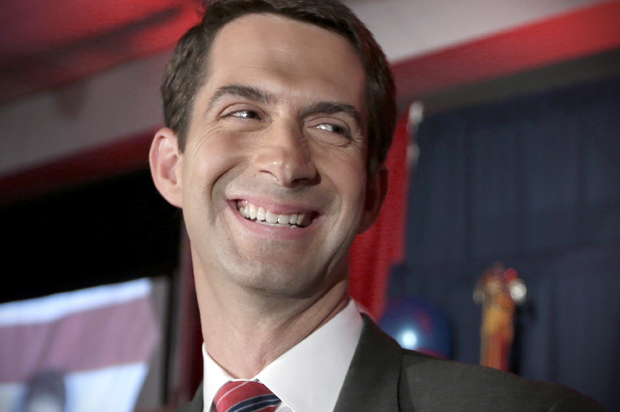

Right-wing Obama hatred and hawkish foreign policy instincts can clash in all sorts of colorful, unexpected ways, but credit to freshman senator and noted piece of work Tom Cotton for this latest twist: neoconservative Neville Chamberlain apologism. If your goal is to describe President Obama as the most naive amateur in the history of foreign policy, that means you have to massage Chamberlain’s reputation ever so slightly. (Another idea would be to find a more applicable analogue to Obama’s Iran policy than Munich 1938, but we can only ask for so much historical flexibility from neoconservatives.)

Cotton fleshes out the line first provided by Sen. Mark Kirk — that the Obama administration is worse than Chamberlain — in a new interview with The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg. Lest anyone think that was just an over-the-top expression of frustration from Kirk, Cotton is proving that they intend to work and expand this argument. It’s not a new strain of thought to suggest that history has given Chamberlain an unnecessarily bum rap, but it’s rare to see a neoconservative like Tom Cotton making it. That’s where hyperbolically anti-Obama posturing brings us today.

“Wait,” a shocked, SHOCKED Jeffrey Goldberg asks Cotton, “this is the 1930s to you?” Is it ever not?

Cotton: It’s unfair to Neville Chamberlain to compare him to Barack Obama, because Neville Chamberlain’s general staff was telling him he couldn’t confront Hitler and even fight to a draw—certainly not defeat the German military—until probably 1941 or 1942. He was operating from a position of weakness. With Iran, we negotiated privately in 2012-2013 from a position of strength, not a position of weakness. The secret negotiations in Oman. This ultimately led to the Joint Plan of Action of November 2013. So we were negotiating from a position of strength—not just inherent military strength of the United States compared to Iran, but also from our strategic position.

Neville Chamberlain operated from a position of weakness and had little choice but to give all the goodies to ol’ Hitler. Obama is operating from a position of strength, and yet he still is giving all the goodies to Hitler, or whatever the new Hitler thing is. Cotton cannot even bring himself to call the preliminary framework a “deal.” He refers to it again and again as a “list of concessions.” When Goldberg tries to bring up just one of the concessions that Iran is making — reducing “their stockpile from 10,000 kilograms to 300 kilograms of highly enriched uranium” — Cotton brushes it aside as, well, we don’t really know the particulars of that and besides, they are lying liars. He similarly dismisses the provision that the underground center at Fordow won’t be enriching uranium. It would have been nice if Goldberg had made him respond to the fact that Iran went into negotiations hoping to maintain a capacity of 50,000 centrifuges and will walk away with 6,000, pending a final agreement.

Sometimes during the course of a long conversation, a politician will forget that he’s staked out a surprising position — defending Neville Chamberlain, for example — and revert back to a contradictory but familiar comfort zone. And sure enough, by the end of the conversation, Cotton is back to trashing Chamberlain for the “dishonor” he showed at Munich:

Cotton: The world probably wishes that Great Britain had rebuilt its defenses and stopped Germany from reoccupying the Rhineland in 1936. Churchill said when Chamberlain came back from Munich, ‘You had a choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor and you will therefore be at war.’ And when President Obama likes to say, ‘It’s this deal or war,’ I would dispute that and say, ‘It’s this deal or a better deal through stronger sanctions and further confrontation with [Iran’s] ambitions and aggression in the region.’ And if it is military action, I would say it’s more like Operation Desert Fox or the tanker war of the 1980s than it is World War II. In the end, I think if we choose to go down the path of this deal, it is likely that we could be facing nuclear war.

Helloooo, final sentence! Because that’s the other thing about this interview, is how Cotton matter-of-factly drops hints about the impending nuclear war to which the Obama administration is setting the world on a path. This is another area where Cotton takes contrasting positions depending on the moment: is Iran a rational actor, or is it not? Is it concerned about self-preservation or is it not?

For the most part Cotton treats Iran as a rational actor. “They react to threats that are severe enough,” he says. To him that means not just preserving sanctions, but the credible threat of military action if Iran doesn’t tear apart its nuclear program. Even though the Obama administration has been saying consistently for years that it will take military action against Iran if it isn’t willing to negotiate, Cotton doesn’t buy this, because Tom Cotton doesn’t like Barack Obama.

But then, because the imagery of a mushroom cloud is too effective to pass up, Cotton reverts to treating Iran like an irrational actor, one intent for religious purposes on nuking Israel (and thus bringing about the instant, retaliatory nuclear destruction of itself.) Here, too, Cotton finds himself defending an unlikely partner — the Soviet Union! — as a convenient contrast to Iran. He argues that “we could always count on the Soviet leadership to be concerned about national survival in a way that I don’t think we can count on a nuclear-armed Iranian leadership to be solely concerned about national survival.” Why not? Well, something about how Iranians say a lot of mean things. “I think it” — Iran obtaining a nuclear bomb — “will probably lead to the detonation of a nuclear device somewhere in the world, if not outright nuclear war.”

The argument of how Iran would act as a nuclear power is hypothetical, because there’s a deal being negotiated right now that would prevent it from becoming a nuclear power, and neither Cotton nor his fellow critics are able to offer a clear explanation for their frequent assertion that this deal ensures Iran gets the bomb. But hey, let’s entertain it anyway. What’s an argument for Iran becoming a nuclear power and this leading to nuclear war? Maybe that Iran going nuclear wouldn’t stop the likes of Tom Cotton and his fellow hawks from pursuing Iranian regime change. That would be a provocative recipe for fireworks, indeed, and it’s something that leads me to believe that the Obama administration is serious when it says that it will do anything to prevent Iran from getting a bomb. Can we be trusted to be the rational actor?