September 11, 2001, started in New York as a particularly beautiful September day: there was not a single cloud, the air was transparent, and the light was crisp. I was less than three weeks away from the first anniversary of my joining the United Nations and had no sense of the momentous global changes that would be set in motion by the tragic events of the day. In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo three months later, Kofi Annan would say of September 11, with some flourish: “We have entered the third millennium through a gate of fire.” The historic importance of events is not always immediately perceived, but September 11 was almost immediately understood as the beginning of a new era.

I wrote in my notebook on the 12th of September: “This is as important as the Berlin Wall; it will change the relationship of the United States with the rest of the world.” To many of us, it was clear that the world had changed radically, but the direction it would take was unclear. The French ambassador to the United Nations, Jean-David Lévitte, was among those who immediately understood how critical it was to encourage the United States not to take a solitary path, but on the contrary to turn to the rest of world and to the United Nations for solidarity and support. As the French daily Le Monde put it in a banner headline on September 12: “We are All Americans.” Lévitte pushed hard for the quick adoption, just one day after the attack, of a wide-ranging resolution. The political intention was obvious, and I agreed with it: everybody expected the Bush administration to take action after such a devastating and humiliating blow, but it was important that the U.S. actions not challenge the post–World War II legal order.

However, the casual way in which the Security Council radically broadened the right of self-defense enshrined in the charter of the United Nations was worrying. Resolution 1368 recognized the right of member states to combat terrorism “by all means,” identifying as legitimate targets “those responsible for aiding supporting, or harboring the perpetrators, organizers and sponsors,” and inviting member states “to suppress terrorist acts, including by increased cooperation,” which meant that they could also act individually. We were moving away from the clarity of inter-state conflict, in which the right of self-defense had been restrictively defined so that use of force by a country without the explicit authorization of the Security Council would be the exception. What the Security Council was in effect doing was granting a member state—in this case the United States, but other countries could later avail themselves of the precedent—the right to launch strikes inside another country with which it was not at war, solely because it was deemed to “harbor terrorists,” and that was enough to assert the right of self-defense. Sergei Lavrov, who would later become the foreign minister of Russia, but in 2001 was still the Russian ambassador to the UN, wryly noted that the council had dropped the word “lawful” when affirming its determination to combat threats to international peace and security caused by terrorist acts. A sort of panic had in effect seized the world, but there was no conceptual framework ready for this new situation in which the central role of states as the guardians of law was being challenged. The balance between when a state can choose unilaterally to use force and when it must pursue a more collective process involving the Security Council had changed.

The ground for this evolution had been prepared during the Clinton administration, when in the summer of 1998 the United States launched cruise missiles against targets in Afghanistan and in Sudan, in response to the bombing of American embassies in Africa. But the operations that were launched in November 2001 against the Taliban regime were of a different order of magnitude. The Bush administration, probably encouraged by British diplomacy, formally informed the president of the Security Council of the actions taken, but no mention of the United Nations was to be found in the letter simultaneously sent to Congress. There was also an ominous mention in the U.S. letter to the Security Council of “other organizations and States” that possibly could be targeted. That did not go unnoticed in the Arab world. The circumstances under which use of force in self-defense could be considered had been dramatically expanded: the international community would be informed, but it was the sovereign decision of the United States to determine when, where, and how it would wage what was beginning to be called the “war on terror.”

