The William F. Buckley house on Park Avenue was the dream of Manhattan’s cat burglars. We cannot know how Midas would have felt about the home, but we can be sure it was the envy of an Astor: For years Brooke Astor, an occasional guest, lived next door in extravagant decline. (Her son, wrote Buckley, had left her in a den of “untended wastebaskets, sofas reeking with urine and her pet dogs locked in a pantry.”)

William’s wife, Patricia, turned the maisonette into a quarry of precious metals and shiny trinkets that, for a certain kind of person, might necessitate sunglasses or anticonvulsants. Eclectic, hectic, and loaded in every sense, the duplex was a motherlode of hand-painted floor screens and mother-of-pearl tables, its walls splashed with flashy modernist paintings and lit with leaded Tiffany lamps. But despite the bonanza of gilded pier glasses and silver sconces and bronze flowerpots, it was a harpsichord that held the home together. The man-of-the-house’s chief contribution to the glittering litter was a seventeenth-century keyboard, and he placed it in the marble foyer so that guests saw it first—as if to clear any suspicion that his wife’s knack for chintz reflected on his personal taste in art. Buckley, who called the harpsichord “the instrument I love beyond all others,” had matching models in his Connecticut mansion and Swiss chalet; the conservative scion would entertain his visitors with a tune as often as an epigram. Bach was his muse as much as Edmund Burke.

This love of his provides a rare moment of peace in “Best of Enemies,” a turbulent, whiplash-inducing new film on the rivalry between Buckley and Gore Vidal. (In fact the music of Bach is a through-line in the documentary, serving as Buckley’s leitmotif.) After well over an hour of watching the men trade petty points and cheap insults—in archival footage, not the grave, though a psychic medium may easily prove otherwise—we see Buckley pull up his bench and play a Bach prelude in C, the simplest, most uncluttered of key signatures. The effort, contemplative and composed, is the film’s only moment of civility. (Early on, Vidal gives us an idyllic tour of his estate in Salerno, but he leads us immediately to the bathroom, where Buckley’s portrait hangs next to the toilet.) An amateur musician but not a dabbler, Buckley performed in the ’80s and ’90s with a roster of symphonies around the country, honing his skill with almost spiritual devotion. (“Art of any sort,” he once wrote, “is very, very serious business: that which is sublime can’t be anything less.”) His worship of Bach, a lifelong attachment, mirrored his intellectual manner. Like Bach’s themes, his arguments in writing and speech were famously complex, surprising, winding, and sonorous. As with any player of polyphony, Buckley showed considerable sleight of hand in teasing out parallels and resolving contradictions. Baroque music, which is contrapuntal, makes no great fuss about harmony, surely an appealing trait to a contrarian at odds with society. Like Bach, Buckley inevitably clung to the counterpoint.

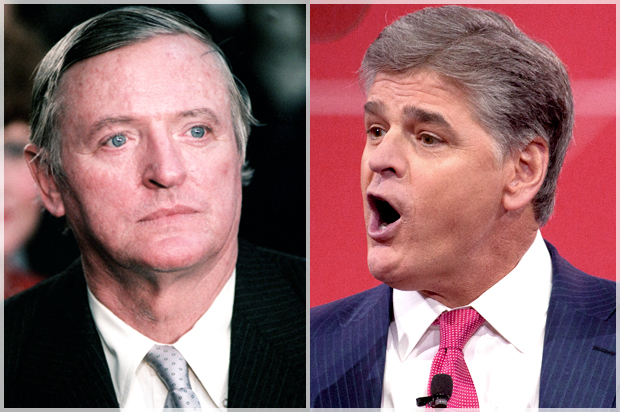

I harp on music because “Best of Enemies” harps on dissonance. Directed by Morgan Neville and the Oscar-winning Robert Gordon, this is a serious film by serious filmmakers, and it seeks to understand the decay of American commentary into white noise. Why, the film wonders, do Americans hope to divine the truth in 60-second shouting matches rather than 6,000-word features? Why do the opinion programs scuttle the well-read in favor of those who can barely decipher a teleprompter? Why does Fox News boom with the authority of Mount Sinai? Why, when parsing a point, do its hosts sound like a hernia is rending their groin? Why do our congressmen echo the same guttural sound bites? Why has the United States traded an intelligentsia for a punditocracy?

