At 9:44 p.m. on July 27, 1953, Private First Class Harold B. Smith had just sixteen more minutes of the Korean War to survive before the cease-fire came into effect at 10:00 p.m. You can imagine this twenty-one-year old marine from Illinois, out on combat patrol that evening, looking at his watch. Smith didn’t have to be in Korea. He had already served his time in the Philippines. But he volunteered for the fight. He also didn’t have to be on patrol that evening. But he offered to take the place of another guy who went out two nights before.

Suddenly, Smith tripped a land mine and was fatally wounded. “I was looking directly at him when I heard the pop and saw the flash,” recalled a fellow marine. “The explosion was followed by a terrible scream that was heard probably a mile away.” Another soldier said, “I was preparing to fire a white star cluster to signal the armistice when his body was brought in.”

Twenty-two years later, on April 29, 1975, Lance Corporal Darwin Judge and Corporal Charles McMahon were marine guards near an air base outside Saigon in South Vietnam. Judge was an Iowa boy and a gifted woodworker. He once built a grandfather clock that still kept time decades later. His buddy, McMahon, from Woburn, Massachusetts, was a natural leader. “He loved the Marines as much as anybody I ever saw in the Marines,” said one friend.

The two men had only been in South Vietnam for a few days. They were part of a small U.S. security force that remained after the main American withdrawal in 1973. McMahon and Judge arrived just in time for the military endgame, as North Vietnamese troops bore down on Saigon. McMahon mailed his mother a postcard: “After this duty, they may send us home for a while…. I’ll try to write when I have time and don’t worry Ma!!!!”

At 4:00 a.m. on April 29, a Communist rocket struck Judge and McMahon’s position and the two men died instantly. In the chaos of the final American exit from South Vietnam, with helicopters desperately rescuing people from rooftops, McMahon and Judge’s bodies were accidentally left behind. It took months to negotiate their return.

On the early evening of November 14, 2011, Army Specialist David Hickman was traveling in an armored truck through Baghdad. Hickman, from North Carolina, had been in ninth grade when the Iraq War started in 2003. He was a natural athlete with a black belt in Tae Kwon Do. “He always seemed like Superman,” said one of his friends.

A massive explosion ripped into Hickman’s truck. It was a roadside bomb—the signature weapon of the Iraqi insurgents. Hickman was grievously wounded. The next day, just before midnight, the army visited Hickman’s parents in North Carolina to tell them their son was dead.

Smith, Judge, McMahon, and Hickman were the final American combat fatalities in Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq, respectively. An unknown soldier will have the same fate in Afghanistan. These men are the nation’s last full measure of devotion. The final casualty in war is uniquely poignant. It highlights the individual human price of conflict. It represents the aggravated cruelty of near survival. It has all the random arbitrariness of a lottery. The Soviet-made 122 mm rocket that killed Judge and McMahon in 1975 was famously inaccurate. It could have landed anywhere in the vicinity. But it fell just a few feet from the marines. Sergeant Kevin Maloney found their bodies and wondered, “Why them and not me?”

The closing casualty has particular resonance in a war without victory. Who could expect anyone to be the final soldier, as the saying went in Korea, to die for a tie? Or even worse, as former navy lieutenant John Kerry remarked during congressional testimony on Vietnam in 1971, “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?” One of David Hickman’s buddies said about Iraq, “I’m just sad, and pray that my best friend didn’t lay down his life for nothing.”

Most of all, the final casualty underscores the value of ending a failing conflict. If we could have resolved the wars in Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq earlier—even just a few minutes earlier— Smith, Judge, McMahon, and Hickman’s lives would have been the first to be spared.

And now we can imagine Smith, Judge, McMahon, and Hickman standing in three great lines of the American dead from these wars. Arranged single file in the order they fell in battle, the columns stretch back like solemn processions. As we conclude the violence a day earlier, a month earlier, or a year earlier, more and more of these men and women are spared.

How can we end a deteriorating war? Is it possible to withdraw from a stalemated or losing campaign without abandoning our interests or betraying our values? When military victory is no longer possible, can we escape with a draw or a minor failure rather than endure a complete debacle? In other words, is there a right way to lose a war?

Today, these are critical questions because we live in an age of unwinnable wars, where decisive triumph has proved to be a pipe dream. Since 1945, the United States has suffered a string of military stalemates and defeats in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Time and again, in the face of a worsening campaign, Washington struggled to cut the nation’s losses and find an honorable peace. Following battlefield failure, the United States groped for the exit like a man cast in darkness. We’re good at getting in but bad at getting out. Or, as Barack Obama put it in 2014, “I think Americans have learned that it’s harder to end wars than it is to begin them.”

