After conflict between protesters and police hurled Ferguson, Missouri, into the national spotlight last year, a federal investigation revealed that the city’s courts systematically exploited black residents through arrests and hefty fines. Sixty-seven percent of Ferguson is black, media breathlessly reported, but the presiding judge, district attorney, five of six city council members, and 50 of 53 police officers were white. Racialized policing and biased criminal justice practices made sense here. This was a story we knew how to tell.

Then there was Baltimore.

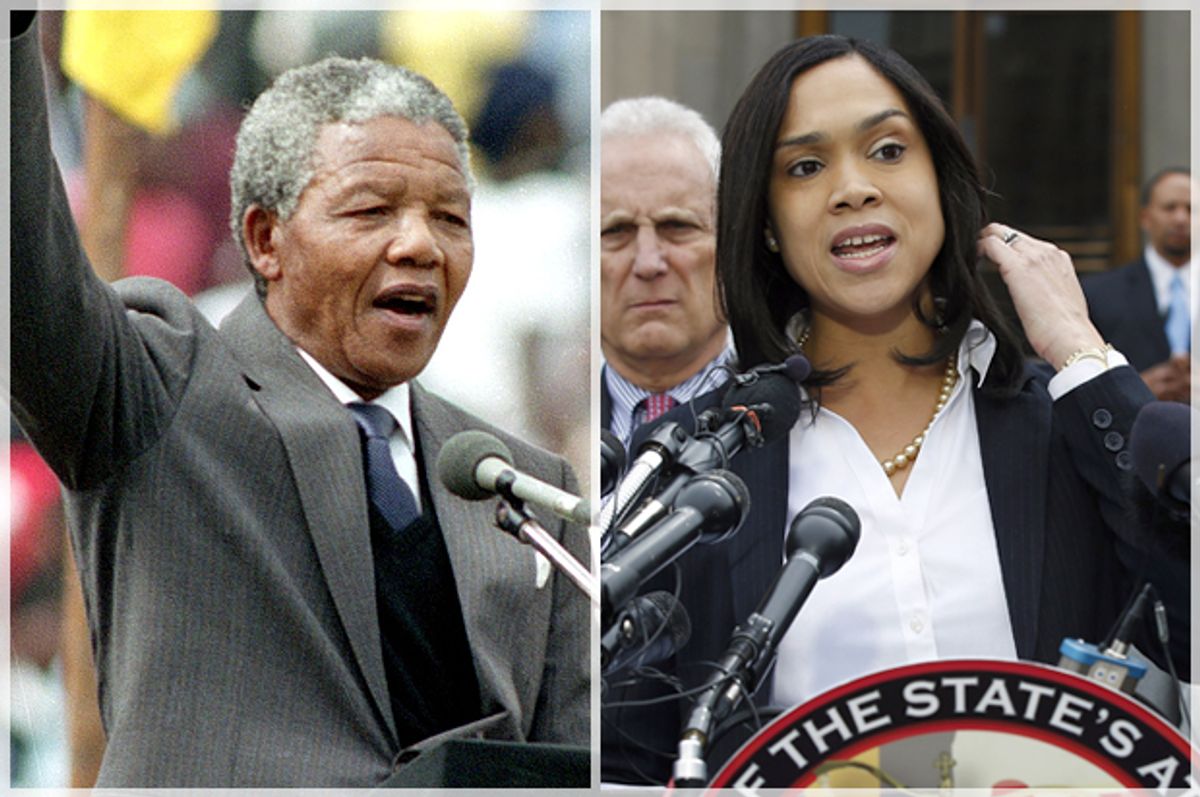

When 24-year-old Freddie Gray died on April 19, the scene was quickly dubbed “the next Ferguson.” And like Michel Brown, Gray was another unarmed young black man whose death at police hands sparked #blacklivesmatter protests, calls for accountability, and allegations of racism. Unlike Ferguson, Baltimore is a majority black city with a black mayor, a black state’s attorney, and a black police chief leading a largely black force -- where racialized poverty, racially disproportionate arrests and incarceration, and police brutality still exist. An analysis of census data ranked Baltimore among the most racially segregated cities in America in 2013, and violent policing has characterized crime control in the city for decades.

“Having black cops and black mayors doesn’t end police brutality,” Stacia Brown declared last month in the New Republic – but to some, it does prove the issue is not racial. “You can’t have racial profiling in a city that’s almost all black,” explained the mayor of Miami Gardens, Florida, when faced with troubling video evidence of targeted police harassment. Publishing the Baltimore defendants’ mugshots, Fox News agreed: “that half of the officers are black appears to dispel the notion that the death of Gray was racially motivated.”