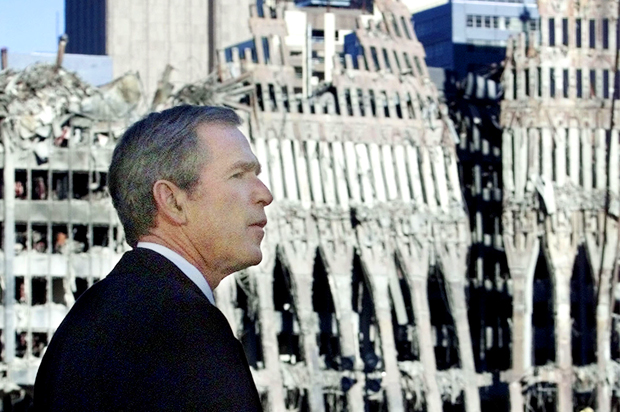

The way President Bush defined the fight against the terrorists of September 11 was to have a profound impact on the way the United States saw itself and was seen by the rest of the world. There was a fleeting moment, illustrated by the quick adoption of the UN resolution, during which the whole world seemed to come together in a genuine, even if superficial, show of sympathy. French president Jacques Chirac, who would later be described as public enemy number one of the United States during the run-up to the Iraq war, was genuinely moved when he arrived in New York a few days later as the first foreign head of state to visit the still-smoldering ruins of the World Trade Center. He met Kofi Annan for lunch immediately afterward. This would be the first of many occasions where I saw the French president and the secretary general together. Their relations were always cordial, even though France had been a staunch supporter of Annan’s predecessor Boutros Boutros-Ghali and probably had been initially suspicious of a candidate so strongly pushed by the United States. But France is generally supportive of the United Nations—where its permanent seat on the Security Council gives it more clout than it might otherwise have in world affairs—and it quickly understood that Kofi Annan would be a good partner. At a personal level, it was clear that the two men had a mutual liking, as they recognized in each other a real humanity, an interest in people. But they could not be more different: an understated African aristocrat and a populist French politician, a feline sprinter and a boxer with a heavy frame.

Chirac was happy that there was a broad consensus on the fight against terrorism and insisted that it should be a collective fight. “There was no alternative to the United Nations in the fight against terrorism,” he said. He had come to New York from Washington and described George Bush as a “man with an open mind,” and Colin Powell as a “wise man.” Vice President Dick Cheney had not spoken much, but “what he had said was reasonable,” and “Condoleezza Rice had not opened her mouth.” He confirmed what I had concluded from the resolution, that the United States would not go to the Security Council before taking action, but he added: “It does not really matter; it is a detail for technicians.” The bitter discussion about Iraq that started a year later was to show that those details did matter, and that one of the great achievements of the post–World War II period was under threat: at risk was a common, albeit limited, understanding of international law with respect to the use of force.

This legal issue that was being so lightly brushed aside pointed to a more fundamental question: Would September 11 bring the world together, or on the contrary, pull it further apart? The United States, in contrast to most other nations on earth, had never been exposed to an attack on its homeland during the last century, except for Pearl Harbor, but Hawaii was not yet a state of the Union at the time. For the first time since the War of 1812, the United States felt truly vulnerable to foreign attack, which is the common lot of most nations around the world. Americans had “lost their innocence” as Chris Patten, the European commissioner for external relations and a sharp mind, would tell me a couple of weeks later in Brussels. Would that sense of shared vulnerability bring greater proximity and solidarity—and the rest of the world seemed to be ready for that—or would it, on the contrary, push a wounded country into a more assertive nationalism driven by fear, and create more divisions in a world already fractured by enormous differences in wealth? Kofi Annan, a few weeks later in his Nobel speech in Oslo, would try to encourage the United States and the world to take the first path. He said:

If today, after the horror of the eleventh of September, we see better, and we see further—we will realize that humanity is indivisible. New threats make no distinction between races, nations or regions. A new insecurity has entered every mind, regardless of wealth or status. A deeper awareness of the bonds that bind us all—in pain as in prosperity—has gripped young and old.

Unfortunately, President Bush’s famous declaration that “either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists” became an excuse not to try to understand what kind of world could make such extreme violence possible. Trying to understand became conflated with trying to excuse. And those who did seek an understanding often seemed to suggest a kind of symmetry that could only be perceived as a cruel insult to the thousands of victims who had died on September 11. When I read “The Algebra of Infinite Justice,” an article written by an Indian writer I usually admired, Arundhati Roy, I was at times profoundly shocked, at times in agreement. I admired her when she wrote:

America’s grief at what happened has been immense and immensely public. It would be grotesque to expect it to calibrate or modulate its anguish. However, it will be a pity if, instead of using this as an opportunity to try to understand why September 11 happened, Americans use it as an opportunity to usurp the whole world’s sorrow to mourn and avenge only their own. Because then it falls to the rest of us to ask the hard questions and say the harsh things. And for our pains, for our bad timing, we will be disliked, ignored and perhaps eventually silenced.

I was shocked when she wrote, “The message [of the attacks] may have been written by Bin Laden (who knows?) and delivered by his couriers, but it could well have been signed by the ghosts of the victims of America’s old wars.” But I thought she was largely right to warn:

The U.S. government, and no doubt governments all over the world, will use the climate of war as an excuse to curtail civil liberties, deny free speech, lay off workers, harass ethnic and religious minorities, cut back on public spending and divert huge amounts of money to the defense industry. To what purpose?…Terrorism as a phenomenon may never go away. But if it is to be contained, the first step is for America to at least acknowledge that it shares the planet with other nations, with other human beings who, even if they are not on TV, have loves and griefs and stories and songs and sorrows and, for heaven’s sake, rights. Instead, when Donald Rumsfeld, the U.S. defense secretary, was asked what he would call a victory in America’s new war, he said that if he could convince the world that Americans must be allowed to continue with their way of life, he would consider it a victory.

