In the late 1850s, Walt Whitman wrote a series of poems celebrating what he called “manly love,” the love men had for other men. Whitman included the poems in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass under the heading “Calamus,” a plant with a suggestive, phallic-shaped flowering spike growing out of it. As I discuss in the next chapter, the exact nature of this manly love—essentially, whether it involved genitals or not—remains very much unsettled. In any case, Whitman wanted a series of poems that would counterbalance the “Calamus” ones. Whereas “Calamus” would celebrate the love of men for men, these new poems would celebrate the erotic love between men and women. The poems, Whitman imagined, would be “full of animal fire, tender, burning,—the tremulous ache, delicious, yet such torment. The swelling elate and vehement, that will not be denied.” To assemble the series, which he eventually called “Children of Adam,” Whitman gathered three poems from the 1855 and 1856 editions of Leaves of Grass, including the justly famous “I Sing the Body Electric” and the perennially controversial “A Woman Waits for Me,” and wrote another dozen shorter poems.

Among these shorter lyrics is the eighth poem in the series, later given the title “Native Moments.” By “native,” Whitman means a couple of things: inborn or innate, but also simple, natural, without affectation—possibly even uncivilized. To put it simply, he is talking about moments of overwhelming sexual desire, which, he believes, are native (instinctual) to us and native (almost crude) in and of themselves. Either way, these moments cannot and should not be denied. Whitman writes:

Native moments! when you come upon me—Ah you are here now!

Give me now libidinous joys only!

Give me the drench of my passions! Give me life coarse and rank!

To-day, I go consort with nature’s darlings—to-night too,

I am for those who believe in loose delights—I share the midnight orgies of young men,

I dance with the dancers, and drink with the drinkers,

The echoes ring with our indecent calls,

I take for my love some prostitute—I pick out some low person for my dearest friend,

He shall be lawless, rude, illiterate—he shall be one condemned by others for deeds done;

I will play a part no longer—Why should I exile myself from my companions?

O you shunned persons! I at least do not shun you,

I come forthwith in your midst—I will be your poet,

I will be more to you than to any of the rest.

In many of his poems, Whitman defiantly takes up for slaves, prostitutes, and assorted social outcasts. In this poem, he takes up “for those who believe in loose delights,” for the young men who engage in “midnight orgies.” Whitman vows to become the poet of these young men because he wants to include everyone—and everything—in his poetry, especially those whom others look down upon. In addition to including them, though, he also wants to rescue these young men and their rampant lust from the reproach of others. The young men are “nature’s darlings,” Whitman writes. Nature loves them and their passions as much as any other person or passion. More, you might say, since nature—and the propagation of the human species—depends on these passions.

But Whitman does more than just defend these young men. He identifies with them—and writes poems devoted to “libidinous joys only”—because he too is susceptible to these overwhelming desires. These are “native moments,” and as a part of nature himself, Whitman also experiences them. As he announces in the first line, they come upon him as well. To insist otherwise, Whitman suggests, is to “play a part,” to pretend to be someone he is not, to pretend that he is not occasionally overcome by sexual passion. It is also to “play apart,” to separate, “exile,” himself from his natural companions, male and female. I am, Whitman insists, no better than (and as good as) these young men on their midnight orgies.

Although it may seem tame to us, in its own day the poem—and others like it—could shock. Whitman’s most illustrious reader, Ralph Waldo Emerson, walked with the poet through Boston Common in 1860 and advised him against publishing poems like “Native Moments” in the third edition of Leaves of Grass. Emerson did not mind the poems, but he thought they would scare off readers. Whitman listened thoughtfully and then politely ignored the advice. Poems like “Native Moments” would also get Leaves of Grass literally banned in Boston. In 1882, the Boston district attorney declared the 1881 edition of the book obscene.

In choosing to write about sex, though, Whitman insisted he had no choice at all. After the Boston district attorney banned Leaves of Grass, Whitman published an essay defending himself and his book. “I could not,” he wrote, speaking of Leaves of Grass, which he thought of as one long poem, “construct a poem which declaredly took, as never before, the complete human identity, physical, moral, emotional, and intellectual (giving precedence and compass in a certain sense to the first), nor fulfil that bona fide candor and entirety of treatment which was a part of my purpose, without comprehending this section also.” In other words, if Whitman wanted to write about the complete human identity, he could not ignore something as essential to our identity as sex. “Sex, sex, sex,” Whitman near the end of his life told Horace Traubel, “whether you sing or make a machine, or go to the North Pole, or love your mother, or build a house, or black shoes, or anything—anything at all—it’s sex, sex, sex: sex is the root of it all: sex—the coming together of men and women: sex, sex.”

