problems of America’s presidential system. But compared to the Nixonian problems of constitutional hardball, and the swelling ranks of take-no-prisoners apocalyptic conservatives, there’s something almost genteel about the civics problems that have him so worried. It’s only when all three problems are considered together that we get an accurate picture of the profound civic danger we find ourselves in.