I could not accept the violence of her tone, the disingenuous way in which she seemed to equate the decision to kill with the benign neglect of human suffering that wealth usually produces. She established an unfair symmetry between the nihilistic violence of September 11, which had killed thousands, and the nihilistic materialism of a Western civilization driven by money and success, which does not make the choice of evil, which does not wittingly kill but has little understanding for the misery of millions. But she rightly understood that at the heart of the fractures of our world was a tragic lack of imagination and empathy, a juxtaposition of self-righteous, closed communities reflecting the absence of a genuine human community. I felt that for the United Nations, it was a defining moment. I wrote a long note to Kofi Annan, in which I tried to find the right tone.

My starting point was that a “global community” remains elusive and that “people are now more scared by globalization and its threatening diversity. They feel dependent more than they feel empowered. They want to assert what makes their community different and unique and long for the comfort of a homogeneous community in which familiarity breeds security; they want a limited horizon, not a borderless world. Hence, the paradox of growing parochialism in the age of globalization.” I continued, “In the permanent tradeoff between the opportunities of openness and the safety of a closed community, the closed community has won. More ‘gated communities,’ metaphoric or real, are coming.” I then turned to the attacks of September 11:

The abyss of hatred revealed by the attack is not confined to a few “mad” terrorists. It is shared by tens of thousands, and condoned by tens of millions of people, who deeply resent what they perceive as Western hubris and moral bankruptcy, and who denounce the gap between the functional and economic integration of the world, and its moral vacuity….The liberal consensus now under attack was a convenient one: it posited that the world, if left to its own devices, is largely self-balancing. …This was indeed a morally and politically expedient analysis: it reconciled ethics and efficiency (self-interest produced the best society); it did not put too many demands on the rich and powerful (especially the U.S., whose power, in that non-political view of the world, was subsumed in the anonymous power of the “Market”); it shifted the burden of efforts on the developing world, which had to mend its ways….It reflected the latest triumph of the age of Enlightenment and of the United States, as its most concrete expression. Its rejection by radical Islamists, but also by the religious right in the U.S. as well as by un-reconstructed leftists is a rejection of a functional view of the world, and the affirmation that values rather than interests govern societies and bring human beings together. Ethics and ideas are back as the dominant force in Human history. This can bring progress as well as disaster: historically, ideas have been much greater killers than greed.

I never sent the note, and I was certainly right not to. When I read it eight years later, as the global economic crisis provided a bookend to the first decade of the twenty-first century, it took a different meaning. But I am glad I did not send it: this was the work of an abstract French intellectual who had not yet quite become a practical operator. As a piece of advice, the note was useless. The United Nations and its secretary general, in a world of nation states, can do little to shape national perceptions. Empathy between different nations cannot be prescribed; it has to come from within, from national leaders who do not take the easy route of self-righteous nationalism. Other leaders in the United States and Europe might have seized the moment to foster that empathy, to change the discourse on justice, and bring the world closer together. The politics of solidarity rather than the politics of fear could have prevailed. But Kofi Annan could not go much further than the exhortations of his Nobel lecture. His priority had to be the more immediate implications of September 11 on the conduct of international relations, and Afghanistan was to be the first test.

Almost immediately after the attacks, it became clear that al Qaeda was the organization responsible, and that Afghanistan was the safe haven of al Qaeda. Until then, the United States had been more concerned about so-called rogue states than failing states. September 11 signaled that failing states could actually be more dangerous than rogue states. Nonstate actors could almost take over a state, as had happened in Afghanistan, without being subject to the checks and balances provided by traditional power politics. The world was discovering that the old structures of states were being destroyed by globalization much faster than new ones could be built. It was soon obvious that the government of the United States would respond, to avenge its humiliation and to send a clear message to all governments on the planet that they were responsible for what happened on the land they were expected to control, and that no government, no matter how fragile, could distance itself from nonstate actors using its territory. The traditional order in which states are the ultimate guardians of a world order had to be reestablished. The Bush administration could have—and in my view should have—tried diplomacy and pressed the Taliban to abandon bin Laden. It chose force instead and decided that the Taliban state had to be toppled. This fateful decision was the logical outcome of the posture that the international community had taken when it decided to break all relations with the Taliban regime and refused to recognize its authority over Afghanistan, although the Taliban came to have effective control over most of the country. This political isolation, which had been challenged only by Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, probably contributed to the weakening of state structures and to its association with a criminal terrorist organization. We still wanted an international order based on the sovereign responsibility of states, but we were willing to pretend that a state with which we had a fundamental difference did not exist. It is remarkable that more than ten years after September 11, we have not really overcome that contradiction.