In this chapter, I listen for what Whitman has to say about sex, the root of it all. I also listen for what he has to say about bodies, the soil of the root of it all, as it were. My hope for reading Whitman so closely, here and throughout this book, is that he can relieve us of our malaise. Unlike death and money, however, where the source of that malaise is obvious enough—we have too much of the former and not enough of the latter—our malaise about sex is less obvious. In his day, Whitman thought his contemporaries suffered from a general unwillingness to speak frankly about sex and bodies. “How people reel,” he told Traubel, “when I say father-stuff and mother-stuff and onanist and bare legs and belly! O God! you might suppose I was citing some diabolical obscenity. Will the world ever get over its own indecencies and stop attributing them to God?” Whitman’s wish would seem to have come true. In many respects, our world has gotten over its own indecencies and its own unwillingness to speak frankly about sex and bodies. Wander into any bookstore and it will doubtless have at least one wall of books devoted to Human Sexuality. And at Penn State, where I teach, students can take any number of courses about the subject, and even minor in Sexuality and Gender Studies. The same is true elsewhere. Or consider popular culture, where what used to be considered indecent is now mined for our entertainment. All told, indecencies would seem to be few and far between.

But too much can be concluded from this superficial flaunting of indecencies. In the world out there, in libraries and classrooms, on television and in best-selling erotic novels, indecencies may seem like a thing of the past. But in our own heads, I believe, and about our own bodies, where it matters, indecencies—things that cannot be said or thought or done—still abound. We may no longer attribute them to God, and they may no longer quite make us reel, but they endure nonetheless. Our sense of shame, that is, is alive and well. (Mine is, anyway, as I discovered in the course of writing this chapter.) Moreover, as Whitman knew, shame keeps us from realizing the splendor of our bodies and the grandeur of our desire. More than anything else, Whitman tries to absolve us of that shame and reconnect us to the miracle of bodies and the torment yet deliciousness of sex. It is a lesson we can still stand to hear.

At the same time, Whitman and other partisans of the sexual revolution may have succeeded all too well. If shame is one source of our malaise, the absence of any shame about our sexuality, what we might call our shamelessness, is doubtless another. By shamelessness, I mean our tendency to treat our bodies—and others’—as machines for the fulfillment of our pleasure. Alas, Whitman occasionally encourages this shamelessness. At his best, though, he reminds us how we might navigate between these two perils: the sin of shame and the equally hazardous sin of shamelessness.

* * *

Here is how I wound up at a strip club in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains.

Before Whitman or anything he wrote can help us, we need to figure out what is wrong with us, and then whether what he has to say is of any use. So, when it comes to sex, what ails us, and what does Whitman propose doing about it? In each of the previous chapters, I am helped along in this search by retracing Whitman’s steps and re-creating what inspired him, hoping not just to understand the poems better but also their contemporary relevance. In the first chapter, I boarded the Brooklyn Ferry, thereby reliving the scene that gave birth to some of Whitman’s profoundest thoughts about death. In the second chapter, I followed Whitman from Brooklyn, where he built houses and took out an ill-advised loan, across the East River, through Wall Street, to Zuccotti Park, where our own generation made its stand against what Whitman called the toss and pallor of moneymaking. A chapter on sex, however, especially one that begins with a poem like “Native Moments,” throws a wrench into this approach. Even if I did not love my wife as completely as I do, I could not, in good conscience, take for my love some prostitute, as Whitman boasts he will do. In addition to being illegal in all but one state, prostitution, to put it mildly, creates certain ethical dilemmas.

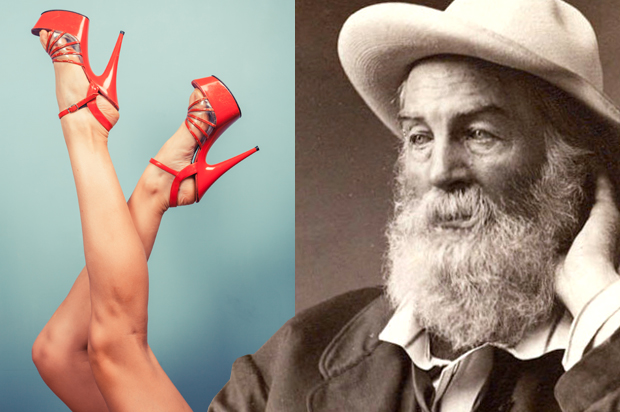

So what to do? How can one share in the midnight orgies of young men without getting arrested or breaking up a marriage? How can we not just read but in some way experience what Whitman has to say about sex? After some thought, it hit me, as if God Himself had revealed it. A strip club! More specifically, the End Zone Show Club in beautiful Port Matilda, Pennsylvania. Its website boasts that it is “Home to Central Pennsylvania’s Hottest Dancers!” Also, that it has a free shuttle from State College. Free shuttle? Sold.

