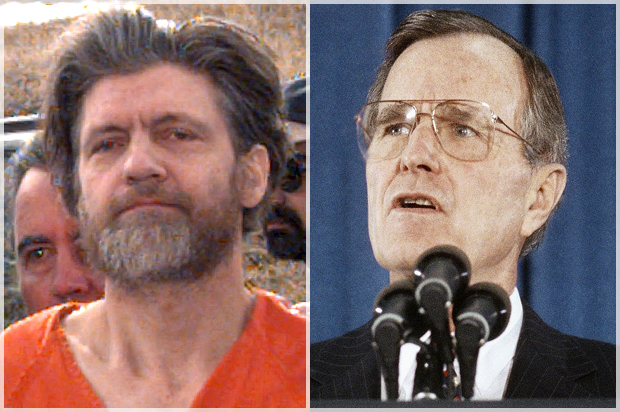

When President George H. W. Bush launched Operation Desert Storm with the backing of the UN Security Council to oust Saddam Hussein from Kuwait in 1991, another (albeit small) antiwar movement was born. Even before the war began, some students and Vietnam veterans organized marches in Boston, Boulder, Missoula, Minneapolis, Ann Arbor, and San Francisco protesting the stationing of American troops in the Persian Gulf. They carried signs that read, “No Blood for Oil” and “No More Vietnams.” Behind the scenes, in the military, antiwar sentiment was expressed by a surprising number of troops. When Marine Corporal Jeff Paterson’s unit was ordered to deploy to Saudi Arabia, Paterson sat down on the tarmac and refused to board the plane. He could have remained quiet and gone with the flow, he said, but he believed it was his duty to resist. “I will not,” he said, “be a pawn in America’s power plays for profit and oil in the Middle East.” Paterson was not the only service member to protest the war. West Point graduate David Wiggins, Marine Glen Motil, Army physician Harlow Ballard, and Army Reserve Medical Corps Captain Yolanda Huet-Vaughn all spoke out against the war, while more than a thousand Army reservists applied for conscientious objector status.

This Gulf War, however, was too brief for a full-fledged antiwar movement to emerge. If it had gone on longer, there is little doubt that more Americans, still unnerved by the bitter experience of the Vietnam War, would have protested the war. Because of its brevity the war was more of a television spectacle for Americans as they watched the daily images of the bombing of Iraq and the chaotic finishing off of Iraqi land forces on the evening news. Twelve years later, as we shall see, when the United States invaded Iraq a second time and stayed for nearly a decade, antiwar and antioccupation sentiment became a significant force that helped determine the outcome of the 2008 presidential election.

For most of the 1990s domestic issues dominated dissenting discussions. Ecological concerns, because the effects of environmental degradation are seen only gradually, usually do not get people as worked up as a war, with its more immediate impact. Nevertheless, environmentalists became increasingly more militant during the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century. Julia Butterfly Hill, for example, garnered a lot of media attention when she climbed into a thousand-year-old giant redwood that the Pacific Lumber Company was about to cut down and vowed not to return to earth until the company agreed to spare the tree. She wound up living in the branches of the redwood,

180 feet from the ground, for 738 days. Television and radio crews gathered around. Reporters were lifted up into the tree on cherry pickers to interview her. Supporters brought food and supplies, which she hauled up in a bucket. Finally, after more than two years of negative publicity, the Pacific Lumber Company acquiesced in Hill’s demands and pledged not to cut down the tree.

For years the literary genius and incorrigible gadfly Edward Abbey wrote essays, journals, and novels calling for the preservation of the wilderness and denouncing politicians and developers that were destroying these pristine areas. People must experience national parks on foot, not sitting on their fat butts inside air-conditioned Winnebagos and SUVs. If people must visit the national parks, Abbey insisted, let them walk.

Let the people walk. Or ride horses, bicycles, mules, wild pigs — anything—but keep the automobiles and the motorcycles and all their motorized relatives out. We have agreed not to drive our automobiles into cathedrals, concert halls, art museums, legislative assemblies, private bedrooms and the other sanctums of our culture; we should treat our national parks with the same deference, for they, too, are holy places.

. . . The forests and mountains and desert canyons are holier than our churches. Therefore let us behave accordingly.

Abbey’s most popular book was the best-selling novel “The Monkey Wrench Gang,” which developed a sizeable cult following among environmental radicals. It is the humorous account of an anarchistic gang of ecoterrorists who travel around the American Southwest blowing up billboards, dams, bridges, and other symbols of civilization that are destroying all that is good about America.

One of Abbey’s readers was Theodore Kaczynski, aka the Unabomber, who evidently took the tongue-in-cheek message of ecoterrorism a bit more seriously than Abbey might have liked. A sort of twentieth-century Luddite, Kaczynski was opposed to technological progress. “I read Edward Abbey,” he said in an interview after he was sentenced to prison; “that was one of the things that gave me the idea that, ‘yeah, there are other people out there that have the same attitudes that I do.’ I read ‘The Monkey Wrench Gang,’ I think it was. But what first motivated me wasn’t anything I read. I just got mad seeing the machines ripping up the woods and so forth.” Kaczynski lived in a remote cabin in Montana and for eighteen years mailed to academics and scientists at research and development laboratories letter bombs that killed three people and maimed more than twenty others. He was finally caught after the New York Times published his “Manifesto,” and his brother, recognizing his writing style and philosophy, tipped off the FBI.