Two days before the attacks in the United States, Ahmad Shah Massoud, the most respected Afghan leader fighting the Taliban, had been assassinated in his stronghold by Taliban agents. At the time, the war for control of Afghanistan was continuing, and the Taliban were winning. While their ethnic base was in the Pashtun south, their program was not an ethnic one, and since capturing Kabul in 1996 they had gradually taken control of the whole country, including the mainly Tadjik and Uzbek northern regions. Only a small part of the country remained under the control of warlords and other forces.

Subsequent U.S. support of the Northern Alliance—a loose coalition of non-Pashtun ethnic groups from the northern part of the country—radically changed the course of the war. In a few weeks starting in early October 2001, the combination of a ground offensive by the Northern Alliance, CIA intelligence, and a powerful U.S. air campaign routed the Taliban. From the moment the air campaign started, on an autumn Sunday, the outcome of the Afghan war was not in doubt, although the speed at which “victory” was achieved was a surprise, as it would be in Iraq in early 2003. In both cases, the international community overestimated the difficulty of the military campaign and underestimated the challenges of political stabilization. What is remarkable, looking back on those fateful weeks at the end of 2001, is how early some of the fundamental issues that dominate today’s debate on Afghanistan were identified, while at the same time major mistakes, for which we now pay a heavy price, nevertheless were also made.

A week after September 11, Hubert Védrine, the socialist French foreign minister who was accompanying President Jacques Chirac, had lunch at the United Nations with Kofi Annan and myself. At this meeting he was already wondering whether Pakistan had the capacity and political will to act effectively in the fight against terrorism. I do not know if he had the opportunity to make his case to American officials, but in the intervening years, it has become abundantly clear that Pakistan, for which the issue of Kashmir remains a unifying national cause and a useful rationale for a big army, has great difficulties fighting the same terrorist cells that have launched operations in the Indian-occupied part of Kashmir. The fact that the Northern Alliance had Indian support increased the concern in Islamabad that Pakistan would lose what some of its generals have called “strategic depth,” that it would be squeezed between a hostile India and a hostile Afghanistan. After all, Pakistan intelligence services (the Inter-Services Intelligence or ISI) had handled as partners of the CIA some of the Pashtun factions that had fought the Soviets, like the Hezb-e-Islami of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, which later joined the Taliban. And many Pakistanis felt that an Afghanistan driven by a religious ideology—as the Taliban were—would be less of a threat to the territorial integrity of Pakistan than an Afghanistan driven by nationalism: Pakistan has fought Balush and Pashtun nationalism for decades and has had only limited control over its border with Afghanistan. Encouraging tribal leaders to have a religious rather than a national agenda remained a more attractive option for many Pakistanis.

In the fall of 2001, however, when the United States asked Pakistan to break ties with the Taliban and support the U.S. campaign, General Pervez Musharraf, Pakistan’s president, had no choice but to oblige. Nevertheless, as early as October 12, 2001, the first demonstrations against the American campaign took place in Pakistan. They were limited in scope and did not cause too much concern at the time. But they were a signal. I was amazed, a few years later, during one of my visits to Islamabad, to witness the depth of anti-American sentiment not just among lay people but among an elite that sends its children to the United States for their college education. It looked as if some members of the Pakistani upper class resented U.S. policies all the more because they knew they had no choice but to support them, and they would be doomed if the policies failed.

As the U.S. campaign started, the prestige of Kofi Annan was at its highest. After September 11, he had found the right words to express his compassion for the United States in a moment of national tragedy, and the U.S. government was making friendly gestures toward the UN. More than half a billion dollars in arrears owed by the United States were paid quickly. Kofi Annan suspected early on that after the U.S. campaign, a UN operation would be required. A journalist had mentioned that possibility in an article in the Guardian, and U.S. officials already were hinting at a possible UN role in Afghanistan. When I called Annan to congratulate him on his Nobel Prize, the conversation quickly turned to Afghanistan: Would it be like Somalia? Would the UN be caught in a fight between Afghan factions? What was the risk that the victory of one group over another would be wrapped in a UN flag, while Iran and Pakistan vied for influence and control? This was the first time on my watch that a new peacekeeping operation was being considered, and I was focused on the many different ways in which things could go badly wrong. I had not directly experienced Yugoslavia, Somalia, and Rwanda, but my initial reactions to the first major challenge of my tenure were shaped by the reports and analyses I had read on the tragedies of the 1990s, when UN peacekeeping was cast as a bystander to genocide in Europe and Africa. I would later acquire more direct experience, and possibly more confidence, but for better or worse I would never depart from that initial caution, for which I have sometimes been criticized.

Excerpted with permission from “The Fog of Peace: A Memoir of International Peacekeeping in the 21st Century” by Jean-Marie Guéhenno (Brookings Press, 2015).