For Gordon and Neville, these rhetorical questions do not have a rhetorical answer, and they point their plugged ears at the rhetoric of Buckley and Vidal, whom they take to be the media’s original screaming heads. They circle the writers with yellow tape, saying they’ve found the epicenter of the shift. They diagnose Buckley and Vidal as patients zero of our madness, of our newsmen’s hysterics and our leaders’ strain of Tourette’s. At best, this is half true.

The decline and fall of the chattering class began in 1968, the filmmakers say, and in a certain sense they are right. In that year, ABC, one of three television channels, lagged far behind NBC and CBS in ratings, and when its competitors bought up the rights to report from the Republican and Democratic national conventions, the network hatched a plan. It would hire two writers to comment on the presidential nominees. They would perch on America’s left and right shoulders and vie for its conscience. But both of them acted like devils and raised hell from the first debate to the tenth. Despite the authors’ aristocratic airs and Mid-Atlantic inflections, Buckley hissed through his drawl as Vidal thumbed his Aquiline nose at him.

The clamor began well before the opening bell. As the film recalls, Vidal courted Buckley’s rage years earlier, lampooning him on “The Tonight Show.” At the Republican convention in 1964, Vidal embarrassed him again in front of a national audience, airing remarks from a campaign official about Buckley’s relationship with Barry Goldwater, then running for president. Before the 1968 debates, featured in the film, Vidal hired a researcher to help him smear Buckley and wrote his put-downs in advance, testing them on ABC’s cameramen and gophers. The liberal Vidal called his opponent a prophet of greed, the “Marie Antoinette of the right wing,” and the inspiration for Myra Breckinridge (the transsexual rapist in Vidal’s novel by the same name). When Vidal dismissed California’s conservative governor as an “aging juvenile actor,” Buckley defended Ronald Reagan by playfully dismissing Vidal’s film efforts. (“If ABC has the authority to invite the author of ‘Myra Breckinridge’ to comment on Republican politics, I think that the people of California have the right, when they speak overwhelmingly, to project somebody into national politics even if he did commit the sin of having acted in movies that were not written by Mr. Vidal”). Bickering became screaming in the melodrama’s final act, when Vidal labeled Buckley a “crypto-Nazi,” a weightier offense in postwar America than today, and Buckley called him a “queer” and threatened to “sock him in the goddamn face.” Buckley, a veteran of the Second World War, took the insult especially hard, having spent much of his career trying to purge conservatism of its anti-Semitic elements and having succeeded in marginalizing the John Birch Society.

If we believe the film, then, the ten-episode kerfuffle, shocking to ’60s viewers, was a historic moment on TV that changed discourse forever. We are reminded that at one point ABC’s studio at the convention actually collapsed — a metaphor for the shockwaves of the debaters’ sonic boom. While journalists panned the program as so much hot air, ABC sucked in a massive new audience and a windfall of advertising dollars. The hubbub was a boon, and the network and its competitors would try to revive the debates’ flare in future political coverage. They would prioritize noise over reason, shouting over thinking, and anoint pundits as America’s kingmakers.

But including Buckley in this category is more than a violation of good manners. As he might say about socialism — however wrongly, I might add — such a sentiment commits the sin of overreaching. Buckley, for all of his objectionable politics, was nonetheless the quintessential anti-pundit, and his example could serve as a timely antidote to the poor state of contemporary opinion, particularly in his own party.