Kaczynski’s goal was to start a revolution against technology, which he believed was destroying human life. “The Industrial Revolution and its consequences,” he proclaimed in the Manifesto, “have been a disaster for the human race.” They have “destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering (in the Third World to physical suffering as well) and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world. The continued development of technology will worsen the situation.” Therefore, he argued, there must be “a revolution against the industrial system . . . to overthrow . . . the economic and technological basis of the present society.” Though Kaczynski’s vision was misguided and unrealistic, it did draw attention to important problems that would otherwise be ignored.

The Unabomber was a solo act, but there were organizations that resorted to violence (although against property, not persons) to protest the degradation of the environment. The Earth Liberation Front (ELF) and Earth First! were two of the more notorious groups that grabbed headlines. Both organizations, like Greenpeace, used civil disobedience, but they went beyond protests and disruptive direct action campaigns such as tree sitting and road blockages. They also engaged in sabotage (which they call “ecotage”). Destroying ski lodges, pouring sugar into the gas tanks of Hummers parked in automobile-dealership lots, pouring chemicals on golf-course greens.

The Earth Liberation Front, the more radical of the two organizations, has been designated a domestic terrorist organization by the FBI. ELF does not shrink from the term ecoterrorism, but it does not seek to harm individuals. It has taken credit for torching a ski lodge in Vail, Colorado (because the lodge was expanding into a forest that endangered the habitat of the Canada lynx), and attempting to burn down the U.S. Forestry Service facility in Irvine, Pennsylvania. One of the spokespersons for ELF, Craig Rosebraugh, was subpoenaed in 2002, when the United States was embarking on the “War on Terror,” to testify at a congressional hearing investigating both foreign and domestic terrorism.

The history of the United States, Rosebraugh said in his statement, shows that social change only comes about through civil disobedience. Working conditions were only improved when workers went on strike or participated in protests and riots, women only got the vote when they picketed the White House, civil rights only became successful after the civil disobedience campaigns against segregation and the denial of voting rights, the Vietnam War only ended after massive demonstrations in the streets. “Perhaps the most obvious . . . historical example,” he said, “of this notion supporting the importance of illegal activity as a tool for positive, lasting change, came just prior to our war for independence. Our educational systems in the United States glorify the Boston Tea Party while simultaneously failing to recognize and admit that the dumping of tea was perhaps one of the most famous early examples of politically motivated property destruction.” We do not label our founding fathers as terrorists, but this is what the similar actions of the Earth Liberation Front are labeled by the federal government: ecoterrorism. “Yet, in the history of the Earth Liberation Front, . . . no one has ever been injured by the group’s many actions. . . . Simply put and most fundamentally, the goal of the Earth Liberation Front is to save life. The group takes actions directly against the property of those who are engaged in massive planetary destruction in order for all of us to survive. This noble pursuit does not constitute terrorism, but rather seeks to abolish it.” ELF has to take action because the government is not passing the laws and regulations needed to prevent the destruction of the forests. Those who take action “to stop the destruction of the natural world . . . are the heroes, risking their freedom and lives so that we as a species as well as all life forms can continue to exist on the planet. In a country so fixated on monetary wealth and power, these brave environmental advocates are engaging in some of the most selfless activities possible.”

Along with the radicalization of environmentalism a burgeoning antigovernment movement got a lot of press coverage in the 1990s, especially in the aftermath of events in Ruby Ridge, Waco, and Oklahoma City. Believing that individual liberty and the Constitution must be protected from an intrusive federal government, right-wing paramilitary militias in Michigan and Montana attracted many discontented supporters. They were antitax, antigovernment, and pro – Second Amendment. They armed themselves in order to prepare for the day when governmental restrictions on liberty would become intolerable. Just as the minutemen at Lexington and Concord stood up to unjust taxes and a despotic Parliament, so too must Americans stand up to the tyranny in Washington. The government must not interfere in their lives. They yearned for the supposedly good old days of the nineteenth- century pioneers who built this country through their rugged individualism. However, these modern-day minutemen overlooked the fact that it was the federal government that subsidized the railroads and irrigation projects that made it possible for settlers and homesteaders to move into the West and farm the land. Still, oftentimes what people believe about the past is more influential than what actually happened. When the FBI had shoot-outs with the Freemen of Montana at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, in 1992, killing two people, and with the Branch Davidians (a religious cult) at their compound in Waco, Texas, in 1993, which resulted in the deaths of seventy-six men, women, and children, membership in right-wing militias soared. These heavy-handed attacks were proof to many people of a vast government conspiracy to stamp out personal liberty and to establish a dictatorship. In 1995 the Michigan Militia posted a “Statement of Purpose and Mission” on its website:

“It shall be the sworn duty of this Militia to protect, defend, support, uphold and obey the Constitutions of the State of Michigan and the United States of America. Notice is hereby given that violations of either the State or National Constitution, by any alliance, nation, power, state, organization, agency, office, or individual shall be met with a fierce and determined resistance.”

On the second anniversary of the Waco shoot-out Timothy McVeigh (who was associated with, but not a member of, the Michigan Militia) staged a horrifying protest against the U.S. government by blowing up the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City: 168 people, including children in a day-care center, were killed, hundreds wounded. This act of violent dissent sickened Americans. For days the nation was in shock. McVeigh and his accomplices were quickly apprehended, tried, and convicted. (McVeigh was executed in June 2001; his accomplices received prison sentences.) Though McVeigh was not actually a member of any of the right-wing militias, the bombing and the trials discredited much of the antigovernment militia ideology. Still, these militias continue to gain members as they prepare to defend themselves against all enemies, foreign or domestic.

Excerpted from “Dissent: The History of an American Idea” by Ralph Young. Copyright © 2014 by Ralph Young. Reprinted by arrangement with NYU Press. All rights reserved.