The media play a crucial role within Britain’s Establishment. By focusing their fire at those at the bottom – often with coverage based on distortions, myths and outright lies – they deflect scrutiny from the wealthy and powerful elite at the top of society. All of which is hardly a surprise, given that their owners are themselves part of that elite, ideologically committed to the status quo. Because of how and by whom they are run, much of the media today serves as a highly partisan defender of the interests of those with wealth and power.

It was the tightest election campaign in Britain for a generation. In April 1992, after thirteen years in the electoral wilderness – years of mass unemployment, union-bashing and the selling off of public assets – Labour and its leader Neil Kinnock were on the cusp of regaining power from the Conservative Party, led by Thatcher’s successor John Major. On 2 April – a week before voters were due to march to schools and village halls to cast their ballots – one poll projected that Labour was on course for a 6-point win. But the creeping jubilation of the party’s grassroots was matched only by the horror of Britain’s media elite at the prospect of a Labour victory. After playing a crucial role in cementing Thatcherism and demolishing its opponents, Fleet Street was not about to risk any of the grand achievements of the 1980s being stripped away. Labour – and its leader – were subject to one of the most vitriolic media campaigns in post-war British political history.

Nearly a quarter of a century after his media mauling, Kinnock takes me for coffee in the canteen of the House of Lords. He may have supported the abolition of the House of Lords all his life, but he now sits there as a peer. What remains of his famous ginger hair has turned grey, but his gravelly Welsh accent remains. Kinnock was once savaged as the ‘Welsh Windbag’, and it is easy to see why: he rarely uses a sentence when a paragraph will do. Although he can be verbose, he is eloquent and often passionate, but his answers are punctured with bitterness, not just against the right, but against members of his own party and movement.

As far as Kinnock is concerned, this campaign was not, above all else, a personal campaign directed against him, but rather against ‘an increasingly successful and appealing Labour Party’. Determined that Labour must not win, ‘the editors of the tabloids, except for the Daily Mirror, got together on the Thursday before the poll,’ explains Kinnock. ‘They decided they would coordinate their attacks on the Labour Party.’ Two days later, The Sun, Daily Express and Daily Mail regurgitated an earlier speech made by the Tory Home Secretary, Kenneth Baker, alleging Labour plans for an ‘open-door’ immigration policy. The Daily Express, Kinnock recalls, even gave away thousands of free copies in key marginal seats. ‘Part of that was against me,’ he says, ‘but basically it was simply anti-Labour. Against a Labour Party that they thought was in danger of winning.’ On election day itself came The Sun’s infamous front-page exhortation: ‘If Kinnock Wins Today Will the Last Person to Leave Britain Please Turn Out the Lights’. The Tories duly won the election from under Labour’s noses, leading the jubilant newspaper to boast the following day: ‘It’s The Sun Wot Won It’.

It was not all down to the media. Labour’s leaders hardly inspired the electorate, and a foolishly triumphalist rally in Sheffield on the eve of the election did not help: Kinnock had taken to the stage excitedly yelling ‘We’re alright!’ But this episode alone underlines what remains an essential truth about the British media. There is not a free press in Britain: there is a press free of direct government interference, which is a different thing altogether. Instead, most of the mainstream media is controlled by a very small number of politically motivated owners, whose grip on the media is one of the most devastatingly effective forms of political power and influence in modern Britain. The terms of acceptable political debate are ruthlessly policed, particularly by the tabloid media; those who fall foul of them can face crucifixion by newspaper. The media, in other words, is a pillar of the Establishment – however much many journalists may find this an unpalatable truth.

‘It clearly isn’t a free media,’ current Labour shadow cabinet minister Angela Eagle tells me as we sit in the café of Parliament’s Portcullis House, which swarms with ministers, backbenchers, journalists and ambitious researchers. ‘It’s a media that’s ideologically driven by its owners who have particular views that you or I probably wouldn’t agree on an awful lot of the time. I just wish that was pointed out and understood a bit more.’