Indeed, where better to dance with the dancers, to drink with the drinkers, to make indecent calls and have them echoed back to me? Where better to find the shunned persons and come forthwith in their midst? Where better to gaze at and celebrate healthy bodies, which Whitman does so often—and encourages us to do—in his poetry? Where better, that is, to understand what Whitman has to say about sex and the body and whether what he has to say is of any use to us today? Strip clubs may be old hat to you, but not me. They retain their air of the illicit and seamy. In short, they make me a little queasy. Except for a compulsory visit to one for a friend’s bachelor’s party about a decade ago, I have mercifully been excused from the places. Something must indeed be wrong with them, then; or, something must be wrong with me for believing that something is wrong with them. In any case, I believe they hold a key to understanding contemporary sexuality. So off I went.

For company on my excursion to the strip club, and for general moral support, I, like Whitman, picked out some low person for my dearest friend, in this case, my real friend Tom. (I have changed his name, though he claims not to care one way or the other.) Tom, it turned out, had more experience with strip clubs than I did. (He had an old girlfriend who was into them.) Together, we made a shabby—though I hoped passable—pack of nature’s darlings.

Tom and I have jobs and families, which makes it difficult to get away to a strip club when the impulse strikes, especially if we also want to get any sleep that night. (I confess that I kept putting it off, too.) As a result, we did not make it to the End Zone until the off-season, so to speak. It was May, classes had ended, and most of the Penn State students and alumni who, apparently, patronize the End Zone had gone home for the summer. After we paid the cover charge, we wandered into a dimly lit though surprisingly clean room about the size of a large lecture hall. Four poles dropped from very high ceilings. Chairs lined the dance pits and walkways. Loud music played.

Unlike many strip clubs, the End Zone makes its money off the cover charge ($20 for men, $10 for women) and not by selling overpriced drinks. In fact, the beer, served on a patio, is free, but no alcohol is allowed in the club proper. On the night we came, about half a dozen men were gathered around a single dancer. As we made our way to the patio bar, the dancer was cradling a man’s head between her breasts. This surprised me—I did not realize the dancers would touch you—but it turned out to be not at all unusual.

After Tom drank a beer, we returned to the club and took our seats, probably farther from the action than was polite. A dancer—perhaps Crista, possibly Felony, it was hard to keep track of their pseudonyms—was sliding around the pole, naked as the day she was born. If that had been the extent of it—naked women dancing at a respectable distance in front of you—I probably would have enjoyed myself more than I did. What straight man, in his heart of hearts, does not like to look at naked women? But it turns out that I do not really know how strip clubs work. Dancers do not stay at a respectable distance from you. Instead, the custom is to put a dollar bill on the ledge in front of you, and, sooner or later, the dancer will make her way over to where you sit and perform for you alone, up close. You are not allowed to touch her, but she is very much allowed to touch you. Or splay in front of you. Or take your dollar bill in unusual ways.

Primed by Whitman’s “Native Moments,” I tried to be for those—and one of those—who believe in the loose delights of the strip club. But that was all talk. In reality, I felt nervous as a zebra in a tiger pit, and I never entirely shed my unease. I had special trouble when the dancers directed their attention to me, personally. I could not look the women in the eyes, even though they look you in the eyes, nor did I feel quite right looking directly at the parts of their body offered up for my inspection. We spend our whole lives carefully covering up those parts. With good reason, we euphemistically refer to them as our privates. Because they are private. No one should have to display them in public, least of all for money, and it seemed wrong to watch the dancers disgrace themselves. The dancers themselves seemed to feel no shame or disgrace, but I could not quite get over the feeling that they should. I could never do what they do, so I thought no one should ever have to, either. Anyway, staring would only make things worse.

Tom and I stayed an hour, maybe longer, mostly out of a sense of scholarly duty. If we had stayed longer things might have gone better, as I grew not exactly more comfortable but perhaps less uncomfortable as the night wore on and I figured out how things worked. Even so, my “native moment” never came upon me, or, if it did, it came and went quickly. My “libidinous joys only” were neither particularly libidinous nor joyful, and the drench of my passions couldn’t have put out a match. Here was life coarse and rank, here were loose delights, and instead of seizing them, as Whitman bid us to, I squirmed. Throughout the night, on a wall-mounted television behind the stage, the Pirates played the Brewers, and from time to time I had to remind myself to watch the dancers and not the game. That was not because I like baseball so much—though the Pirates would make the playoffs that year—but because it seemed less indecent to watch the game than it did to watch the naked woman in front of me humping the stage.