In Korea, we spent two years negotiating a truce, even as brutal attritional fighting continued. In Vietnam, peace talks lasted for five years, with little to show for it. It took twenty-one days to capture Baghdad in 2003 and 3,174 days to leave Baghdad. We seized Kabul in November 2001 — and we’re still there. The price for these failed exit strategies was paid in American lives, domestic discord, crippled presidencies, and devastation for the local people.

In an era when American wars usually end in regret, we need to think seriously about military failure: why it happens and what we can do about it.

But before we consider how to get out of a military quagmire, we need to understand why we get lured into the morass in the first place.

The Golden Age

On June 5, 1944, the eve of D-day, U.S. general George S. Patton strode onto a makeshift stage in southern England to address thousands of American soldiers. “Americans play to win all of the time,” said Patton. “I wouldn’t give a hoot in hell for a man who lost and laughed. That’s why Americans have never lost nor will ever lose a war, for the very idea of losing is hateful to an American.”

It was the golden age of American warfare. Patton could look back on a century of U.S. victories in major wars. Victory means that Washington achieved its core aims with a favorable ratio of costs and benefits. Major war means an operation where the United States deployed over fifty thousand troops and there were at least one thousand battle deaths on all sides.

The golden age began in 1846, when the United States locked horns with Mexico. For eighteen months, the United States won battle after battle. In the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Washington paid $15 million to Mexico, and assumed several million dollars’ worth of Mexican debts, in return for seizing about half of Mexico’s territory and creating the modern American Southwest. Northern Whigs recoiled at the acquisitive U.S. objectives. But the Mexican-American War was popular with most Americans, especially Democrats in the South and West, who believed in the nation’s Manifest Destiny to expand from sea to shining sea.

Two decades later, the Civil War was widely seen in the North as a heroic struggle for Union and emancipation, which saved, in Lincoln’s words, “the last best hope of earth.”13 The nation emerged through a hellfire of fratricidal slaughter to preserve the United States, in the words of a sergeant from Indiana, as “the beacon light of liberty & freedom to the human race.”

The Spanish-American War of 1898 heralded the emergence of the United States as a new great power. The campaign was a wildly popular adventure where Washington brushed aside Spanish forces, freed Cuba from Madrid’s grasp, and annexed Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. Theodore Roosevelt became a national celebrity after he charged up San Juan Heights accompanied by the Rough Riders and an embedded journalist. “Up, up they went in the face of death, men dropping from the ranks at every step….Roosevelt sat erect on his horse, holding his sword and shouting for his men to follow him.”

Not every U.S. war in this era was a clear-cut triumph. Following the Spanish-American War, for example, the United States suppressed a nationalist insurgency in the Philippines at a high cost of over four thousand American dead, and over two hundred thousand Filipino civilian fatalities—mostly from famine and disease related to the war. It was a harbinger of the darker era of warfare to come.

But the United States soon returned to the path of victory. The country was a late entrant into World War I, joining the fray in 1917, three years after the opening salvos. U.S. intervention proved decisive in breaking the stalemate and defeating Germany. When the armistice was finally reached in 1918, the United States was clothed in immense physical power and moral prestige.

In 1944, as Patton addressed the troops, the glorious era was about to reach its pinnacle. “By God,” he said, looking ahead to D-day, “I actually pity those poor sons of bitches we are going up against.” World War II passed into history as the good war: a struggle of moral clarity and total commitment against the architects of the Holocaust. The campaign was a testament to the valor-studded splendor of American warfare.

The century from 1846 to 1945 was defined mainly by conventional interstate wars, where the United States fought enemy countries on a clear battlefield. Our army met their army, we won decisively, and then we imposed our terms. World War II epitomized America’s talent for overwhelming opposing states with mass production, logistics, and technology. At its peak capacity, American industry churned out a new aircraft every five minutes and forty-five seconds. The atom bomb was the ultimate expression of American technological prowess. “To say that everything burned is not enough,” recalled one witness at Nagasaki. “It seemed as if the earth itself emitted fire and smoke, flames that writhed up and erupted from underground.”

The price of military triumph was often immense. In the Civil War alone, there were around 750,000 American fatalities — more than the deaths in every other U.S. war combined. The journalist Ambrose Bierce wrote about one soldier who fell at Shiloh in 1862. He had been “a fine giant in his time.” But now he “lay face upward, taking in his breath in convulsive, rattling snorts, and blowing it out in sputters of froth which crawled creamily down his cheeks, piling itself alongside his neck and ears.”