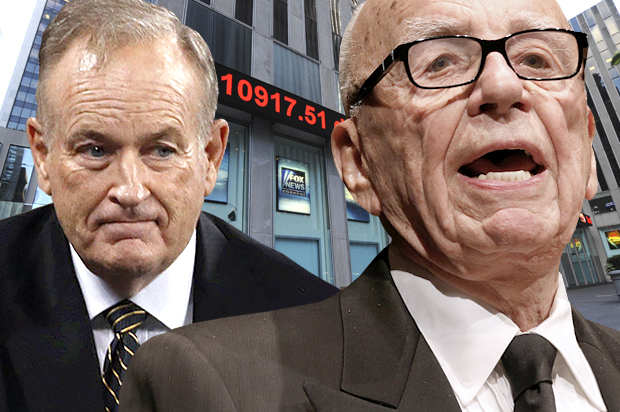

Back in 1992, the systematic monstering of Kinnock and Labour was not simply born out of a panic that the policies of the 1980s – which, after all, helped forge the modern Establishment – might be driven into reverse. In the 1970s the leading outrider Madsen Pirie had spoken of a ‘counter-ratchet’ to reverse the post-war consensus. Who could say for sure that a Labour victory in 1992 would not do the same to the post-1980s Establishment? Throughout his leadership Kinnock had suggested that the power of the media could be curtailed under a Labour government. In 1986 he had proposed importing US legislation restricting foreign ownership of the media, which would instantly have disqualified Rupert Murdoch, a US citizen, from owning British newspapers. ‘And whilst it might be that proprietors would want to change their nationality to British, in order to conform with the requirements of the law,’ a smirking Kinnock tells me, under a Labour government ‘these applications would gather thick dust in the pending tray of the Home Secretary.’ It was, he states, at this point that Murdoch ‘decided that things had to move from antagonism to war-level attack’.

Tom Watson is a burly, bespectacled man with a discernible West Midlands accent. For him, the struggles of the 1980s still loom large. When we met in his parliamentary office, he was Labour’s election fixer, but he resigned in July 2013 after writing a letter assailing ‘the marketing men, the spin people and the special advisors’. He has long been portrayed as a machine politician, a bruiser who was blindly loyal to his mentor, Gordon Brown, an image that he strongly resists. When he joined the Labour Party as a fifteen-year-old in 1983, he says, the party had ‘nearly murdered itself’. The battleground, as he then saw it, was against left-wing ‘entryists that took over the party’, and Labour ‘became super pragmatic’ so it could win elections to ‘deliver for the people we represent’. But his realization of the role of Britain’s media made him revise all that. ‘This was a misportrayal of what was going on,’ he says. ‘What was going on was a secret meeting between Margaret Thatcher in 1981 at Chequers where Rupert Murdoch had done a deal to buy The Times and The Sunday Times.’ Murdoch had briefed Thatcher about his plans, including taking on the trade unions and slashing the workforce by 25 per cent. After this meeting, the Thatcher government did not refer Murdoch’s takeover bid to the Monopolies and Mergers Commission, which could have blocked what became Britain’s largest newspaper group. ‘It was about courting a very powerful media who could make or break politicians.’

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s the Murdoch press had loyally defended the Thatcherite project, tackling and demonizing opponents ranging from Labour councils to trade unionists. It was a natural marriage. Murdoch was a strident proponent of small-state right-wing populism. But after he had helped catapult John Major into Number 10 in April 1992, the wheels soon came off the Tory bandwagon. When, just a few months after Kinnock’s pasting, Britain was catastrophically ejected from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism on so-called ‘Black Wednesday’ on 16 September 1992, billions of pounds were lost, Conservative economic credibility was shredded, and Major’s increasingly chaotic administration lurched from crisis over the European Union to scandals involving the personal lives of ministers. But crucially, change was apparently afoot within Labour’s ranks. After the old-style social-democratic leader John Smith abruptly died in May 1994, he was replaced by the charismatic right-winger Tony Blair, who pledged to scrap Labour’s historic commitment to public ownership, among other long-standing principles. New Labour, as it styled itself, no longer seemed to pose any threat to the political settlement established by Thatcherism. In July 1995, as the Tories became a national laughing stock, Blair flew to meet Rupert Murdoch in Australia’s Hayman Island and – two months before the 1997 election that swept New Labour to power – The Sun dramatically swung behind him.

‘The treatment that I’d received scarred Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, and made [New Labour spin-doctor] Alastair Campbell absolutely wild with rage,’ is how Kinnock rationalizes it. ‘So they were going to try, if they could, to neutralize insofar as they could that antagonistic press.’ As far as the New Labour elite were concerned, winning over The Sun was crucial to their chances of victory.

