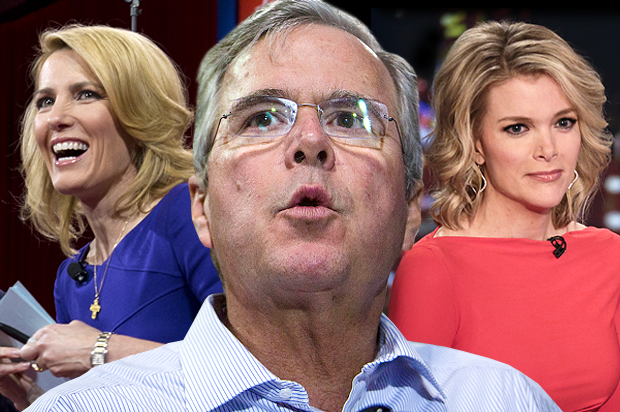

When Jeb Bush told Fox News’ Megyn Kelly that he’d still invade Iraq, even “knowing what we do now,” it did more than raise a few eyebrows. It turned Laura Ingraham, of all people, into a sage.

“I would’ve [invaded],” Jeb said in response to Kelly’s question, quickly adding, “And so would’ve Hillary Clinton, just to remind everybody, and so would’ve almost everybody that was confronted with the intelligence they got.”

But Ingraham, wisely, was having none of it. “What was the question? ‘Knowing what we know now.’ Not, ‘If you were in the same exact circumstances as your brother would you authorize this war?’ No, no, no! ‘Knowing what we know now.’ Namely that there were no WMDs. We got bad intelligence.”

As for Jeb’s contention that Hillary Clinton would do the same, Ingraham fairly snorted her contempt. “No Hillary wouldn’t!” Ingraham said. If you say what Bush said, “There has to be something wrong with you,” she explained. “We can’t stay in this relitigating the Bush years again,” she added. “We have to have someone who says, look, I’m a Republican, but I’m not an idiot. I’m not stupid. I am a conservative, and I learn from the past, and I improve myself. I don’t bring in the same people who make the same stupid decisions in the 2000s to get us into the 21st century.”

Ingraham fairly spit out the word “stupid” like it was a mouthful of poison, which she had every right to do. Yet, admitting past mistakes and learning from them is not just a problem for Jeb Bush, but for the entire GOP presidential field—even Rand Paul, now that he’s fallen into line on waging war on ISIS. The simplest explanation is that waging war has become deeply implicated in Republican and conservative identity. It’s not about admitting that you did something wrong, therefore; given this mind-set, it’s about admitting that you were something wrong. The culture wars are, as they have always been, wars of identity politics: to give up an inch is to give up everything you are. Rethinking who you are, reimagining, reinventing yourself—the most American of all acts, when you think about it—has now, ironically, become unthinkable.

Thus, Bush’s adamant refusal to learn from experience is emblematic of a broader attitude, which is hardly limited to fighting wars. (On Thursday, Bush again changed his answer and finally admitted that, knowing what we know now, he would not have invaded.) The ironclad opposition to raising taxes is another glaring example of this mind-set, wildly at odds with the actual tax-raising record of the right’s patron saint, Ronald Reagan. The reality of Reagan’s record versus the myth simply reinforces the underlying dynamic here: the conservative war on evidence, visible in everything from the birther movement to climate change denial, to the most recent committee vote slashing Amtrak funding, when Democrats were attacked for even mentioning the disastrous train wreck in North Philadelphia that had just occcurred.

But it’s not just limited to conservatives and Republicans. On the Democratic side, President Obama has seemingly learned nothing from decades of disastrously failed “free trade deals.” In 2003, after a decade of NAFTA, a report from the Economic Policy Institute by Robert E. Scott summarized the situation:

Since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed in 1993, the rise in the U.S. trade deficit with Canada and Mexico through 2002 has caused the displacement of production that supported 879,280 U.S. jobs. Most of those lost jobs were high-wage positions in manufacturing industries. The loss of these jobs is just the most visible tip of NAFTA’s impact on the U.S. economy. In fact, NAFTA has also contributed to rising income inequality, suppressed real wages for production workers, weakened workers’ collective bargaining powers and ability to organize unions, and reduced fringe benefits.

The trade agreement track record hasn’t improved since. To the contrary, earlier this year, Scott wrote a report, “Currency Manipulation and the 896,600 U.S. Jobs Lost Due to the U.S.-Japan Trade Deficit,” highlighting another aspect of how trade systematically savages the economy. Among other things, Scott noted:

- President Obama promised that the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement would increase U.S. goods exports by between $10 billion and $11 billion, supporting 70,000 American jobs from increased exports alone. However, in the first two years after that deal went into effect, U.S. exports actually declined, and growing trade deficits with South Korea cost nearly 60,000 U.S. Jobs.

- The United States has a large and growing trade deficit with Japan and the 10 other countries in the proposed TPP [Trans-Pacific Partnership]. This deficit has increased from $110.3 billion in 1997 to an estimated $261.7 billion in 2014.

- Several members of the proposed TPP deal are well known currency manipulators, including Malaysia, Singapore, and Japan.