Despite the sacrifice, from the 1840s onward, Americans consistently strode into what Winston Churchill called the “broad sunlit uplands” of victory. The costs of conflict were staggering, but so were the benefits. The Civil War saved the Union and emancipated the slaves. World War II ensured the survival of liberal democracy in Western Europe. If we classify the Philippine campaign as a draw, or an ambiguous outcome, the overall tally comes to five victories, one draw, and no defeats. For Americans, golden-age conflicts became the model of what war ought to look like.

The Dark Age

And then, all of a sudden, we stopped winning major wars. The end of World War II was a turning point in America’s experience of conflict. The golden age faded into the past, and a new dark age of American warfare emerged. Since 1945, Americans have experienced little except military frustration, stalemate, and loss.

The martial dusk fell in June 1950, when Communist North Korea invaded non-Communist South Korea. Fearing that the Soviet Union and China were set on world domination, Washington led an international coalition to aid Seoul. The campaign began brightly, as U.S. forces defended South Korea from invasion, and then took the offensive to roll back communism in the North. American soldiers captured Pyongyang and took photos of each other sitting behind Kim Il Sung’s massive desk.

In November 1950, however, China unexpectedly intervened with hundreds of thousands of troops, landing a hammer blow on American forces. In one of the biggest battlefield defeats in American history, U.S. troops retreated south through an icy wasteland. The fighting in Korea descended into a grim stalemate until a truce was finally reached in 1953, at a cost of nearly 37,000 American lives. For a nation used to golden victories, Korea was a confusing and wearying experience—in the words of cartoonist Bill Mauldin, “a slow, grinding, lonely, bitched-up war.”

Worse was to follow. In 1965, South Vietnam was crumbling in the face of a Communist insurgency. President Lyndon Johnson sent half a million American soldiers into what he called “that bitch of a war.” Trying to resuscitate South Vietnam, the United States found itself chained to a corpse. For the first time in American history, the nation faced outright military defeat — and, most shockingly, against North Vietnam, a “raggedy-ass little fourth-rate country,” as LBJ put it.

Despite the deaths of 58,000 Americans, South Vietnam still fell to communism. The war sapped U.S. resources, divided American society, deepened popular distrust of government, eroded the nation’s self-identity as a vessel of goodness in the world, damaged America’s global image, and helped to destroy the careers of two presidents—Johnson and Richard Nixon. The American army that went to Vietnam was more impressively equipped than at the start of any previous war. The American army that left Vietnam was unraveling, as discipline deteriorated and drug use became rampant. Henry Kissinger, the secretary of state from 1973 to 1977, said, “We should never have been there at all.”

The 1991 Gulf War was a successful military operation, where the United States liberated Kuwait from Saddam Hussein’s grip at low military cost. A quarter of a million American soldiers launched a surprise left hook assault across the Iraqi desert, and within 100 hours the ground campaign was over. The U.S. Army’s official history of the war described “the transformation of the American Army from disillusionment and anguish in Vietnam to confidence and certain victory in Desert Storm.”

The Gulf War was tarnished, however — not by what we did, but by what we didn’t do. The White House portrayed the war as a morality tale, and cast Saddam Hussein as the second incarnation of Hitler. This story is meant to end with the overthrow of the ruthless tyrant. But President George H. W. Bush brought the curtain down before the final act by refusing to march on Baghdad. It was a wise decision. Bush’s own son might attest to the dangers of seeing the performance through to regime change and beyond.

For many Americans, however, the outcome of the Gulf War felt hollow and unsatisfying. Polls showed that the American public didn’t think the campaign was a victory—because Saddam remained in power. It was a war from the dark age rather than the golden age. As Bush wrote in his diary, “It hasn’t been a clean end — there is no battleship Missouri surrender. This is what’s missing to make this akin to WWII, to separate Kuwait from Korea and Vietnam.”

A decade later, the United States regressed back to disillusionment and anguish. Harold Macmillan, the British prime minister from 1957 to 1963, reportedly said, “Rule number one in politics: never invade Afghanistan.” In October 2001, the United States swaggered into this harsh and beautiful land. Within two months, the Taliban were routed from Kabul and fled south toward the Pakistan border.

But the war was not over. The Taliban recovered and escalated their attacks, setting the stage for today’s stalemated conflict. The United States and its allies have largely rid Afghanistan of Al Qaeda and established a range of health and education services. The Afghan election of 2014 went surprisingly smoothly. The ink-stained finger was a symbol of defiance from those who voted.

