After he ended his long and storied career with CBS last Sunday with his final appearance as the host of Face the Nation, Bob Schieffer went on Fox News and spoke to Howard Kurtz. And if the old trope that a “gaffe” is when someone accidentally tells the truth, then Schieffer committed one last gaffe on his way out the door. Kurtz, king of the leading question, asked Schieffer if the media gave Barack Obama an incredibly easy ride in 2008 and Schieffer replied ” I don’t know, maybe we were not skeptical enough. It was a campaign.”

He did catch himself and quickly added that it is the role of the opponents to “make the campaign.” He said, “I think, as journalists, basically what we do is watch the campaign and report what the two sides are doing.”

Except when they’re not being “skeptical enough” or giving them an “easy ride.”

He sort of gave the game away, didn’t he? The press wasn’t skeptical enough. Of what? Has President Obama subsequently been accused of scandal? Is he corrupt? Compared to other recent administrations (ahem), the Obama White House has been downright saintly. Is he unusually unpopular? No, the country is divided along party lines; but he is just as popular with the people who voted for him as he ever was. So what should the press have been more skeptical about? It must be his policies, which apparently Howard Kurtz and Bob Schieffer don’t like and believe should have been more thoroughly challenged. That’s a long way from “We watch the campaign and report what the two sides are doing.”

Schieffer is old friends with George W. Bush and has long been presumed to lean conservative. Anyone on Fox, like Kurtz, almost certainly is. So they aren’t being particularly dishonest if they show favoritism toward Republican politicians. They have an obvious, if not overt, partisan affiliation with the GOP. Not that they admit it, of course. But at least it’s based on something substantial. If the rest of the mainstream press were outwardly motivated by ideology, we might be better off than we are. Instead, many of them seem to be motivated by an insular, careerist, petty, and somewhat puerile feedback loop. It’s not partisan or even political; it often appears from the outside to be a random decision within the herd to “prove” the media’s independence and clout and then becomes a competition within the field.

Matt Yglesias at Vox wrote yesterday about the dynamic between the press and the Clinton campaign. He pointed out that recent polling, admittedly early and without a lot of bearing on where we will be a year and half from now on election day, shows that Hillary Clinton is a very popular politician. As he points out, the Gallup poll has shown her the most admired woman in the world for the last 17 out of 18 years.

Again, this has little to do with what polls will say in 2016, but it does say something about the press in 2015 that this popularity is not just ignored when political reporters write about Clinton; from reading press coverage, you’d be surprised that anyone in America can stand the woman at all.

Yglesias gives us a couple of examples that perfectly reflect the way this is done:

For Clinton, good news is never just good news. Instead it’s an opportunity to remind the public about the media’s negative narratives about Clinton and then to muse on the fact that her ratings somehow manage to hold up despite these narratives.

Here’s how the Wall Street Journal wrote up an earlier poll showing Clinton beating all opponents:

“Hillary Clinton’s stature has been battered after more than a month of controversy over her fundraising and email practices, but support for her among Democrats remains strong and unshaken, a new Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll finds.”

And here’s how the New York Times wrote up yet another poll showing Clinton beating all opponents:

“Hillary Rodham Clinton appears to have initially weathered a barrage of news about her use of a private email account when she was secretary of state and the practices of her family’s foundation, an indication that she is starting her second presidential bid with an unusual durability among Democratic voters.”

This framing is not surprising, since, among journalists, Clinton is one of the least popular politicians. She is not forthcoming or entertaining with the press. She doesn’t offer good quotes. She doesn’t like journalists, respect what we do, or care to hide her disdain for the media.

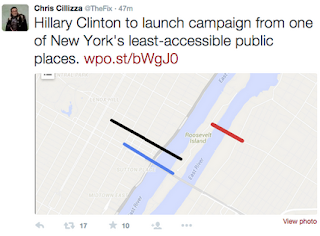

Here’s a random tweet that illustrates the political media’s framing perfectly:

That’s one way of putting it. It’s clearly supposed to tell people that Clinton doesn’t care about people. (It’s actually a beautiful spot for a campaign announcement in front of the UN, one of Eleanor Roosevelt’s personal projects. But I’m sure there’s something terrible about that as well.)

Yglesias goes on to point out that the public does not hold the press in high esteem, which is true. They do not think the press is credible and you can’t blame them. When it comes to presidential politics, I think this is mainly because the way the press covers presidential campaigns leads the average person to believe the media thinks it’s their job to decide who America’s leaders are for them, and to tell them what they should care about. When they put their thumbs on the scales as those examples above do, it’s fairly obvious that the media have decided that this person is not someone for whom the American people should have any regard. And, inevitably, what the press thinks the people should care about is different than what people actually care about. And more often than not, it turns out that the trivial “narratives” which are supposed to reveal deep character flaws, if not actual bad behavior, end up reflecting back on the press rather than the politicians.

The Clinton administration is a very good example of this. During the impeachment crisis, the media were stunned that public support for the president never wavered. In fact, his approval rating hit an all time high the week after he was impeached:

Despite the fact that he is only the second President in U.S. history to be impeached by the House of Representatives, President Bill Clinton received a 73% job approval rating from the American public this past weekend, the highest rating of his administration, and one of the higher job approval ratings given any president since the mid-1960s.

Washington columnist Sally Quinn had earlier written her famous piece about the dismay with which the political establishment, including the media, greeted the president’s popularity:

With some exceptions, the Washington Establishment is outraged by the president’s behavior in the Monica Lewinsky scandal. The polls show that a majority of Americans do not share that outrage. Around the nation, people are disgusted but want to move on; in Washington, despite Clinton’s gains with the budget and the Mideast peace talks, people want some formal acknowledgment that the president’s behavior has been unacceptable. They want this, they say, not just for the sake of the community, but for the sake of the country and the presidency as well.

She went on to interview numerous members of the press about “the disconnect” and was told that the public’s attitude was just plain wrong. The people didn’t understand the gravity of the president lying about an affair to members of the press. This was about them, you see, and that made it a national concern. It was all fatuous in the extreme, with affairs and indiscretions among powerful men being common knowledge among all these people. It was just that “getting Clinton” had become the challenge, and the more they tried to do it with their scandal mongering, the more the public sensed that it was a game and the more they liked Clinton and hated the press.

The press being popular with the public isn’t really important. In fact, if they were unpopular because they took their role as a countervailing weight against government power seriously, that would be a good thing. But that is not the case. They are unpopular because they are often fixated on elevating certain people and destroying others for capricious reasons and become obsessed with the simple challenge of doing it. And, perhaps more importantly, many of them seem to confuse what they are doing with what the public cares about.

Hillary Clinton has many flaws, like all of us, and the American people may end up deciding that her positives don’t outweigh them no matter how popular she is today. But a refusal to cater to the political press is unlikely to be among their reasons for rejecting her. They know that silly complaint doesn’t translate into a serious attempt to discern whether Clinton (or any other pol they decide needs this treatment) is a capable leader with good ideas and the temperament to be the president. It’s already obvious that this has become yet another contest among insiders to see if they can “take her down”.

She may not win, but it won’t be because she was mean to the political press corps. That’s actually a selling point. You’d think they’d have figured that out by now.