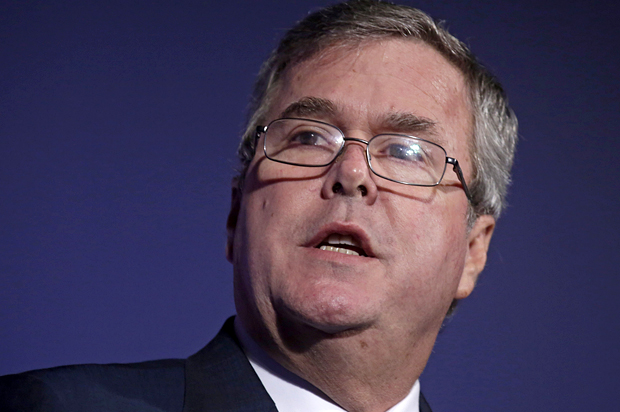

The last major federal campaign finance regulation on the books has been swiss-cheesed into a joke, so you can’t really blame Jeb Bush for laughing at it.

That would be the limit on individual donations to political campaigns, set for this cycle at $5,400 per candidate ($2,700 for the primary, $2,700 for the general.) Bush is making the long-prophecied, post-Citizens United move to “outsource” most of his presidential campaign to a super PAC, Right to Rise. Bush is quite obviously running for president, but all he has to do to continue coordinating with his super PAC in the pursuit of unlimited donations is claim that he’s “seriously considering the possibility of running for president.” This should not be legal but it is, due to the aforementioned joke that is campaign finance regulation in this country.

A common-sense argument to make after Bush’s decision is that his feigned agnosticism about whether he’ll run and his “outsourcing” strategy violate the spirit of the law. The FEC should tighten its rules for determining what counts as candidate activity — hiring tons of staffers for Iowa and New Hampshire seems like a reasonable giveaway! — and restrict super PACs from absorbing a laundry list of traditional campaign duties.

This line of thought — that if there’s an easily loopholed regulation out there, then the regulation should be tightened to eliminates those loopholes — does not appeal to the conservative jurists that comprise the Supreme Court majority. When it comes to campaign finance, they’re far more receptive to Republican legal arguments in the other direction: that if there’s an easily loopholed regulation out there, it’s best to just strike the regulation entirely.

Election law expert Rick Hasen, writing at Slate, lays out the opening that Bush’s play provides for Republican lawyers:

By signaling that Right to Rise is his campaign arm, Jeb Bush has broken down the wall between his super PAC and his campaign committee in the eyes of donors. Preventing coordination and preserving independence was one of the last walls that were left.

The next step will be simply handing $1 million checks to candidates. Right now that’s still illegal, but campaign finance opponents will challenge those candidate contribution limits as ineffective since (the Bush campaign will show) super PACs can serve almost the same purpose. Indeed, campaign lawyer Jim Bopp (the brains behind the Citizens United lawsuit) signaled as much this week, arguing that the way to take unaccountable money out of politics is to let individuals give whatever they want directly to candidates.

This would be hilarious if it weren’t so likely to succeed at the highest level of our third branch of government. Jeb Bush will flout the spirit of the law, and then lawyers like Jim Bopp will go before the courts and say, see how easy it is to flout this law? We might as well get rid of it, because then at least there’s some accountability with the money flowing directly to the candidate. Rather than looking back at the precedents they set forth in Citizens United, John Roberts and company will very seriously nod their heads in agreement as attendees at a nonsense David Brooks speech to the Aspen Ideas Festival might.

The justices in the Citizens United majority set the country’s campaign finance laws on a slippery slope towards non-existence. Now they’re just riding it out and ignoring any impulse towards self-reflection along the way.

In last year’s McCutcheon v. FEC decision, which struck down aggregate caps on contributions to campaigns and parties per donor, the Court seemed to acknowledge that Citizens United had sent a flood of money into super PACs. Instead of rethinking what it had wrought, the Court instead pressed further: since there’s all this money running into politics anyway, thanks to us, we might as well allow donors to channel that money back through official channels. The lawyers for McCutcheon argued that parties and campaigns were being squeezed out by super PACs, and the resolution to that should be to strike down limits on parties on campaigns so they could stay competitive — not to revisit the case law that gave birth to super PACs in the first place.

The Court’s conservative majority broke longstanding precedent to unleash a tidal wave of money into political campaigns in Citizens United. Now, with more than a little bit of chutzpah, it sees its role as a ethical one, ensuring that all that cash isn’t eliminated but shepherded through the most accountable channels. There are no aggregate caps for donations to independent-expenditure groups, it reasoned in McCutcheon, so it’s only fair that there not be any aggregate caps for donations to campaigns and parties. Jeb Bush is effectively soliciting unlimited donations for his campaign by running it through a super PAC, a chin-stroking John Roberts will soon reason, so he might as well be able to solicit them directly for his official campaign.

This is all inevitable so long as Justices Roberts, Kennedy and the rest don’t view donations as “corrupting” to the political process. And that precedent has been set. In McCutcheon, Roberts showed his cards, arguing that the legal standard for evidence of corruption is “quid pro quo corruption.” Basically, you need to secure a photo of a robber baron handing a politician a sack of cash and the politician handing the robber baron some sort of contract in return. To me, and I’d suppose many others, the idea of the five leading Republican presidential candidates flying out to “audition” for Charles Koch and the unlimited funds he could wire to their super PACs is evidence enough that our political process has been corrupted. But that’s still too discreet for the standard Roberts has set. So what’s the harm in allowing Charles Koch to wire those unlimited funds directly to their campaigns instead?

Expect 2016 to be the last presidential election in which candidates, at least on paper, are restricted from receiving unlimited donations to their official campaigns.