April 14, 1865

good Friday

Hush’d be the camps to-day,

And soldiers let us drape our war-worn weapons,

And each with musing soul retire to celebrate,

Our dear commander’s death

—Walt Whitman

In Charleston, South Carolina, the Stars and Stripes were raised with ceremonial formality over the ruins of Fort Sumter, whose thirty-four-hour bombardment in April 1861 had begun the orgy of slaughter and destruction. Four years to the day after Fort Sumter’s surrender, General Robert Anderson, who in 1861 had lowered the flag in surrender, hoisted the same battered ensign over the fort as Army and Navy guns boisterously consecrated the moment, along with bands and singers. The Reverend Henry Ward Beecher offered gratitude for God’s beneficence. Among those bowing their heads in thanks was the old antebellum agitator, William Lloyd Garrison. “Remember those who have been our enemies,” said the Reverend Doctor R. S. Storrs of Brooklyn, “and turn their hearts from wrath and war, to love and peace.”

In Washington, General Grant and War Secretary Stanton were stopping all military recruiting and the draft, and curtailing military purchases. Indeed, with the surrender of Robert E. Lee’s army, it was a mere matter of time before all hostilities ceased. On the night of April 13, Washingtonians celebrated by illuminating the federal buildings—six thousand lights burned in the Patent Office alone—and strolling along the brightly lit streets.

On the 14th, Lincoln met for two hours with his Cabinet. For the first time, Grant attended, and reconstruction was discussed. Each Southern state presented a unique set of problems that should be addressed separately, Lincoln said. He reiterated his support for Louisiana’s constitution, although he acknowledged that he was disappointed that black suffrage had not been written into it. The president did not want to require the Rebels to pay restitution. As for the Confederacy’s leaders, Lincoln said, “Frighten them out of the country, open the gates, let down the bars, scare them off. Enough lives have been sacrificed. We must extinguish our resentments if we expect harmony and reunion.”

He had had another premonitory dream. The president had had several throughout the war. There was the recent dream in which he was awakened by the sound of sobbing and learned that the catafalque in the White House East Room was his.

In the dream of the night before, he told his Cabinet, he was in “some singular, indescribable vessel,” moving rapidly to an “indefinite shore.” Lincoln said that he had had this same dream before some of the war’s pivotal events: Fort Sumter, Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, Stones River, Vicksburg, and the capture of Wilmington. “We shall, judging from the past, have great news very soon,” Lincoln said. “I think it must be from Sherman. My thoughts are in that direction, as are most of yours.”

But what also might have been on his mind were the murder plots targeting him. They had proliferated the previous fall when it became clear that he was going to be reelected and that the Union would win the war. He once showed newspaperman John Forney a pigeonhole in his office desk where he kept the threatening letters. There were scores of them. “I know I am in danger,” said Lincoln, “but I am not going to worry over threats like this.”

Yet he did worry. On his way to the War Department earlier that day with his bodyguard, William Crook, they passed some drunken men. Lincoln said, “Crook, do you know, I believe there are men who want to take my life?” Almost as though speaking to himself, he added, “And I have no doubt they will do it.” As they continued walking, Lincoln said he had confidence in his bodyguards. “I know no one could do it and escape alive,” he said. “But if it is to be done, it is impossible to prevent it.”

From his first inauguration in March 1861, Lincoln had labored every hour of every day under the burden of waging an increasingly bloody war with an uncertain outcome. Now that he could see the end of it, his mood had become almost buoyant.

On the afternoon of April 14, he took Mary on a carriage ride to the Navy Yard. No aides or bodyguards accompanied them—just as Lincoln liked it. He visited with the sailors and went aboard the monitor Montauk. He was “cheerful—almost joyous,” the first lady observed, and when she remarked to him on this, he replied, “We must both be more cheerful in the future—between the war and the loss of our darling Willie [their eleven-year-old son, who became ill and died in 1862]—we have both been very miserable.”