David Wooding is not your typical Sun journalist. He hails from a working-class background in Liverpool, a city that rejected his newspaper after it spread police lies about the circumstances in which ninety-six football fans of Liverpool FC died in the Hillsborough Disaster of April 1989: many Liverpool newsagents still boycott The Sun, and its current circulation in the city is barely a quarter of the 55,000 copies it sold daily before the disaster. Wooding is a prematurely white-haired man with a glass eye – the legacy of a car crash in his youth – whose demeanour is brisk but friendly. In the 1980s he had worked with Alastair Campbell, an abrasive Labour-supporting hack who was poached by Blair from the Daily Mirror. On the night of the 1997 election Wooding, a news reporter for The Sun, was covering Blair’s Sedgefield parliamentary constituency, when Campbell called him into his office. ‘I asked what was the biggest turning point in the election campaign,’ Wooding recalls, ‘and he said, without doubt, the biggest turning point which led to Labour being elected was when The Sun came out in support of us.’

‘I can understand Blair’s desire to tone down the hostility,’ says Tom Watson. ‘Remember the movement was at war with The Sun newspaper, or The Sun newspaper was at war with the movement, so I can understand him wanting to establish a personal relationship with this powerful, important media figure.’ Watson comes across as relaxed, leaning back in his chair with his hands behind his head, but he is a man who has more reasons to be bitter about the alliance between New Labour and Murdoch than most. In 2006 he had resigned from Tony Blair’s government and urged the Prime Minister to follow him. Blair was furious, describing Watson as ‘disloyal, discourteous and wrong’, but in the event Watson’s walkout helped to speed up Blair’s own resignation as Labour leader in June of the following year. Yet Watson was convinced that Blair’s News International friends had pledged to destroy Watson’s career as an act of revenge. In 2009 The Sun wrongly claimed that the former defence minister was part of a conspiracy to smear Tories by making up embarrassing stories about their private lives. The newspaper ended up having to pay him libel damages.

Watson’s own experience underlined how Blair’s relationship with the Murdoch empire went far beyond one of neutrality: it had become intimate. So much so, in fact, that Blair would end up becoming part of the Murdoch clan itself. After stepping down as Prime Minister, Blair was asked to be godfather to one of Murdoch’s young children and was present, robed in white, as the child was baptized at a ceremony on the banks of the River Jordan. ‘There’s something fundamentally wrong about any politician having that kind of secret friendship with someone in that position,’ says Watson.

The Murdoch empire had backed Blair’s New Labour because it believed that whatever threat the party once posed had been eradicated – partly because of its own efforts – and in any case the Tories were dead in the water. But Murdoch also believed he could win valuable political concessions from New Labour – which, in the event, he did. After New Labour came to power, News International hired the political consultancy Lawson Lucas Mendelsohn (LLM) to dilute the Employment Relations Act, a very modest piece of legislation on workers’ rights. ‘They successfully lobbied to create a piece of legislation that would prohibit people collectively organizing in [News International’s printing plant at] Wapping,’ says Tom Watson. ‘They’d driven the unions out and Murdoch wasn’t going to allow them to be driven back.’ Instead, the legislation allowed for staff associations, a company-controlled organization as a substitute for a trade union. But the political power exerted by the Murdoch empire was complex. Desperation to keep this powerful and dangerous beast onside meant that there did not even need to be direct pressure. New Labour politicians tried to avoid policies that might antagonize this media colossus. ‘There is a more subtle pressure they exerted where it’s the issues you wouldn’t take on or the way priorities were made,’ says Watson.

In the run-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, New Labour’s spin-machine was at its most frenetic, feeding the media spine-chilling stories of Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction. The most infamous example was its release of the so-called ‘dodgy dossier’, a report that was supposedly based on high-level intelligence work but which, it transpired, was largely plagiarized from a variety of sources, including an essay by a university student. Although newspapers such as the Daily Mirror and The Independent opposed the invasion, the media largely failed to scrutinize the government’s claims; even the liberal Observer newspaper backed the war. The Murdoch empire was particularly unstinting in its near-hysterical support for the planned invasion. All of Murdoch’s 175 newspapers across the world backed the war. The media became a pillar of the spin effort in the march towards conflict.

One prominent historian recalls speaking at a private function of the Sydney Writers’ Festival in 2003 and discussing ‘what I thought was the unravelling disaster in Iraq as a result of a war and the great paradox that you would win an overwhelming military victory and yet lose the peace so rapidly’. A highly senior Murdoch press figure instantly stood up and, in front of the assembled guests, laid into him. ‘It was sort of scary and ludicrous at the same time,’ he recalls, and it underlined to him just how zealously the entire Murdoch empire was devoted to the Iraq War. His own theory was that, having failed to break into China, Murdoch saw the Middle East as a new potential frontier for his newspapers and television channels, something that would only be possible if the region was remade by US power. ‘If the Murdoch papers had been against the Iraq War, I’m sure the Iraq War would not have happened,’ says Chris Bryant, a former Labour Foreign Office minister who voted for the invasion.