But after a dozen years of fighting against a resilient insurgency, with over two thousand Americans killed and twenty thousand wounded, and the expenditure of over $600 billion, the campaign is too costly to be considered a success. Today, no one is talking about victory. Instead, many Afghans are warily positioning themselves for the post-American era and the possibility of deepening civil war. In 2014, as the bulk of U.S. forces prepared to leave the country, the UN reported that Afghan civilian deaths and injuries had jumped 24 percent from the previous year. Meanwhile, one poll found that only 17 percent of Americans supported the campaign in Afghanistan—making it the least popular war in U.S. history.

An even bleaker tale played out in Iraq. On March 20, 2003, America’s “shock and awe” bombardment lit up the sky in Baghdad, as President George W. Bush declared, “We will accept no outcome but victory.” After Saddam Hussein was toppled, however, the mission degenerated into America’s fourth troubled war since 1945. Regime change triggered the collapse of civil government and widespread unrest, involving Saddam loyalists, sectarian groups, and foreign jihadists.

Each morning, dawn’s early light revealed car-bomb smoke drifting across Baghdad and a harvest of hooded bodies—a grim installment toward the overall tally of one hundred thousand civilian deaths. In his novel, The Yellow Birds, Iraq War veteran Kevin Powers described the pointless grind in Iraq: “We’d go back into a city that had fought this battle yearly; a slow, bloody parade in fall to mark the change of season.” In 2007, the surge of American troops helped pull Iraq back from the brink of catastrophe. But the balance sheet from the war remained steeply negative. Al Qaeda claimed a new battlefield, Iran was strengthened by the removal of its nemesis, Saddam Hussein, anti-Americanism surged, 4,500 U.S. troops were killed, 30,000 Americans were injured, and more than one trillion dollars was expended.

Zbigniew Brzezinski, the national security advisor to President Jimmy Carter, told me, “The Iraq War was unnecessary, self-damaging, demoralizing, delegitimizing and governed primarily by simplistic military assumptions that didn’t take into account the regional mosaic in which Iraq operates and the internal mosaic inside Iraq.”

The U.S. record in major wars since 1945 is one success (the Gulf War), two stalemates or draws (Korea and Afghanistan), and two losses (Vietnam and Iraq). In terms of victory, we’ve gone from five-for-six in the golden age to one-for-five in the dark age. Even the win in the Gulf has an asterisk because many Americans feel ambivalent about the result.

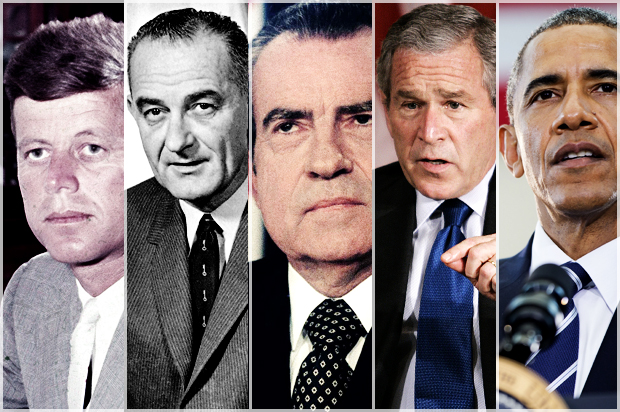

The dark age is a time of protracted fighting, featuring the three longest wars in American history (Afghanistan, Iraq, and Vietnam). It’s a time when the ultimate price of conflict is usually far higher than Americans would have accepted at the start. It’s a time when wars are synonymous with individual presidents rather than with the country as a whole—Truman’s war, LBJ’s war, Nixon’s war, Bush’s war, Obama’s war—as we blame the White House for a divisive adventure. It’s a time when military heroes are thin on the ground. It’s a time when movies and novels about war describe political conspiracy and futile struggle. It’s a time when the signature illness for veterans is post-traumatic stress disorder. It’s a time when the most resonant images of conflict are children napalmed, helicopters rescuing Americans and Vietnamese from rooftops, and intertwined naked bodies at Abu Ghraib. It’s a time when Walter Cronkite’s famous summary of Vietnam in 1968, “we are mired in stalemate,” provides an apt motif.

The dark age is a far cry from the “Veni, vidi, vici” of the golden age. Like Joe DiMaggio, victory in war seems like the relic of a bygone era. Why do we keep struggling on the battlefield? There are always unique reasons why wars deteriorate. Human error or simple bad luck may derail a campaign. But such an abrupt reversal in the nation’s military fortunes calls for a deeper explanation. Americans didn’t suddenly become less competent or brave after 1945. So what did change?

To find out the answer, let’s turn the clock back two thousand years.

Excerpted from “The Right Way to Lose a War: America in an Age of Unwinnable Conflicts” by Dominic Turner. Published by Little, Brown and Co. Copyright 2015 by Dominic Brown. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.