The Lincolns planned to go that night to Ford’s Theatre to attend the farcical three-act play Our American Cousin, featuring Laura Keene, the renowned actress and Broadway theater owner who now managed a traveling production show; Our American Cousin would close out her two week engagement at Ford’s. The Stantons and the Grants were invited to join the Lincolns in the president’s box, but Mrs. Stanton had told Mrs. Grant that if she did not attend, neither would Mrs. Stanton; she could not stand to be alone with Mrs. Lincoln. Mrs. Grant was in no mood to endure an evening with the difficult Mary Lincoln either; she declined the invitation, saying that she was leaving Washington that night to visit her children at their New Jersey boarding school. Mrs. Stanton promptly sent her regrets, too. Yet, the notice that theater manager James Ford had placed in the afternoon newspapers announced that Grant, the Lincolns, “and other distinguished personages” would be present.

Ward Lamon, Lincoln’s self-appointed bodyguard, was not going. Before leaving for Richmond, Lamon had warned the president against going out at night. War Secretary Stanton also urged Lincoln not to mingle with the theater crowd. It was an unusually dangerous night for the president to be abroad, Stanton said, because of the newspaper notice that both he and Grant would be in the president’s box, where they would be in plain sight.

* * *

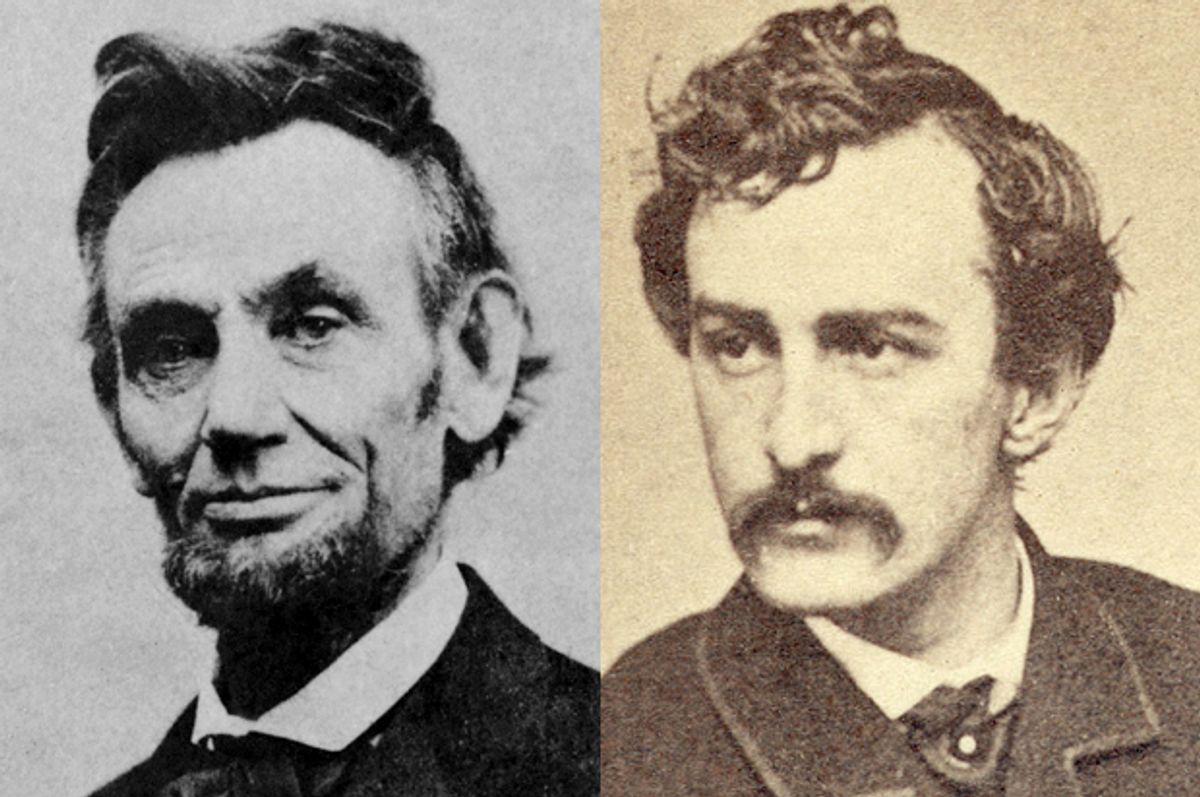

John Wilkes Booth, twenty-six years old and darkly handsome, was the youngest member of America’s foremost theatrical family. His father, the famous English-born stage actor Junius Brutus Booth, had become an instant sensation after immigrating to the United States. When Junius died in 1852, Edwin Booth, one of John’s two older brothers, assumed the family patriarchy and became the nation’s best-known tragedian. In March 1864, Edwin Booth gave a command performance for Lincoln in Washington to celebrate the third anniversary of his inauguration.

Although a well-known leading actor in his own right, John did not have Edwin’s prodigious talents, and he never matched his brother’s achievements on the stage. Before the war Edwin had decided that rather than compete for audiences against his brother John, he would perform on Northern stages, while John would tour the South, a less lucrative territory.

Living in the South, John became infatuated with the region and its culture, and as war approached, he enthusiastically supported the Confederacy. But when the shooting war began, John moved North, although his passion for the Confederacy intensified—to the extent that his ardent Unionist brother Edwin expelled John from his home after a violent quarrel over the war.