When in June 2007 Gordon Brown replaced Blair as Prime Minister, he was keen to announce an inquiry into the Iraq War, to show that he represented change from the previous administration. But he faced pressure from a number of directions – civil servants whispering in his ear that it would be wrong to do so while British troops were still on the ground in Iraq, and Blairite MPs who threatened to cry betrayal. And again, the media played a key role.

Damian McBride was one of Brown’s key henchmen. Starting out in the civil service, he became the Treasury’s Head of Communications in 2003, when Brown was still Chancellor. Two years later, he became one of Brown’s key advisors, but in 2009 leaked emails to former Labour spin-doctor Derek Draper suggested the two were involved in a plot to smear key Tory politicians, not least by spreading rumours about their personal and sexual lives.

I was expecting McBride to be a thuggish bruiser, the type of spin-doctor who might turn up in the political comedy The Thick of It, ready with a volley of implausible expletives for anyone who went off-message. But on meeting him in a south London pub, I found a gently spoken, shy, ruddy-faced man who spoke candidly about his former master. According to McBride, Prime Minister Brown would almost certainly have declared the inquiry ‘if he hadn’t been worried about how the media would react, both in a defending Blair way, or defending themselves over Iraq – but also the attack that would have been done on him for declaring an inquiry while troops were still on the ground’.

The decision not to hold an inquiry into the Iraq War had potentially seismic political consequences. In the autumn of 2007, Brown appeared to be on the verge of announcing a general election, before he abruptly and catastrophically changed his mind after being wrong-footed by the Tory frontbenches over inheritance tax. His government never recovered from the debacle. But failing to declare an inquiry into the war was also a factor. ‘Iraq became a bit of a stick for disaffected voters to say, “Nothing’s changed under him”,’ explains McBride. Some voters had abandoned Labour for the Liberal Democrats over Iraq and regarded the war as part of the overall reason for no longer trusting Labour. ‘It could have made the difference in the 2007 judgement.’

So important were the media barons under New Labour that Blair or Brown would visit them as though they were paying homage in a royal court. McBride recalls how, along with financiers, journalists were the ‘only people’ that the Chancellor or Prime Minister would visit; it was a ‘huge reflection’ of the media’s power that, at the drop of a hat, Gordon Brown would be ‘whisked off in a car to go to the Daily Mail to sit down and have a meeting with [editor] Paul Dacre’. Meanwhile, other heads of industries would have to schedule meetings with Brown, their discussions carefully minuted by civil servants. Such meetings would be formally structured, and after going through the detail, those attending would be informed: ‘Thanks very much for presenting your position and we’ll look at it carefully.’ Not so with the media barons. Brown would go to dinners alongside them where, as McBride puts it, ‘you knew a lot of stuff would get done’ – people meet-ing ‘one-on-one with no one listening in, no civil servant listening to the conversation’. These dinners and meetings were shielded from any form of accountability. Nobody knew what sort of deals were struck.

It is a set-up that gives media barons great political clout. ‘I never saw an instance where Gordon had gone in saying, “This is black”, gone and seen Rupert Murdoch and come back and said “This is white”,’ McBride clarifies. Yet the wishes and desires of these unelected media tycoons did help craft the policies of an elected government, McBride says – and on many occasions, too. ‘There were lots of instances where he would’ve been “I’m in two minds about this”, and then come back and said, “No, we’re absolutely not doing that”, or “We absolutely are doing this.” Some of those [policy areas] would be very specific to their industry, but some of it would be quite general. He would suddenly take a massive interest in a particular policy because someone had expressed a view to him and said this was a priority for them.’ The priorities of the media elite became the priorities of the government itself.

The political views of media owners set the tone for their newspapers, transforming them into effective political lobbying machines. The editors of media outlets will often claim they are simply reflecting the views of their readers. When for example in 2007, Peter Hill, editor of the Daily Express, was asked by a Parliamentary Committee what he thought the role of an editor was, he replied: ‘I think we should speak for our readers and for the people of Britain in the way that we see it.’ But according to McBride, proprietors and editors would privately concede to politicians that they didn’t ‘give a toss’ what their readers thought – ‘This is about my personal views.’ Nor is The Sun on Sunday’s David Wooding coy on the issue: ‘Does The Sun support somebody because that’s what the readers think, are we going with the flow of the readers, or are we trying to influence the readers? There’s no doubt The Sun does express its own view. It has a line and it sticks to it.’

