For quite a while now, a running theme of public commentary on American politics has been to fret over its persistent and escalating partisanship.

Yet despite Americans’ reputation for friendliness and their professed fondness for compromise and moderation, the reality of U.S. politics can often make you wonder if Clausewitz had it wrong when he called war “the continuation of politics by other means.” Turn on cable news, read a news website’s comment thread, or bring up a political issue on Facebook and you’re liable to feel that, in truth, it’s the other way around.

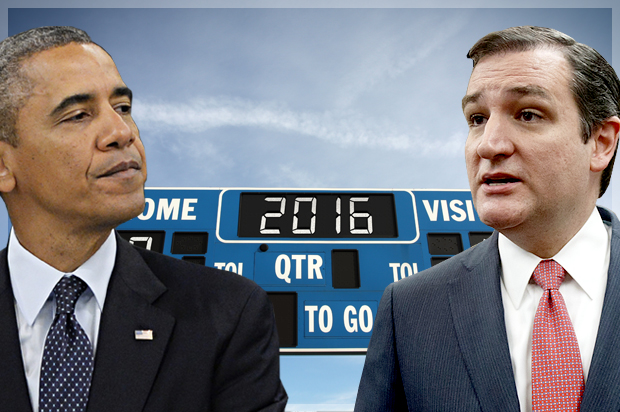

As President Obama has understood so well throughout his career, there’s an intense yearning in America for a leader who will stop all the bickering and make everyone get along. But as President Obama has learned so painfully throughout his time in the White House, it appears to be impossible to translate those generally heartfelt sentiments from theory into practice. The question is why.

Of course, there’s almost certainly no one, single answer. Some prefer to blame a failure of political leadership; others are more comfortable with structural explanations. However, what if the problem isn’t “the folks in Washington” or “the system”? What if one of the problems is, well, us? What if, in a sense, we really are the ones we’ve been waiting for — but not to lead so much as go away and shut up?

That is one of the awkward implications of research from the University of Kansas’ Patrick Miller and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Pamela Johnston Conover, whose new study on partisanship and policy was covered by Salon earlier this month. According to the study, the voters most likely to show up and vote also tend to be the ones more likely to view politics through a zero-sum, hostile and uncivil lens. To them, politics may not be war, but it’s something close to it — sports.

Recently, Salon spoke over the phone with Professer Miller about the reactions to the study, the mind-set of these partisan voters and what implications his work may hold for political science and American politics in general. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

Now that your work has gotten a lot of media attention, have you seen any misconceptions arising that you’d like to correct?

If I have a quibble with the coverage, it’s depicting politics as if everyone out there who calls themselves a Republican or a Democrat really buys into this hostile, us-vs.-them mentality, where winning is the most important thing and policy is really a secondary goal. What we’re trying to show in the research is that that kind of mentality is there for a lot of average partisans — too many, from our perspective — but in speaking to political scientists and journalists, we’re trying to maybe convince them to not be as generous to average citizens in what motivates the citizens to participate in politics.

We oftentimes think of citizens as very calculating and rational in thinking about issue positions and voting for the party that’s closer to them. That reflects some citizens but, I would argue, not most. There’s this entire mentality out there of being intensely committed to a party and rooting for that party, oftentimes for the symbolism of it; and that’s a very compelling motivation for a lot of citizens. But there really are lots of different mentalities.

How are voters supposed to act, according to the conventional wisdom of political science?

It’s changed a lot, actually. Back before we had surveys that really looked at politics in a systematic way, social scientists and even popular culture were very generous toward the average citizen. Before we had the data to prove otherwise, we really had a popular notion that average Americans were informed, attentive, they cared, they were interested in politics, they had strong issue positions, and that they were these really politically sophisticated animals, who then brought that to their own politics.

I think when we first started to study citizens, we got disabused of those notions pretty quickly. There are some voters like that, but the average American — and this is true of the average citizen of other democracies as well — doesn’t care that much and isn’t that informed. They pay attention to politics very little, mostly at election time, and what is strongly motivating them in terms of issue preferences and voting is their loyalty to their parties … We get it from our parents; we learn that we are Republicans or Democrats before we learn that we should be liberals or conservatives, pro-life or pro-choice, etc.

How does the primacy of party identity interact with the recent decline of partisan affiliation, with more Americans than ever describing themselves as independents?

That ebbs and flows over time. Political scientists realized about 30 years ago that most people who call themselves independents are not actually independent. In fact, we call them “closet partisans” (although that’s probably not the most politically correct term).

For these voters, there’s something about a party label that’s a little less appealing to them. Saying that you’re a partisan, for many Americans — but not all — implies maybe blind attachment; it’s maybe a bit of an uncomfortable label. Maybe it’s a product of the times: When a particular party’s brand isn’t doing so well, some of that party’s voters will call themselves independents. Around the end of the Bush era, fewer people were calling themselves Republicans and more people were calling themselves independents but they were just as conservative and voted just as Republican; it was just a label change.

What makes the kind of rigid, absolutist partisans different from other voters?

They tend to be more knowledgeable about politics. This is an interesting double-edged sword about political knowledge that we see reflected in some other studies: people who are more informed about politics are actually more vicious partisans. The kind of citizen for whom politics is interesting, is compelling, they pay attention, they learn a lot, and it reinforces their attachment to their parties, whereas a less-knowledgeable citizen has less of these undesirable attitudes we talk about in our research.

These people also tend to be older, for example, and that makes sense to us; if you’re born into a party and you live through election after election after election, people’s party attachments can harden over time. By the time you get to be an older person, you’ve just lived that reality of constant competition … for a long time, and you’re more likely to think about politics as “my group vs. their group” and beating them at “the game.”

Do these hyper-partisans have ways of justifying their “undesirable attitudes”? Or do they think their opponents are so self-evidently pernicious that it’s not necessary?

For some voters, that us-vs.-them mentality might arise out of issues, especially issues that have been on the agenda for a very long time; contentious issues, especially ones that can easily be moralized.

Take an issue like abortion, for example, where there are some very intensely committed people on both sides of the issue. If that’s a constant source of conflict between the parties … it becomes about the sense that other people have different values and are immoral. It can go beyond abortion or same-sex marriage and just translate into a sense of difference and incompatibility.

In a politically polarized era like today’s, we’re constantly getting the message that the parties aren’t just different but they are dramatically and diametrically opposed, and that they are just fundamentally different in terms of what they believe, what they value, and whom they favor. What comes across in our research is that no matter how you arrive at this sports team, us-vs.-them mentality, once you do, it’s an independent motivating phenomenon.

Jonathan Bernstein of Bloomberg View recently argued that Sen. Marco Rubio’s immigration heresies wouldn’t necessarily undo him as long as he was able to convince GOP primary voters that he’s still one of them and is on their side. Does that sound right to you?

I think so. If we think about general elections, they’re incredibly driven by party. If you look back at the 2012 election, over 90 percent of Republicans and over 90 percent of Democrats just voted straight-ticket for their party. Whoever their party nominates, that’s who they’re going to support, even if they don’t necessarily like that candidate … But when we go to a primary, party is taken off the table.

Look at the Republican field right now; how do you even begin to distinguish between these candidates? I think what you see is that a lot of them will talk about the identity, the symbolism, the label. Everybody wants to be the “Reagan conservative,” right? “Reagan” and “conservative” are terms that Republicans hold in esteem and attaching yourself to that, whether it’s valid or not, is what you do. You try to create an image of being aligned to a certain group within the party, like being the Tea Party candidate or being the evangelical candidate. The image you project in a party primary is of being that committed partisan, so you can still appeal to different segments.