By late 1864 John was telling his friends that he had handsomely profited from the oil wells he owned in Pennsylvania and might retire from the stage. But oil wasn’t absorbing his energies so much as his growing radicalism on behalf of the Confederacy. When Lincoln’s reelection became fact, all but dooming the South to defeat, Booth was spurred to act.

Radical measures were now being openly proposed in the South. The Richmond Whig on November 1 even raised the subject of tyrannicide: “Some brave democrat, devoting himself for his country, would surely with bullet or pontard [sic] rid the world of that grotesquely horrible Frankenstein.” The newspaper, however, shrank from openly advocating Lincoln’s assassination. “Not what we desire to see Abraham Lincoln put out of the way either by that method or any other,” the Whig wrote. “He suits us exactly as the ruler of an enemy’s country; and our suggestion is altogether in the interest of any of his unfortunate subjects who may still possess the spirit of men and of freemen.”

While Southerners despaired about the future, the romantic Booth, who had spent the war in comfort in the North, perversely resolved to share “the last ditch” with his Southern brethren. In November, he met in Montreal with high-ranking Confederate spies and committed himself to a far-fetched plot to kidnap President Lincoln. The scheme was concocted with the knowledge of Jefferson Davis, who authorized gold to be sent to one of the ringleaders, Thomas Conrad. The Rebel agents gave Booth money to put the plan into action.

In a letter to his mother Mary, Booth melodramatically announced that the time had come for him to perform “a noble duty for the sake of liberty and humanity due to my Country. . . . For four years I have lived a slave in the north. . . . Not daring to express my thoughts or sentiments, even in my own home. Constantly hearing every principle, dear to my heart, denounced as treasonable. . . . And knowing the vile and savage acts committed on my countrymen their wives & helpless children, that I have cursed my willful idleness. . . . For four years I have borne it mostly for your dear sake . . . but it seems that uncontrollable fate, moving me for its ends, takes me from you, dear Mother, to do what work I can for a poor oppressed downtrodden people.”

In December, Booth was busy enlisting potential allies in pro-Confederate southern Maryland for his plot, and meeting with a small group at various Washington saloons and Mary Surratt’s boarding house. Booth intended to seize the president when he was riding alone, as he often did, to the Soldiers’ Home outside Washington and smuggle him through southern Maryland and down to Richmond. With the money he had received in Montreal, Booth bought two Spencer repeating rifles, six revolvers, two Bowie knives, handcuffs, and ammunition. He purchased a boat and found an oarsman at Port Tobacco to take him across the Potomac River to Virginia when the time came.