After spending several months researching the South African criminal justice system from Johannesburg, I returned to the U.S. just in time to witness the national conversation swirling around Baltimore – and the similarities were too clear to ignore. South Africa is a majority black nation with a relatively new black leadership structure and a long history of injustice. Like South Africa, Baltimore -- and America as a whole -- is struggling to understand the difference between changing who runs a system and changing the system itself.

“The majority of the people know that this is way bigger than Freddie Gray,” said Dominic Moulden of ONE DC, a resident-led organizing collective advocating for economic and racial equity in D.C. neighborhoods. An organizer and activist for nearly 30 years, Moulden, 53, draws inspiration from the recent mass demonstrations in his native Baltimore. “This is way bigger than people just getting a house, getting a job and going to school. If we don’t deal with the economic structure and the political structure of this country, then none of this stuff will change.”

As Joel Modiri, a black law professor at Wits University in Johannesburg, told me earlier this year, “the U.S.-South Africa comparison is brilliant because it shows it’s not just a numerical thing.”

*

South Africa and the United States are undeniably different. Less than 10 percent of South Africans are white and the black-dominated African National Congress (ANC) party has held the country’s political reins since the 1994 election made Nelson Mandela president and ended the racial separation policies of apartheid. In the U.S., black people constitute just 13 percent of the population and mass incarceration is regularly critiqued as a racial issue. Far from signaling a new era of black political dominance, Barack Obama’s presidency intensified racial polarization in the nation even as he’s proved largely moderate on racial issues in both action and rhetoric.

“It seems,” said civil rights lawyer Bryan Stevenson in an appearance on the Colbert Report, “that we have a black president who isn’t allowed to talk about race because he’s a black president.”

The countries’ differences make their similar criminal justice crises striking. The United States imprisons nearly 2.3 million people, the highest prison population in the world; South Africa currently ranks 11th, and highest in Africa. Prison overcrowding plagues both systems as high prison populations continue to grow, while private prisons flourish; horrific, documented abuse runs rampant; and hollow constitutional protections provide little relief. And the two nations share a deeper bond.

Like the U.S., South Africa was founded upon philosophies of racial difference that shaped and molded social and economic relations for generations, and used the criminal justice system as a tool of enforcement. Like the U.S., South Africa long relied on law, police, arrests and prisons to enforce a strict system of racial injustice. And like the U.S., South Africa purports to stand as a model of what it means to “overcome” while struggling to create a criminal justice system worthy of its ideals.

“There was a time when we all read Martin Luther King, two pages a night, and then you had to pass it on because if you were caught with that book it was prison,” Commissioner Danny Titus of the South African Human Rights Commission recalled. “It meant a lot, following things in Alabama, and Montgomery, and all those kinds of things, because it was very much comparable in the sense of racial discrimination. Now, South Africa has transformed the criminal justice system in terms of racial presence. I don’t think you have that at that stage or that level in the United States.”

Speaking nationally, Titus is right – but in some urban centers, like Baltimore, where there has been a transformation from white leadership to black, lingering legacies of racial injustice remain and their persistence is telling.

*

Days after State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby announced charges in Freddie Gray’s death, a local activist named Dayvon Love spoke with with Melissa Harris-Perry on MSNBC. “I think Baltimore shows the sophistication of white supremacy and how it operates,” explained Love, 28, co-founder of the grass-roots advocacy organization Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle. “How it takes black figures, puts them in institutional positions to give the veneer of justice, when really the same institutional arrangement exists.”

Watching the Baltimore unrest from the other side of the world, South Africa’s Daily Maverick reached a similar diagnosis:

Despite the city being largely in the hands of a new-ish black political elite, on-the-ground policing has remained a problem for Baltimore. Old patterns of policing black neighborhoods have remained in the mode of what some have taken to describing as being in the style of an army moving in hostile territory – despite the fact that the police force itself also became increasingly African American in its personnel. . . . Taken together, many in Baltimore’s African American population could easily see their present and future circumstances as hemmed in by the lack of real prospects for employment, under the watch of a police force that treated them as the enemy, and their lack of any “agency” to leverage the political power structures of the city to their economic and social advantage despite the altered racial demographics.

Love also challenged the narrative of monolithic black leadership. Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake was a mainstream party candidate, he explained, while State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby was an underdog who garnered enough grass-roots support to beat an incumbent with more resources.

Turnout rates were similar in both the primary election that Rawlings-Blake won in 2011 and in Mosby’s 2014 primary win, but results do suggest that the two candidates, both black women, rode significantly different constituencies into office. In the first ward, for example, where 85 percent of the more than 12,000 residents are white, Rawlings-Blake won about 45 percent of the vote while Mosby won just 25 percent less than three years later. In the seventh ward, where 93 percent of the 10,000 residents are black, the advantage was flipped: Mosby carried the ward with 67 percent of the vote in 2014 while Rawlings-Blake won less than half in 2011.