- Eliminating currency manipulation by about 20 developing and developed countries (including Japan) could reduce the U.S. global trade deficit by between $200 billion and $500 billion each year, which could increase overall U.S. GDP by between $288 billion and $720 billion and create between 2.3 million and 5.8 million U.S. Jobs.

- Yet U.S. Trade Representative Michael Froman has testified that currency manipulation has not been discussed in the TPP negotiations.

Arguments against “free trade” agreements are hardly unfamiliar to President Obama. A major reason he is president has to do with his opposition to the Iraq War, of course. But his purported opposition to destructive “free trade” deals played a significant role as well, and this is where his record turns particularly troubling. In December 2007, still the underdog, he wrote to the Iowa Fair Trade Campaign:

Like you, I refuse to accept that we have to stand idly by while American workers lose their jobs, our communities struggle, and the American dream slips further out of reach. It’s time to start putting working people ahead of special interests and Washington lobbyists….

One of the first things I’ll do as President will be to call the Prime Minister of Canada and thePresident of Mexico and work with them to fix NAFTA. We’ll add binding obligations to protect theright to collective bargaining and other core labor standards recognized by the International Labor Organization. And I will add enforceable measures to NAFTA, the World Trade Organization (WTO),CAFTA [Central America Free Trade Agreement] and other Free Trade Agreements (FTA’s) currently in effect. Similarly, we should add binding environmental standards so that companies from onecountry cannot gain an economic advantage by destroying the environment. And we should amend NAFTA to make clear that fair laws and regulations written to protect citizens in any of the three countries cannot be overridden simply at the request of foreign investors.

So, back in December 2007, Obama had learned the painful lessons of history on trade—but since then, he’s forgotten them? In his own way, he’s as bad on trade as Jeb Bush is on Iraq. And his increasingly personal attacks on Elizabeth Warren have only made matters worse.

There’s a common factor on both these stories—the role of the media. On the subject of Iraq, media’s abject failure is what makes this whole GOP clown show even possible. As Think Progress noted in response to Bush’s performance, “The Iraq War, however, was not dictated by intelligence. Rather the administration cherry-picked, manipulated and ignored intelligence to support their predetermined outcome.” It went on to cite several supporting sources, including Paul Pillar, the national intelligence officer who oversaw the Middle East from 2000 to 2005, who wrote in 2006 that “intelligence was misused publicly to justify decisions already made,” and Mike McConnell, Bush’s director of national intelligence from 2007 to 2009, who “found the administration ‘set up a whole new interpretation because they didn’t like the answers’ the intelligence community was giving them.” All this is routinely ignored by the media as a matter of course.

But for the media, it’s not just a matter of hindsight, of learning the lessons the hard way—or failing to. You see, the media actually knew all this in advance—before the invasion, even before Congress voted in 2002. On Sept. 11, 2002, USA Today published a blockbuster story, “Iraq course set from tight White House circle,” which began by saying that the decision to invade Iraq came within weeks of 9/11, “without a formal decision-making meeting or the intelligence assessment that customarily precedes such a momentous decision.” It went on to note that, in essence, ignorance regarding Iraq was a feature, not a bug:

The White House still has not requested that the CIA and other intelligence agencies produce a National Intelligence Estimate on Iraq, a formal document that would compile all the intelligence data into a single analysis. An intelligence official says that’s because the White House doesn’t want to detail the uncertainties that persist about Iraq’s arsenal and Saddam’s intentions. A senior administration official says such an assessment simply wasn’t seen as helpful.

Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., a member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, calls that “stunning.”

“If we are about to make a decision that could risk American lives, we need full and accurate information on which to base that decision,” he says in a letter sent Tuesday to leaders of the committee and CIA Director George Tenet.

Following this revelation, an NIE was hurriedly produced, micro-managed by Cheney and the neocons. But anyone who took it seriously had to be willfully blind, given what had already happened. And what followed was more of the same. Bush and Cheney were certain that Saddam would not allow inspections, but when he did, UN inspectors found none of the overhyped evidence they were looking for. By the time the invasion took place—without the UN approval that had once been promised—it was not because everyone still believed the Bush/Cheney-generated lies, it was because those lies were on the verge of being conclusively disproven. Inspectors needed months to conclusively finish their work, chief inspector Hans Blix reported, but they were not allowed to do so. (Inspections finished after the invasion concluded there were no WMD.) The inspectors were forced to leave, so that the long pre-planned, but totally unjustified, invasion could begin. This was all openly known in real time. Then, after the war, the Downing Street memos added far more detail about how Bush/Cheney angled to con the whole world into war.

If Republican presidential candidates can’t learn anything from the Iraq fiasco, some of the reason must surely lie with the media that enables them. By burying the facts about how Bush and Cheney misled us into war—not as victims of bad intelligence, but as promoters of it, who changed their arguments as their original rationale faltered—the media protects not only the neocon GOP establishment, but the entire party from the hard work of facing up to its grievous mistakes—not least, the mistake of not asking hard questions in the first place.