But Booth was uncomfortable with the idea of kidnapping the president in a rural area; he was far more at home in the Washington theaters than in the countryside. Booth revised his plan—he would seize the president while he was attending a play, rather than while riding outside Washington. Booth’s coconspirators objected, but could not dissuade him.

Booth shadowed Lincoln for weeks, and even had a seat at the president’s swearing-in on March 4, thanks to his secret fiancée, Lucy Hale, a New Hampshire senator’s daughter, who obtained a ticket for him. In early April, the Confederacy’s collapse convinced Booth that kidnapping the president would not be enough; he resolved to murder Lincoln. Booth later boasted to a friend, “What an excellent chance I had to kill the president, if I had wished on Inauguration Day! I was on the stand, as close to him nearly as I am to you.” The shocked friend asked Booth why he wanted to kill the president. “I could live in history,” replied Booth.

On April 11, he was at the front of the crowd when Lincoln delivered his reconstruction speech at the White House. When the president advocated black voting rights Booth reportedly said, “That means n—r citizenship. Now, by God, I’ll put him through.”

Booth decided to also kill William Seward, and assigned the mission to a hulking, twenty-year-old Confederate combat veteran named Lewis Powell, whose service included more than a year with John Mosby’s famed Rangers. It was curious that Booth targeted the secretary of state instead of War Secretary Stanton. But Booth and others like him had nursed a profound hatred of Seward for years because his views were so diametrically opposed to theirs. Moreover, they believed that Seward, because of his strong convictions, would pose a greater threat to their interests than any other Cabinet member if Lincoln were killed.

During the day on April 14, Booth slipped into Ford’s Theatre, whose layout he knew intimately, and drilled a peephole in the door that opened directly into the presidential box. A narrow hallway and a second, outer door separated the box from the balcony corridor. Booth armed himself with a .44-caliber derringer and a dagger and waited for nighttime.

He attempted to explain himself in a rambling letter “To the Editors of the National Intelligencer.” “Baffled and disappointed” by previous efforts to advance “my object”—evidently the kidnapping plot—“the hour has come when I must change my plan,” he wrote, to “a bolder and more perilous one. . . . If the South is to be aided it must be done quickly. It may already be too late.” He compared himself to Brutus, who murdered Caesar when his power “menaced the liberties of the people. . . . The stroke of his dagger was guided by his love of Rome. It was the spirit and ambition of Caesar that he struck at.”

“Many, I know—the vulgar herd—will blame me for what I am about to do, but posterity, I am sure, will justify me,” wrote Booth. “Right or wrong, God judge me, not man. Be my motive good or bad, of one thing I am sure, the lasting condemnation of the North.”

* * *

The Lincolns arrived at Ford’s Theatre at 9 p.m. Ward Lamon and William Crook, the president’s usual bodyguards, were absent. Instead, a metropolitan policeman named John Parker accompanied the president and first lady. Concerned about the light security, Stanton assigned Major Henry Rathbone to sit with the Lincolns. Rathbone escorted his fiancée, Clara Harris, daughter of New York Senator Ira Harris.

The Lincolns, Rathbone, and Harris settled into their seats in the box. The play had already begun, but a murmur ran through the theater when the audience saw the president and first lady.

Parker sat down in a chair outside the door where Booth had made the peephole, but he neither noticed the peephole nor remained in place for long. A poorer bodyguard than Parker would have been hard to find in the metropolitan police department. He had been disciplined numerous times—for using disrespectful language, for having lived five weeks in a house of prostitution, and for sleeping on the job. On this night, Parker left his post outside the presidential box, where he could hear but not see the actors. He slipped into an aisle seat in the audience where he could watch the play. Later, the delinquent bodyguard went outside for a drink.

At the beginning of Act Three Booth entered the narrow hallway, barred the balcony door behind him, and peered through the peephole at Lincoln, who was sitting in a rocking chair. Booth moved quickly, bursting into the box with his derringer in his right hand and a dagger in his left, and shot the president behind his left ear from less than five feet away.