Though Vidal said after the debates that he was glad to have given the audience “their money’s worth,” Buckley considered the argument a “disaster.” Vidal replayed the debates obsessively in his dotage, but they embarrassed Buckley to the end of his days, and he wished ABC had destroyed the tapes. (Buckley had wanted “to talk about the Republican Convention,” he said, but he found it “difficult to do so when you have somebody like this, who speaks in such burps and who likes to be naughty, which has proven to be a professional, highly merchandisable vice.”)

His outburst brought him lasting guilt, and Gordon and Neville show their sense of irony when Buckley plays Bach’s “Well-Tempered Clavier” midway through the film. If they give Vidal a theme, it is Purcell’s “Funeral March for Queen Mary,” a piece popularly associated with “A Clockwork Orange” — an allusion to the social, political, and rhetorical upheavals that Vidal helped kick off. (Vidal claimed in the Paris Review that he was “not musical,” which might explain the shrill tone of his essays.)

Noise is to music as confusion is to reason, and Buckley was as practiced a logician as a pianist. Indeed, the historian Sam Tanenhaus, interviewed at length in the film, describes him as the “great debater of his time.” Genuine debate needn’t traffic in shame or tinnitus, and Buckley eschewed the low-rung slur as much as he shied from the high-pitched shout. This is not to say that he wanted for wit, which he had aplenty, but that he used it only to ornament a fully developed theme. (If insults do not replace an argument, they can do healthy, illuminating work in revealing the hypocrisy or absurdity of a figure heaped in public praise. To object is to deny that character as well as ideology shapes history; it’s to deny that politics are personal.) Buckley would argue steadily and quietly, holding forth with a hushed assurance that would seldom rush or halt his opponent’s assertions. Like any trained musician, he had that quality of self-mastery which the world used to call virtue.

His willingness and eagerness to listen, the mark of an able and disciplined ear, and his love for the long phrase and extended argument gave him doubts about TV. Though Vidal said he would “never miss a chance to have sex or appear on television,” Buckley believed there was “an implicit conflict of interest between that which is highly viewable and that which is illuminating.” Yet the show he hosted, “Firing Line,” had an enduring impact on the marketplace of ideas: It ran for 33 years, longer than any other public-affairs program, and won an Emmy for its commitment to spirited inquiry. He questioned guests who agreed with him (Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek) as eagerly as those who did not (Jimmy Carter, Noam Chomsky, Saul Alinsky, Christopher Hitchens). Speaking to the show’s long format, a largesse for probing conversation, the economist John Kenneth Galbraith said that “’Firing Line’ is one of the rare occasions when you have a chance to correct the errors of the man who’s interrogating you.” Hitchens echoed the sentiment: “I did my first ‘Firing Line’ in 1983 and swiftly learned that if I left the studio cursing at what I hadn’t said, it was my own fault.”

Buckley’s desire to persuade rather than overpower, and his willingness to cope with the otherness of others’ views, earned him fast friends among the left-leaning intelligentsia. Galbraith, Murray Kempton, and Mario Cuomo all found in him a receptive and challenging companion. In the pages of National Review, the magazine he founded, he helped launch the career of Joan Didion, though her liberal awakening happened later. His lifelong friendship with Norman Mailer is the subject of a new book by Kevin Schultz, “Buckley and Mailer,” that gives the lie to the film’s charge of divisiveness. It is a meticulous portrait of two radicals who meet at the margins.

Buckley even has my own respect, though I find many of his positions odious. I’m at least as leftist as the late Mr. Vidal, but I stick my fingers in my ears only half as much. Buckley’s brand of anti-statism, his hatred of the New Deal and the Great Society and federal intervention of any kind, owed to a neurotic Cold War fear of collectivism. (His anti-interventionism even led him to oppose the Civil Rights Act, a heinous lapse of judgment that he later recanted.) In Vietnam he thought we were staring down the Four Horsemen. All his life, he kissed the ring of the war criminal Henry Kissinger. His fear of big government excused the worst indignities of big money, enshrining inequality as patriotism. “The socialized state is to justice, order, and freedom what the Marquis de Sade is to love,” he once wrote, rather sadistically.

