Television shows are hard to let go.

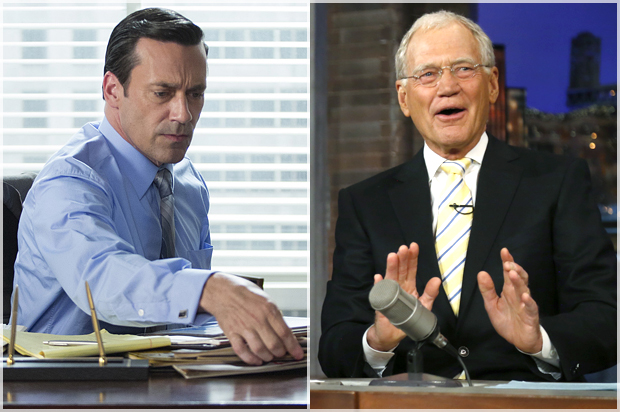

Partly that’s because the nature of the medium is one that stays with us for years. As I’ve observed before, watching TV is an investment of time—hours, if it’s all at once; a weekly commitment that can stretch over months, if it’s watched live; and years on end, if the show has more than one season. With a scripted show like “Mad Men” or “Breaking Bad,” both AMC shows with highly anticipated finales, that’s a five-year or eight-year commitment for viewers who were there from the pilot episode. With a talk show like “The Late Show With David Letterman,” that investment is not just years, it’s decades—22 years on CBS, following 11 on NBC. Television seeps into our collective veins and taints the collective groundwater; even if you don’t watch David Letterman, you might know he has these top 10 lists, and even if you don’t care about “Mad Men,” you have probably ascertained that it is about the ‘60s.

So when you do watch, and you do care, it becomes hard to say goodbye. You have to say goodbye to something you loved, and that means letting go of the part of you that lived with it for so long. The Sunday-night ritual of watching “Mad Men” with family on the couch. The Tuesday-morning work lull spent watching Conan O’Brien or Jon Stewart clips on YouTube. Friday mornings talking “Seinfeld.” Live-tweeting “Scandal” with your online friends on Thursday nights. With the two finales that are looming in the next week—“Mad Men” and “The Late Show”—there are a lot of us, fans and critics alike, who are wondering how we will replace the TV-show-shaped hole in our lives. It’s hard to move on.

So hard, in fact, that most TV finales of the last few decades have been hotly debated and/or outright reviled. “Breaking Bad,” “Seinfeld,” “Lost,” “How I Met Your Mother,” “Sex and the City,” “The Sopranos,” “Battlestar Galactica,” “Gossip Girl” and more, each with its own particular betrayals, heartbreaks and disappointments. (And this doesn’t even include the bizarre list of decades-old shows that ended by blowing everything up, or determining everything was a dream, or happening inside a snowglobe according to this one autistic kid.)

Even an adequate finale is disappointing, because it doesn’t seem like enough. Successful finales are the exception far more than the rule, but there are some: HBO’s “Six Feet Under” managed to nail the series finale for both its fans and critical audiences. Before that, “M*A*S*H” had a depressing but near-universally viewed finale to finish off a dearly beloved series. But those are lone outliers in a medium that asks its viewers to come along for a long journey. You’d think by now we’d all be better at handling the ends of TV series. But even if you watch all six seasons and the movie, too, it’s unlikely that you will be left with anything more than a few articles of tie-in merchandise and a lingering, vague sense of loss.

The rule seems to be that the more beloved a show is, the more disappointing its finale will be. For example: “Friends”’ finale was fine, because the show was largely just fine, especially by the end. That’s very different from “Breaking Bad,” which aired one of its best episodes, “Ozymandias,” just a few weeks before “Felina.” Loving a show seems to mean personalizing it—to making what happens in it happen to you, the viewer, even though you have not had any control over it from start to finish. When a show is beloved, fans have expectations. And not meeting those expectations makes us angry.

In fact, I feel pretty comfortable saying that the primary reason we all hotly anticipate finales and then vilify them immediately is because those are two of the five stages of grief: denial (one more episode before the penultimate episode of the final season of “Mad Men!”) and anger (“THAT. WAS. GARBAGE.”). What happens next is bargaining—which is expressed in the TV world mostly through rooting for spinoffs or some other kind of post-show second life. (“What about a show about Sally Draper?” “Maybe Letterman will drop in occasionally on Colbert’s show!”)

What follows, according to the Kübler-Ross model of grieving, is depression. Which is what all the bluster and rationalizing of the first three steps were trying to avoid—the actual sadness that a thing is gone, whether that is Joan Harris’ perfect pencil skirts or Paul Shaffer’s banter with Letterman in the Ed Sullivan Theater. Letterman, upon his departure, will have been a late-night host for a generation-and-a-half; “Mad Men,” when it goes, takes one of the most iconic and brilliant shows in the history of TV off the air.

The problem is, finales are depressing. They remind us a little too much of the latent, baked-in indignities of life: It never belonged to you. Time passes. Expectation doesn’t match reality. And there’s nothing you can do about that except watch it happen. Perhaps it hits us harder with television because so many of us use the medium as a way to entertain ourselves, to escape the unpleasant realities of day-to-day life. And yet not even TV shows can last forever.

But wait, you might be saying—isn’t there a fifth stage of grief, acceptance? There probably is. But you see, I’ve already changed the channel. Have you watched this show “Fresh Off the Boat”? It’s absolutely fantastic—lovely characters, wonderful family dynamics, very funny, very moving. It really means a lot to me already! Thank goodness, it got renewed for Season 2. I can’t wait to see what happens next. I’m going to be so sad when it ends.