Major Rathbone sprang from his seat and grappled with the slender, dark-haired assailant dressed in black. During the struggle, Booth dropped his pistol, slithered out of Rathbone’s grasp, and lunged at him with the dagger, slicing his left bicep when Rathbone threw up his arm protectively.

Booth agilely leaped to the railing at the front of the box, and as Booth began to jump to the Stage ten feet below, Rathbone managed to grab a handful of Booth’s jacket, throwing him off balance and causing his spur to catch on one of the flags draped over the front of the box. Booth landed awkwardly on the stage, injuring his left leg. In the glare of the footlights Booth thrust his long dagger above his head and cried, “Sic Semper Tyrannis”—the state of Virginia’s motto, meaning “thus always to tyrants.” Many of the theatergoers instantly recognized the famous actor before he darted from the stage, slashing the air in front of him to clear a path. He ran out the theater back door to an alley and galloped off on a mare waiting for him there.

* * *

From the president’s box came a piercing scream that broke the stunned silence that had fallen over the open-mouthed audience. Someone shouted, “Our president! Our president is shot!” Pandemonium erupted, with men crying, “Kill the murderer! Shoot him! Catch him! Stop that man!” Someone bellowed, “Burn the theater!” A chant arose, “Booth! Booth! Booth!” Angry men smashed seats, and the crowd surged toward the stage, pinning people against the orchestra.

Laura Keene stepped to the front of the stage and shouted to the audience for order. Then someone in the president’s box called for her to bring a pitcher of water and a glass. Keene found them backstage and made her way to the box. There she saw the president lying on the floor. He appeared dead, but Captain Charles Leale, a twenty-three-year-old Army surgeon, and two other surgeons were trying to resuscitate him. Lincoln was bleeding from the entry wound, and his right eye bulged where the bullet had lodged behind it. Keene sat on the floor and cradled the president’s head in her lap, with her palms on either side of his face. Keene’s clothing became crimson stained.

Leale rounded up volunteers to carry the president out of the theater. Lincoln’s carriage was readied to take him to the White House, but Leale said the president could not survive the bumpy six-block ride and should be taken to the nearest private home instead. Lincoln was carried across the street to a small bedroom in the rear of William Petersen’s four-story brick boarding house.

While Booth had been closing in on Lincoln, Lewis Powell was arriving at the door of William Seward’s home, where the secretary of state was in bed recovering from his carriage accident injuries. Powell told the doorman, William Bell, that he was delivering medicine. When Bell refused to admit him, Powell brushed past him and bolted up the stairs to the third floor, where Seward’s son Frederick confronted him. Powell tried to shoot him, but the pistol jammed, and so he savagely beat the young man with the pistol butt until the gun fell to pieces. Bursting into the room with the wreck of a revolver in one hand and a knife in the other, Powell punched Seward’s daughter Fanny, pinned Seward to his bed with one hand, and began slashing him in the face and neck with the knife.

Fanny screamed, “Murder!” bringing a male nurse and Seward’s other son, Augustus. Powell flung both of them aside and ran down the stairs. On his way out the front door Powell stabbed a State Department messenger in the back before mounting his horse and riding away.

* * *

At 10:30 p.m., Navy Secretary Gideon Welles was awakened from a sound sleep and plunged into the middle of a nightmare: Lincoln had been shot and Seward attacked in his home. Welles quickly dressed and walked to Seward’s home just across the square. Stanton arrived in a carriage about the same time. They found the sixty-three-year-old secretary of state in a “bed saturated with blood,” a cloth covering part of his head and eyes. Frederick was in worse condition, “weltering in his own gore.”

Although everyone urged them not to, the two Cabinet members got into Stanton’s carriage and went directly to the Peterson boarding house, where Lincoln lay dying. A doctor told Welles that Lincoln “was dead to all intents,” but might cling to life for a few more hours. Welles and Stanton entered a bedroom where the president had been laid diagonally across a bed that was too short for him. Part of Lincoln’s face was discolored, and his right eye was swollen. Without clothing Lincoln was impressive, Welles thought, with his large rail-splitter’s arms, remarkable for a man of his thinness.

