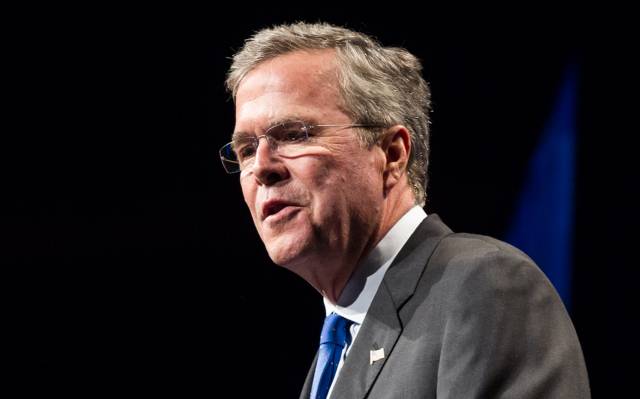

After spending a half-year or so charging wealthy donors from Wall Street to Silicon Valley remarkable amounts of money — sometimes as much as $100,000 — to ask him questions, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush now says he’s ready to finally make his presidential campaign official. He’s even got a whole “new” logo and everything, one that conveniently omits his troublesome surname. Yes, we’re in for at least another good 10 months or so of talking about a would-be President Bush. I’m sure you can’t wait.

There will be plenty of time for plenty of profiles of Jeb. If there’s anything especially interesting about the man that we don’t know already — if he, too, grew up with a Romney-esque fixation on the length of his classmates’ hair, for example — we’ll know soon enough. In all honesty, though, I’ve never found Jeb to be an especially compelling figure; he lacks his ex-president brother’s pathos and his ex-president father’s anachronistic noblesse oblige. Indeed, from all the talk his boosters have of his being the “grown-up” among the GOP contenders, his staidness seems to be part of his appeal.

Still, although Bush-the-man may be a bit dull, his White House strategy — particularly his decision to outsource many traditional campaign activities to a super PAC — is on the cutting edge. In fact, even if Jeb falls short of his goal and does not become the third-straight Republican president named Bush, it’s possible that his fulsome embrace of the post-Citizens United era of campaign finance will be a significant legacy. Win or lose, Bush 2016 will have a lasting influence on U.S. politics. It just might not be the kind Bush hopes.

At this point, you’re probably familiar with the odd quirk presidential candidates have of not admitting they’re campaigning, regardless of how obvious it is. Many candidates do this, largely because it allows them to fundraise without as much oversight from the Federal Election Commission and because it allows their donors evade the $2,700 limit on individual contributions. Yet just as his brother took the jingoist and deficit-ballooning habits of President Reagan and put them on steroids, Bush has taken a flimsy regulatory status quo and, with the help of the Supreme Court as well as his trusted “Right to Rise” super PAC, essentially burnt it to a crisp.

As law professor and campaign finance expert Richard L. Hasen wrote in Slate back in April, Bush’s unwillingness to even admit he was exploring a run, when coupled with his decision to have a super PAC run much of his campaign, “has allowed him to undermine one of the last rules in campaign finance law” we have left. Not only has he been able to keep asking donors to send his super PAC seven-figure checks, but he’s also made clear that any separation between his official campaign and his super PAC will be nominal at best. So far, this has worked out well for Bush, who reportedly has already raised nearly $100 million. But by implicitly acknowledging that his super PAC won’t really be “independent,” he’s also taken an axe to one of the Citizens United majority ruling’s foundational arguments.

To be fair to Bush, that argument was always absurd on its face. It held that unlimited contributions to “outside” groups like super PACs would not only not lead to corruption, but that they wouldn’t even lead to the perception of corruption — because these groups would operate independently. In other words, if Sheldon Adelson wants to give, say, Sen. Marco Rubio’s super PAC $10 million, there should be no worries about corruption so long as the people running the super PAC and his campaign never communicate. Most people outside the Federalist Society fantasyland of Justice Anthony Kennedy’s head immediately knew campaigns would find a way to sneak around this.

By announcing that his super PAC will handle much of the campaign’s nuts-and-bolts, Bush made clear to donors that they need not worry about their money going to waste. Because he ostensibly hadn’t decided yet whether to run for president, he could solicit six- and seven-figure donations; and because he was outsourcing to his super PAC, donors knew that giving “Right to Rise” $100,000 now was tantamount to giving $100,000 to the Jeb Bush campaign. For those worried that folks like the Koch brothers had insufficient influence over presidential candidates, Bush’s new model was a godsend. Better still, since super PACs don’t have to disclose their donors’ names, this could all be accomplished without having to worry about public condemnation.

That’s all coming to an end this week, however, with Bush’s announcing himself as an official candidate. The super PACs will keep hoovering-up money, of course, but they’ll no longer be able to use the starpower of the candidate to open donors’ wallets. When it comes to unleashing such an all-out push for donations, they’ll be forced to settle for the $100 million or so Bush has allegedly raised already, the poor things. In the long run, though, the brazenness of Bush’s strategy may end doing plutocratic-friendly politicians like him more harm than good. Because while he takes the money and runs, what he leaves behind is undeniable proof that, even on its own terms, the post-Citizens United system of campaign finance simply doesn’t work.