As with many conservatives, his defense of liberty against the state was genuine but misguided. He despised totalitarianism as fiercely as I do, and he railed against the Soviet Union in an era of détente. But on a domestic level, I part from him on the matter of social welfare, in that I consider freedom null and void if swaths of the population are so disenfranchised they can’t make full use of it—economically, politically, biologically. Unlike my opponents, I refuse to forget the third item in Jefferson’s list of inalienable rights: “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Some found Buckley calculating and cold. His rhetoric, they said, was all head and no heart. It is a charge often brought against Bach, this idea of enthroning reason and suppressing the passions. It is also a common criticism of Plato.

Yet conservatism fills an important role in society. In the body politic, the right hand is as essential as the left. Liberals ask what we can gain from change, while conservatives ask what we can lose. At every moment of crisis, this is a valuable conversation to have—if it is in fact a conversation. Otherwise it evokes a kind of madness, like talking to oneself in the subway.

Nowadays, blather rattles the land like thunder. In cabs, diners, and doctors’ waiting rooms, the din of stupid opinion yields only to the grinding of one’s teeth. But for our lightbulbs, we would seem to be entering a dark age. The noise today is relentless, enough to inspire thoughts of taking a drill to one’s eardrums. It is inescapable, this babbling rabble of 24-hour TV. Bill O’Reilly seems to be always on the verge of an aneurysm. Greta Van Susteren, a Scientologist with a questionable grasp of reality, grunts and slurs like a bartender who’s her own best customer. Nested with parrots and mockingbirds, the Capitol Building has become an echo chamber for Fox News. Senator Ted Cruz, a champion Princeton debater and a Harvard doctor of law, now sounds like Sarah Palin with more testosterone.

A Bach fugue is as trying on the hands as on the head, and if Buckley the writer and musician aspired to self-mastery, it was in the pursuit of excellence. Excellence, of course, is the antithesis of our leaders’ and pundits’ lack of seriousness, discipline, and integrity. When asked to provide a mission statement for The National Review, Buckley turned to the question of character: “The largest cultural menace in America is the conformity of the intellectual cliques which, in education as well as the arts, are out to impose upon the nation their modish fads and fallacies, and have nearly succeeded in doing so. In this cultural issue, we are, without reservations, on the side of excellence … and of honest intellectual combat (rather than conformity).”

Though some suspect Buckley of elitism, his demand for excellence simply set him against mediocrity. This is as it should be. His intellect, eloquence, and candor would be a tonic for the oafs now puffing themselves up as Republican messiahs. In its most noxious strain, their populism equates to craven demagoguery and outright philistinism. Such thinking prevents the consideration of radical, inventive, unique voices and ensures that politicians, on the right but also on the politically correct left, remain toadies to their respective orthodoxies.

A master of counterpoint, Buckley despised orthodoxy within his own movement. He spurned dogma and hewed to original principles as the need arose. The rigor of his views did not lend themselves to rigor mortis, and he often veered radically from orthodoxy in favor of the practically radical or radically practical. When entering the public sphere, he was reluctant to accept the conservative label, preferring to call himself an “individualist.” He once wrote that “intelligent deference to tradition and stability can evolve into intellectual sloth and moral fanaticism, as when conservatives simply decline to look up from dogma because the effort to raise their heads and reconsider is too great.” So he opposed the War on Drugs, its bitter financial and human costs, and supported the legalization of illicit substances. Though Libertarians cite him as a kind of hero, he rejected their desire to demolish the state, to privatize all public works, as the most ridiculous kind of utopianism. In a debate with Ron Paul on “Firing Line,” he held that “the libertarian position is discredited by a kind of reductionism that is simply incompatible with social life.”

He might say the same of his ideological heirs, on the airwaves and the National Mall, who crank their bullhorns of drivel to one hundred decibels. They spout so much sound and fury signifying nothing.