The rest of the Cabinet, Seward excepted, piled into the small bedroom, and it became uncomfortably warm and overcrowded. Every hour during the long night, wrote Welles, Mrs. Lincoln would come to her husband’s bedside “with lamentations and tears.”

Outside, the large crowd that had gathered in the street could hear Mrs. Lincoln’s hysterical shrieks. While sitting with her husband, she at one point cried out in anguish, “Kill me! Kill me! Kill me, too! Shoot me, too!”

In another room Stanton organized a manhunt for Lincoln’s and Seward’s assailants, barking orders to subordinates and couriers. He asked New York City’s police chief to send down three or four of his best detectives. Stanton stopped all rail and ship traffic in and out of Washington and Baltimore and ordered troops to seal the roads into those cities. He and Attorney General James Speed also interviewed witnesses, whose accounts were taken down by a shorthand reporter. The war secretary shuttled between his provisional headquarters and the bedroom where Lincoln lay dying.

“He lay with his head on [the] pillow, and his eyes, all bloodshot almost protruding from their sockets,” wrote the boarding house owner’s son, fifteen-year-old Fred Petersen. “His jaw had fallen down upon his breast, showing his teeth.” Each breath made a “dismal, mourning, moaning” sound.

Ulysses and Julia Grant were in a Philadelphia restaurant for a late evening meal as they waited to cross the Delaware River on a ferry to New Jersey when three telegrams were delivered to their table. Grant blanched as he read them. Julia asked what was wrong. “Something very serious has happened,” Grant said. “Do not exclaim. Be quiet and I will tell you. The President has been assassinated at the theater, and I must go back at once.” Later, Grant was heard to mutter, “This is the darkest day of my life.”

Stanton also telegraphed Sherman, warning him to be on guard because of “evidence that an assassin is also on your track.” General Henry Halleck, the Army chief of staff, sent Sherman a description of the would-be killer that was so vague that it could have matched thousands of men in Sherman’s own army. The assassin’s name was Clark, said Halleck.

At 7:22 a.m. on April 15, Lincoln died. Surgeon General Joseph Barnes folded Lincoln’s hands across his chest and rose from his bedside. “He is gone,” Barnes said.

The Cabinet moved to a back parlor, officially convened, and signed a letter prepared by Attorney General Speed to be delivered to Vice President Andrew Johnson. The letter informed him of Lincoln’s death and his accession to the presidency. Two other men—John Tyler and Millard Fillmore—had become president when the chief executive died of natural causes; Johnson was the first vice president to succeed a murdered president. Chief Justice Salmon Chase swore him into office at 11 a.m. at the Kirkwood House hotel.

* * *

Vengeful mobs materialized in Washington early that morning, and one of them converged on the Old Capitol Prison after hearing rumors that its four hundred Confederate prisoners were at that moment escaping. They were not. “Hang ’em! Shoot ’em! Burn ’em!” the men cried, preparing ropes to carry out their spurious sentence on the Rebels, who neither knew that Lincoln was dead, nor that their lives were in peril. Congressman Green Smith of Kentucky and some friends barred the mob’s way. While Smith pleaded with the crowd, others ran for help. Union soldiers arrived in time to prevent a massacre.

But the public mourning was mostly peaceful. “Everywhere, on the most pretentious residences and on the humblest hovels, were black badges of grief,” wrote newspaper correspondent Noah Brooks of the observances in Washington. The weather matched the city’s funereal mood. “The wind sighed mournfully through the streets crowded with sad-faced people, and broad folds of funeral drapery flapped heavily in the wind over the decorations of the day before,” Brooks wrote.

Julia Ward Howe, who wrote the lyrics for “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” set to the tune of “John Brown’s Body,” learned of Lincoln’s death while at her Beacon Hill home in Boston. “Nothing has happened that has given me as much personal pain as this event,” she wrote. A reporter in Springfield, Illinois, wrote that Lincoln’s hometown was bowed down in sorrow as if “the Death Angel had taken a member from each family.”