What came between me and my native moments? Why have I not been back to the strip club? I could blame feminism. No one earns an advanced degree in any humanities discipline these days without reading deeply in feminist theory. Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan, Kate Millet, Laura Mulvey, Andrea Dworkin—the list goes on, and none of them would have much good to say about strip clubs, and rightly so. Dworkin, in particular, would have relished the role of killjoy. For Dworkin, pornography, which would include the degrading display of female bodies at a strip club, “creates hostility and aggression toward women, causing both bigotry and sexual abuse.” And you cannot very well enjoy the loose delights of a strip club if, in the back of your mind, you believe that those delights share something with the instincts of the man who beats his wife, the boss who sexually harasses his employee, or the predator who rapes an acquaintance. Feminists, and I consider myself one, will never much relish tucking dollar bills into a stripper’s G-string or, as one patron did, crumbling up dollar bills and throwing them at a woman as she roiled on the checkerboard floor.

It surely did not help to loosen my delights, either, that as a Marxist, I could never quite forget the economic forces guiding the dancers in front of me. Essentially, strippers work for tips, those dollar bills we tuck into their G-strings or crumple up and throw at them. Instead of receiving a wage, many dancers in fact pay the club for the privilege of stripping. To be sure, women (and men) who cut hair oftentimes strike a similar bargain, but somehow stripping seems worse, even if the pay is better. In any case, for Marxists, every dollar tucked into every G-string provides an immediate illustration of the exploitation of labor. I did not ask the question, but I assume that few of the dancers at the End Zone worked there because they felt a calling for taking off their clothes in front of strangers or dancing suggestively in their laps. Nor, I gather, were any of them independently wealthy. Rather, they worked at the End Zone because they needed money, and few jobs, assuming they could even find a job in this economy, paid as well as taking their clothes off for strangers. The owners of the strip club, and indirectly, the patrons of the strip club, including me, all take advantage of their economic insecurity.

Still, I do not think that my feminist and Marxist sympathies can fully explain my lackluster trip to the strip club. Indeed, they probably let me off far too easily. In appealing to them, I can flatter myself into thinking that I am better than the dismal, barbaric patrons who pay for lap dances and ignore the ethical implications of what they do. I do not mean that the feminist or Marxist critiques of strip clubs do not have some truth to them. Only that, if I were being honest with myself, something else put a damper on my outing to the strip club than feminism or Marxism.

Ultimately, I think I did not have fun at the strip club because I did not want to be seen as someone who could have fun at a strip club. Because if you did have fun at a strip club, that would mean that in some sense you were in thrall to your desire, that you had surrendered your reason and your ideals to your lust. To have fun at a strip club would mean admitting that your libido trumps every other card in your hand; that you are more a desiring machine than a thoughtful human being. And among the crowd of educated, liberal, upper-middle class professionals with whom I work, gossip, and organize play dates, you can admit to almost everything else except overwhelming sexual desire. Try it. At the next dinner party, start telling the story of the funny thing that happened to you on the way to the strip club. Or the wild thing you saw on the Internet last night when you were looking at pornography. See if you are invited back.

In retrospect, part of me envies the other men at the strip club, who did not apologize for their lust. By contrast, I could do nothing but apologize for mine, so much so that I apologized it right out of existence. Some of those apologies may have been called for. The feminists and Marxists are right. Some lust does do more harm than good. But so does pretending that you do not lust, ever, or that you have complete control over it. Because if you do have complete control over it, it ceases to be lust at all. And here is where Whitman can help us. He insists, in poem after poem, that an innocent, even healthy form of lust must exist. Perhaps its finest expression is not found in strip clubs, but it must exist somewhere, and it would be surprising if it made no appearance whatsoever at a strip club. Whitman reminds us that we do not want to live in a world without lust, one without libidinous joys, and we certainly do not want to be the sort of person who cannot acknowledge these passions in himself (or, of course, herself).

In other words, those are some of Central Pennsylvania’s Hottest Dancers, and if you cannot admit that, something is wrong.

Excerpted from “In Walt We Trust: How a Queer Socialist Poet Can Save America From Itself” by John Marsh. Copyright © 2015 by John Marsh. Reprinted by arrangement with Monthly Review Press. All rights reserved.