The imperatives of literary fashion aren’t nearly as oppressive as they used to be, so in order to understand what it was like to be Angela Carter, writing in the 1970s and ’80s, we’ll have to use our imaginations. That’s fitting; the imagination was her kingdom.

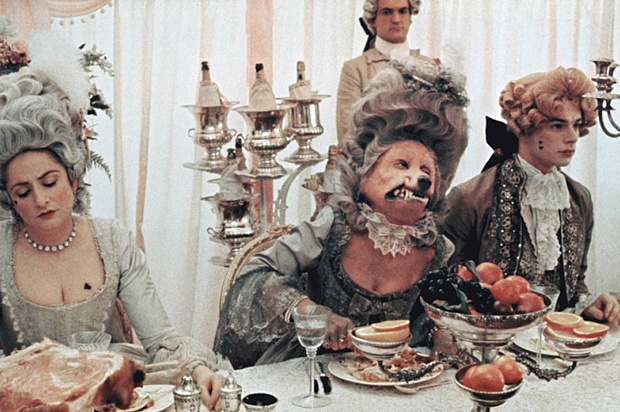

She wrote, however, during a period of ascendant realism, a literary moment that was all restraint and strangled epiphanies arrived at on wall-to-wall carpeting, with prose that read like Hemingway boiled down to the bones. Carter produced the opposite: fiction that was lavishly fabulist and infinitely playful, with a crown jeweler’s style, precise but fully colored. Granted, hers was also a time when mandarin postmodern novelists experimented with the sort of pop and folk culture she embraced, but those were largely cerebral escapades. Carter’s fiction has blood in it — and on it, as well.

Explaining Angela Carter to contemporary readers can be delicate. They are as likely to take offense at your presumption that they haven’t read her work as they are to have never heard of her at all. Her books are widely assigned in British colleges, revered by fans of speculative fiction stateside and have influenced writers as diverse as Rick Moody, Sarah Waters, Neil Gaiman, Jeff VanderMeer, Jeanette Winterson and Kelly Link. Salman Rushdie, who became her friend, described her as “the first great writer I ever met.” Yet her legacy has been a slow and stealthy one, invisible to many of the readers who have benefited from it. She left the door of realism unlocked when she strolled through it and lit out for the territories. Most contemporary literary fiction with a touch of magic, from Karen Russell’s to Helen Oyeyemi’s, owes something to Angela Carter’s trail-blazing.

On the 75th anniversary of Carter’s birth, Penguin Classics has reissued the collection many (including myself) consider her masterpiece, “The Bloody Chamber,” with an introduction by Link. Carter hated seeing these stories described as “retellings” of well-known fairy tales, because as far as she was concerned she was dismantling them. A child of south London (from which she was evacuated to Yorkshire during the Blitz) and of the ’60s, she was a socialist and atheist. After winning a literary prize in 1969, she took the cash, left her first husband and spent two years living in Tokyo, which is where she acquired her feminism. It was in Japan, she wrote, where she began her “questioning of the nature of my reality as a woman. How that social fiction of my ‘femininity’ was created.”

Although other Carter books are more conventionally “feminist” — notably “Nights at the Circus,” which, in 2012, was voted the best book in the venerable James Tait Black Memorial Prize’s 100-year roster of winners — it is “The Bloody Chamber” that has most enthralled readers. Carter would go on to become a significant figure in the revival of folklore and fairy tales as matter for scholarship and general reading, editing several collections in the early 1990s for Virago, the British press she co-founded with Carmen Calil. Yet she was not unambivalent about these stories, and her heady wranglings with fairy tales, with their complex relationship and appeal to women, ensured that she will not soon be forgotten.

Sex isn’t a subtext in “The Bloody Chamber,” but the text itself. (Carter would explain that she was only making explicit a “latent content” that is “violently sexual.”) The title story is a version of “Bluebeard” in which a fin de siècle ingenue, the churchmouse-poor daughter of a widowed music teacher, weds an older, thrice-married marquis who is “the richest man in France.” He sweeps her off to his ancestral manse, where she gets a suite in a tower and where her curious wanderings unearth his collection of kinky books. Then he departs on a suspiciously timed business trip, leaving her with a ring of keys and permission to visit every room, except one.