Lincoln’s death deeply upset Frederick Douglass, who described the assassination as both “a personal as well as national calamity; on account of the race to which I belong and the deep interest which that good man ever took in its elevation.” Brooks summarized Lincoln’s achievements in moving words, “A martyr to the national cause, his monument will be a nation saved, a race delivered, and his memory shall be cherished wherever Liberty hath a home.”

New York diarist George Templeton Strong wrote after learning of Lincoln’s death, “There is a profound, awe-stricken feeling that we are, as it were, in the immediate presence of a fearful, gigantic crime, such as has not been committed in our day and can hardly be matched in history.”

Two days later he added, “Death had suddenly opened the eyes of the people (and I think of the world) to the fact that a hero has been holding high place among them for four years.”

The Union Army grieved—and thirsted for vengeance. “Everyone seems to feel as though his Father had been assassinated and all they [long] for was only another 6th of April [Sailor’s Creek] to Avenge his death on the rebel Army,” Sergeant John Hartwell wrote to his wife.

Fearing that his men would run amok in nearby Farmville, Virginia, Joshua Chamberlain posted a double guard around his brigades’ bivouac outside the town. His men, he said, “could be trusted to bear any blow but this . . . he had taken deep hold on the soldier’s heart, stirring its many chords.” Later, Chamberlain and two other generals went to see their commander, General George Meade. “We found him sad—very sad.”

Most Southern military and civilian leaders experienced “a shudder of horror at the heinousness of the act, and at the thought of its possible consequences.” But others received the news with bitter joy, regarding Lincoln’s death “as a sort of retributive justice,” wrote John Wise, the son of General Henry Wise and a courier for Jefferson Davis. “Lincoln incarnated to us the idea of oppression and conquest. We had seen his face over the coffins of our brothers and relatives and friends, in the flames of Richmond, in the disaster at Appomattox,” he wrote. “We greeted his death in a spirit of reckless hate, and hailed it as bringing agony and bitterness to those who were the cause of our own agony and bitterness.”

Some of Lincoln’s detractors in the North made the mistake of blurting out their approval of the assassination in front of grief-stricken countrymen. James Hall was sentenced to two years in prison for loudly declaring in a Baltimore saloon, “John Wilkes Booth done right.” Samuel Peacock got thirty days’ hard labor for saying, “He ought to have been killed long ago.” There was even ill-considered jubilation in the Union Army’s ranks; nearly seventy Union soldiers and sailors were prosecuted for expressing satisfaction with the assassination.

In San Francisco, mobs destroyed the offices of two anti-Lincoln newspapers. A citizens’ group ordered the editor of the Westminster, Maryland, Democrat, Joseph Shaw, to leave town. He did, but then returned; he was killed. Laura Keene and her theatrical company were repeatedly arrested while traveling to Cincinnati, despite having been cleared in Washington of any connection to the assassination.

A rumor circulated in Washington that Booth was seen among Confederate prisoners being marched through the streets, and a mob attacked the prisoners, guarded by Union troops. Several people were wounded in the melee, including some of the guards, before the crowd was satisfied that Booth was not there.

It was unsurprising that there were such outbursts, with revenge being preached from church pulpits across the country. In Auburn, New York, the Reverend Henry Fowler said, “Each American seemed called to avenge the blood. . . . The President, living teaches us mercy, and we listen with consent to amnesty and re-construction; but the President murdered, teaches us retribution, and we swear above his open grave, extermination against treason and its plotters.” Mercy for the penitent but not for “those who will murder from behind,” added Fowler. “I call upon government to unsheathe the sword of justice, and I do it in the name of moral law and of Infinite Righteousness.”

* * *

On April 17, Lincoln’s body was placed in a mahogany, lead-lined coffin and taken to the White House East Room, where it lay in state. An honor guard of Army and Navy officers stood watch over the murdered president day and night, while an estimated thirty thousand people passed through the black-draped room to view the remains.