Announcing her candidacy in June 2013, Mosby declared it her aim “to change the culture of distrust and bring all parts of the community together – the judges, the police, the people, the state’s attorney.” Black Baltimore rallied around her vision but South Africa gives reason to question whether old tools can be put to new purpose.

*

South African apartheid institutionalized whites’ political, social and economic dominance over a country where they were a ruling minority. With laws that strictly classified citizens by race and mandated separation between them, apartheid solidified a strict hierarchy that relegated native black Africans to a heavily regulated bottom caste denied free movement and association, education and social equality. For more than 40 years the harsh system brutally suppressed domestic dissent. As apartheid took its last gasps in the 1980s, South Africa had the highest incarceration rate in the world, imprisoning 373 people per 100,000 in 1989, many for acts of political resistance.

Commissioner Danny Titus began his career in South Africa’s National Prosecuting Authority in 1983, and in an interview in his Johannesburg office recalled the palpable racialization of a system that then had no place for “colored” prosecutors. “We literally had to fight them to get in. And when you got in, it was really entering a white world, because [whites] dominated the criminal justice system.”

Last year, South Africa marked 20 years since the “transition to democracy,” but high rates of violent crime, economic inequality, and xenophobic violence among the poor complicates the national narrative of successful revolution.

A black, 24-year-old law professor, and one of the nation’s only critical race theorists, Joel Modiri speaks from a different generation. Growing up in Pretoria, South Africa’s administrative capital, he was confused by the gap between the national narrative of freedom and the reality of continued inequality. “The horror of the black condition is still visible today – almost as visible as it was back then,” he explains. “This thing of apartheid is not over, and we’re missing something in the story if we think we are dealing with just leftovers, just tying up a few loose ends and then we can all move on.”

Though the vast majority of lawmakers, judges and prison leaders are now black, apartheid’s end did not begin a national project to dismantle and rebuild a system for responding to crime. Power changed hands but continued on the same track. Mandatory minimum sentencing laws that flourished in the U.S. beginning in the 1980s were embraced by South Africa’s democratic government post-1994 as a response to growing poverty and crime, and the number of South African prisoners serving life sentences has increased by nearly 3,000 percent. Lengthy and widespread imprisonment, a tool whites first embraced as a means of exploiting and controlling the nation’s black masses, is now wielded by the nation’s black leaders.

“The history was cast as one of spectacular violence by individuals, so we were being told to see that the institutions were fine, but there were bad people using them for bad purposes,” reflects Modiri. “This idea of punishment, of zero tolerance, of just deserts, stayed. So what we have in South Africa is apartheid in blackface.”

*

In pursuing charges and securing indictments for the death of Freddie Gray, State’s Attorney Mosby did what officials in Ferguson, Long Island, Cleveland and elsewhere could not or would not do. Her race, background, campaign platform and accountability to a particular constituency surely influenced that outcome – but could not transform the limits of her office any more than black political power alone has derailed a tradition of inhumane crime control in South Africa.

A Mississippi official in 1865 looked upon slavery’s demise in this country and reasoned, “Emancipation will require a system of prisons.” The complicated web of discriminatory laws, convict leasing and disenfranchisement that reigned for the next century saddled black people with abuse and inequality, while promoting prisons and punishment as legitimate means of controlling the response. The civil rights movement led to landmark federal legislation in voting and public access laws, but did little to challenge courts, prisons and the tolerance for black incarceration. Today, one in nine black American men is incarcerated; one in three is in jail, in prison or on probation or parole; and the system of prisons is alive and well.

“Until you get these people to respect black bodies, you’re not going to change anything,” said Moulden. “But you’re going to get fooled by these individual legal and judicial rulings, and you’re still going to have black people practicing white supremacy through the police state.”

In 2012, Baltimore reduced its $10 million recreation budget by closing 20 recreation centers, while spending more than $300 million on law enforcement programs – up from $182 million in 1991. Last September, the Baltimore Sun revealed that more than 100 people had successfully sued the city’s police department for brutality, civil rights violations and wrongful death in the past four years.

“To the rank and file officers of the Baltimore City Police Department,” Mosby said near the close of her press conference on May 2, “please know that these accusations against these six officers are not an indictment of the entire force.”

Whatever the fate of these officers, whatever the race of their prosecutor and mayor and city council, this system will never put itself on trial – and that should be enough to shake our faith in it.

Shares