Eroticism hangs heavy in the air here, as it does in much of “The Bloody Chamber,” like an expensive, drugging perfume. There is something vampiric about the marquis’ perversity, and about his “white, heavy flesh,” which the narrator repeated compares to lilies. Yet she is aroused to see him watching her in a mirror “with the assessing eye of a connoisseur inspecting horseflesh.” She believes he can see into her soul, perceiving “a potentiality for corruption that took my breath away.” It’s not so much his power that entraps her, as her own longing for surrender.

Around the same time that “The Bloody Chamber” came out, Carter published a book length essay, “The Sadean Woman and the Ideology of Pornography,” that provoked the ire of a good number of her feminist comrades. A central argument of the book is that to choose a passive sexuality — one that revels only in being desired — is to choose victimhood. “Justine,” she wrote of one of the Marquis de Sade’s heroines, “marks the start of a kind of self-regarding female masochism, a woman with no place in the world, no status, the core of whose resistance has been eaten away by self-pity.” Carter also felt that de Sade was the first writer to imagine (some) women as sexual agents, liberated from the biological roles of whore, wife and mother, a liberation she devoutly wished for.

Imagination was not only her banner, but her sword. If you favor remaking the world, you must first imagine that some things considered inevitable, innate and eternal can be otherwise. But before you can even attempt that you must reckon with your own investment in the status quo. Carter has been described as the most un-British of British writers, and you can detect the French flavor of her feminism here. Like Simone de Beauvoir, she recognized that, while subjugation may be onerous, freedom can be terrifying.

The fairy tale, with its high formal consistency, its hypnotic repetitions and its deployment of archetypes, seems to fascinate female readers in particular. Does it, as scholars like Bruno Bettelheim have argued, describe the bedrock of human experience, that which can never — and therefore will never — change? Carter didn’t like that idea (it was the very “unnaturalness” of de Sade’s sexual libertinage that attracted her), but she still found it intriguing. If it was possible to break open the fairy tale and remake its tropes, then maybe it was also possible to remake womanhood itself.

Female captivity is a recurring theme in both “The Bloody Chamber” and in the old tales that inspired it. Carter’s stories are full of masterful older men, sexually experienced, rich and usually titled, very much like the heroes of romance novels. Some of them, like the Beast in “The Tiger’s Bride” and the eponymous hero of “The Courtship of Mr. Lyon,” are literal predators, a word that also comes up a lot in women’s erotica. Carter’s willingness to acknowledge the allure of such dangerous men — and women’s own perilous desire to be enveloped in, and perhaps even consumed by, their power — give “The Bloody Chamber” its potency. If you’d like to think this troubling fantasy has become obsolete, have a look at the pop-culture juggernaut that is “Fifty Shades of Grey,” itself an abjectly conventional retelling of “Beauty and the Beast.”

“The Bloody Chamber” dares to insist that not only can we keep what we love about fairy tales — their sensuality, their daring, their casting off of the constraints of the rational — but we can even harness them to our own ends. This is why the gorgeousness of Carter’s stories is indivisible from their feminism; she holds out the promise of new pleasures to replace the addictive old ones. Even when she is painting a horror, like the seduction of the narrator of “The Erl-King” by a forest elemental with plans to cage her, she uses every brush and tube in her box:

He strips me to my last nakedness, that underskin of mauve, pearlized satin, like a skinned rabbit; then dresses me again in an embrace so lucid and encompassing it might be made of water. And shakes over me dead leaves as if into the stream I have become.

Or in this description of a vampire, one of her rare female predators, but also a prisoner, in a mouldering castle, of her aristocratic heritage:

… A girl with the fragility of the skeleton of a moth, so thin, so frail that her dress seemed to him to hang suspended, as if untenanted in the dank air, a fabulous lending, a self-articulated garment in which she lived like a ghost in a machine.

Carter needed the fantastic, and the imagination it springs from, because she wanted to do justice to the beauty of the old ways and also to the wonders of the new ways she hoped would replace them. It’s no coincidence that both the literary fiction and the feminism of her time would drift toward the priggish and the prohibitive; so much attention to what one shouldn’t do! She was a liberationist in every sense of the word, a champion of unruly pleasures, always busting out of one tower or another and encouraging everyone else to do so, too. If our personal and literary spaces feel more wide open now, she’s one of the ones we have thank.