On the 19th, the day of Lincoln’s funeral, the Union Army suspended operations everywhere. Officers and men wore black crepe on their left arms, and the headquarters’ tents and unit colors also bore badges of mourning. General Chamberlain’s men formed a square and listened to an address by the senior chaplain, Father Egan Irish.

In the White House East Room, the Reverend Doctor Phineas Gurley, Lincoln’s pastor, delivered the homily to six hundred dignitaries. “God be praised that our fallen chief lived long enough to see the day dawn and the day star of joy and peace arise upon the union. He saw it and he was glad,” said Gurley. In a closing prayer, the Reverend Doctor E. H. Gray, the chaplain of the US Senate, said, “God of justice, and avenger of the nation’s wrong, let the work of treason cease, and let the guilty author of this horrible crime be arrested and brought to justice.”

There was no music, underscoring the ceremony’s solemnity. Members of Congress, Grant, General Henry Halleck, and Admiral David Farragut were honorary pallbearers. The Supreme Court was there, along with many governors and the new president, Andrew Johnson. Undone by her husband’s death, Mrs. Lincoln did not attend; she had still not left her room and was turning away nearly all visitors. Grant sat apart from the others at the head of the catafalque. Tears ran down his cheeks during the service.

The casket was carried outside and placed in a hearse, around which crowded thousands of people. Throughout the city, cannons boomed, bells tolled, and bands played dirges during the hearse’s journey down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol. Grim spectators, up to sixty thousand of them, thickly lined the road to glimpse the president’s casket, the riderless horse, and the flag, torn by the assassin’s spur, which had adorned the president’s box at Ford’s Theatre. The solemn pageant passed Seward’s home, and the injured secretary of state sat up in bed to see it. The coffin was placed in the Capitol rotunda on public display until the next evening. Twenty-five thousand people stood in line to pay their respects.

On the evening of the 20th, the president’s remains began their sixteen-hundred-mile, meandering rail journey that would end in Springfield, Illinois. Making the trip with Lincoln’s body was the exhumed coffin of his son Willie. Mrs. Lincoln remained at the White House, “more dead than alive, shattered and broken by the horrors of that dreadful night,” wrote Noah Brooks.

Over twelve days, Lincoln’s funeral train traveled to ten cities, including Philadelphia, New York, Albany, Cleveland, Columbus, Indianapolis, Chicago, and, finally, Springfield. Between Washington and Springfield an estimated 7 million people lined the train’s route. About 300,000 people filled Philadelphia’s streets to view the coffin at Independence Hall. Squashed and trampled, Philadelphians waited up to eight hours to glimpse their dead president. In New York up to 120,000 people passed Lincoln’s remains at City Hall; many women tried to kiss the dead president on the lips. Nearly a million people watched the procession wend its way through New York’s city streets to the railroad station. From a second-floor window of a mansion along the route, the two young sons of Cornelius Roosevelt observed the austere pageant: six-year-old Theodore Roosevelt, the future president, and his younger brother, Elliott, the future father of Eleanor Roosevelt, who would become the wife of another Roosevelt president.

Early May 3, Lincoln’s remains reached Springfield, from which he had set out for Washington in February 1861 and to which he had not returned until now, in death. The coffin was taken to the state Capitol, where Lincoln had delivered his “House Divided” speech, and was displayed in the rotunda for the next twenty-four hours. About seventy-five thousand people filed past the dead president.

The procession to Oak Ridge Cemetery began at 11:30 a.m. on May 4. Lincoln was buried at noon, Willie reinterred beside him. At the graveside services, as thousands of people strained to hear the words, one of the three officiating ministers read Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address as a testament to his principles and hopes for the nation.

Excerpted from "Their Last Full Measure: The Final Days of the Civil War" by Joseph Wheelan. Excerpted by arrangement with Da Capo Press, a member of the Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2015.

Shares