But what about the Democrats on trade? Here, the media problem is far more systemic. For a wide variety of reasons, critics of “free trade” are simply not taken seriously by most in the media; they are treated condescendingly, at best. Name-calling is commonplace. Most in the media don’t even have a clue why they think like this—it’s simply “what’s done.” Whether or not the issues involved actually constitute “free trade” (as with currency manipulation, cited above, for example) is entirely beside the point; it’s enough to simply mouth the words. Further thought is not required, much less any consideration of evidence.

The fact that America is historically a protectionist nation—epitomized, though not limited to, Henry Clay’s American System conceived in contrast with the British system of free trade—is utterly foreign to them, beyond their comprehension. The historical reasons why this has changed, the arguments, unstated assumptions and historical forces involved—all this is terra incognita to them. In fact, as Thomas Ferguson argued in “Golden Rule: The Investment Theory of Party Competition and the Logic of Money-Driven Political Systems,” the New Deal Democratic coalition was based on donor blocks that were distinctly internationalist in their orientation, which at that time made them much less antagonistic to labor interests, which constituted a far smaller share of their costs. Much has changed since then, but all the political dynamics involved remain utterly opaque to a press corps rapt in its savvy fantasy of a transcendent understanding of how things work.

All of which makes them particularly incapable of grappling with what’s now happening in Democratic Party politics. One thing that’s striking is that Hillary Clinton has seemed far more willing to admit past mistakes than her GOP presidential rivals, or President Obama—sometimes openly, sometimes not so much. Her socially conservative stances around LBGT issues are now completely gone, despite the troubling background questions that remain; she’s evolved on driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants, and now promises to be more ambitious than Obama in supporting immigrant rights; her recent call for an end to the era of mass incarceration reflects a process that’s been underway for some time with her; and Huffington Post recently judged her “philosophically supportive of all 13 of the principles” in New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s “Progressive Agenda to Combat Income Inequality.” None of this means that Bernie Sanders should stop running for president, or that progressives more generally should relax. To the contrary—it’s an indication of just how much impact years of activism have had, and how much more such activism is needed in the future.

Clinton’s stance of openness to rethinking where she’s been in the past can certainly be cast as opportunistic pandering, just as Jeb Bush’s knee-jerk defense of the Iraq War may have been, given the sporadic war cries of his immediate rivals. Obama’s campaign statements criticizing “free trade” agreements were certainly no indication of what policies he would pursue once in office. So all such promises deserve to be viewed with some degree of skepticism. Yet, it’s also possible to spend too much energy arguing over how much a candidate is pandering, and pay too little attention to the substance and the political context involved. In particular, Clinton’s substantive moves to the left are concrete evidence of the difference made by years of grass-roots activist organizing—and all the more reason for such organizing to continue.

Bernie Sanders’ issue-driven challenge to Clinton ought to be seen in the same light. Sanders spent decades running for office in Vermont, building his base from the low single digits. He’s devoted his lifetime to altering the issue landscape, which has been the foundation for his eventual political success in Vermont. It’s not a new concept, but it is a neglected one on the national stage, which Sanders is breathing new life into. The argument over what issues should matter and why is the most basic argument there is in politics, from which all other arguments and answers flow. Sanders’ willingness to engage in it represents the extreme opposite of the unwillingness to reconsider past mistakes exemplified by Bush’s remarks on invading Iraq, and Obama’s remarks on trade.

There is a reason why voter suppression efforts have gained such prominence with Republicans in recent years: Their hold on power depends on it. But energizing voters to overcome such suppression is a far more complicated task. One has to engage with issues that touch their lives, and do so convincingly. One has to give them a reason to believe that things can be different, if we work energetically to change them.

In 2008, Barack Obama won the White House in large part by convincing folks he represented such change, but it was largely, as Naomi Klein pointed out in November 2009, a matter of branding in the same fashion that leading corporations had mastered in the 1990s:

A large part what I write about in “No Logo” is the absorption of these political movements into the world of marketing. And, you know, the first time I saw the “Yes, We Can” video that was produced by Will.i.am, my first thought was, you know, “Wow. A politician has finally produced an ad as good as Nike that plays on our, sort of, faded memories of a more idealistic era, but, yet, doesn’t quite say anything.” We think we hear the message we want to hear, but if you really parse it, the promises aren’t there, it’s really the emotions.

And, you know, I think that that explains in some sense the paralysis in progressive movements in the United States where we think, Obama stands for something because we-our emotions were activated on these issues, but we don’t really have much to hold him to because, in fact, if you look at what he said during the campaign, like any good super brand, like any good marketer, he made sure not to promise too much, so that he couldn’t be held to it.

Because it was branding, it proved particularly ephemeral, as the midterms of 2010 and 2014 showed. It’s taken a long time, years of struggle, disappointment and rededication on the ground, but we’re finally at the point where the fruits of those vague promises, tended by hardworking activists on the ground, are starting to manifest in a profusion of new forms. The work they’ve done has to be honored and respected. Unsettling work, challenging settled ways. Hard questions have to be asked—and answered—in the days ahead, if we’re to find our way forward, beyond endlessly repeating the failed policies of the past. Those who would lead us need to first prove they can follow the arguments the people have raised. Do they even know what the pertinent questions are? That’s where the real candidate questions should begin.