Whereas just 36 per cent of voters opted for the Tories at the 2010 general election, 71 per cent of newspapers by circulation backed David Cameron’s party. Throughout 2013, polls consistently gave Labour a solid lead in the opinion polls, with the Conservatives generally languishing at between 28 per cent and 33 per cent. And yet most mainstream newspapers remained supportive of the Conservative-led government, which gave the lie to any idea that they were simply the mouthpieces of British public opinion. While polls consistently demonstrated that a large majority of the British public wanted, say, renationalization of the railways, energy and the utilities; rent controls; the introduction of a living wage; and increased taxes on the rich – no mainstream newspaper endorsed such calls. Quite the reverse. The media is almost entirely committed to Establishment policies and ideas, which they attempt to popularize for a mass audience.

The tax-avoiding Barclay Brothers – Britain’s richest media figures – gain their formidable power through the Daily Telegraph. When I visit the London Victoria headquarters of this traditionalist conservative newspaper, I half-expect to walk through a time portal into the 1950s. Its open-plan office is the height of modernity, though; rows of fashionably dressed bright young things type furiously at high-end computers, while others sip lattes as they crowd around huge flat screens displaying rolling news coverage. The arrival of someone like myself – known to have values somewhat different from those of the newspaper – generates rather a lot of interest, and the odd bemused expression. The then-deputy editor (until a brutal purge at the newspaper in mid-2014), Benedict Brogan – a man with rimless glasses and whose dark eyebrows contrast sharply with his white hair – takes me to a side-office. Before we start the interview, he is keen for reassurance that I am not somehow intending to stitch him up. ‘Newspapers are not public services,’ he opines. ‘They are private combines, they are commercial operations, which are there in the hope of perhaps making money and selling their wares. I think it would be utter madness if you were to stand up and say the guy who owns the train set has no say over the train set. It would be defying the truth about newspapers throughout the ages. What is the point of owning a newspaper if you can’t take an interest in what the newspaper is up to?’

Brogan’s comparison with train sets is revealing: these newspapers are the toys, the playthings of their owners. And ‘taking an interest’ is a mild euphemism for the process by which owners stamp their ideological imprint on the papers, transforming their own private political agenda into a public force to be reckoned with. ‘It would be surprising if a newspaper reflected a spectrum of views that didn’t in some way coincide with the views of their owners,’ says Brogan. The problem with Brogan’s concession is that anyone rich enough to own a newspaper has a vested interest in an order that protects wealth and power. If it is inevitable that the newspapers’ opinions reflect, to some degree, those of their owners, then that ensures Britain’s media operate as the mouthpieces of wealthy interests.

The veteran journalist Christopher Hird was a stockbroker before working for media outlets such as The Economist and The Sunday Times. ‘The general position of the paper shapes what is written in the paper,’ he explains. ‘They are run by people who do believe in the private ownership of wealth and of assets, and who also believe in the supremacy of unregulated markets as a way of expressing public choices.’ These are the values by which journalists are expected to abide. ‘With the exception of The Guardian,’ says Hird, ‘all of the papers in Britain are owned by people who basically believe that if you work for them, that is the framework in which things are going to be written about. It’s also the case that some of them hold very reactionary right-wing and social views, and that also shapes the framework in which you work.’

Rupert Murdoch is more than open about his power. When it comes to The Sun and the old News of the World, he saw himself as a ‘traditional proprietor’ who exercised ‘editorial control’ over both The Sun and the News of the World, according to evidence he gave in 2007 to a House of Lords communications committee. ‘Mr Murdoch did not disguise the fact he is hands-on both economically and editorially,’ read the committee’s minutes. ‘He exercises editorial control on major issues – like which party to back in a general election or policy on Europe.’ He claimed not to have such power over The Times or The Sunday Times, but he would ring the editors to ask ‘What are you doing?’ It hardly seems likely that, with Murdoch on the other end of the phone, his editors would be inclined to do anything other than agree with him. At the Leveson Inquiry into the British media in 2012, Murdoch openly stated: ‘If you want to judge my thinking, look at The Sun.’ At the same inquiry, former News of the World editor Rebekah Brooks explained that, while she might have preferred more celebrity news, ‘in the main, on the big issues, we had similar views’. She was hired, broadly, because Murdoch knew she would be effective at ensuring the News of the World projected his own views.

Excerpted from “The Establishment: And How They Got Away With It” by Owen Jones. Published by Melville House. Copyright 2014 by Owen Jones. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.