A few weeks away from turning 34, I like to think I’m still young. This, typically, is a wish for more time, or the hope that more time remains–time for me to do necessary work, or time for me to waste now with some left to spare for that same necessary work. This belief that I’m still young rarely comes from a position of perspective. In that sense, I feel old, aged exponentially over the last 12 months. Perhaps that’s fatigue talking, the exhaustion akin to seeing people who look like me–women and children and men–brutalized and jailed and, in some cases, murdered. Talking and writing about it has become tiresome. Still, a conversation is necessary, depending on who’s conversing, and who’s listening.

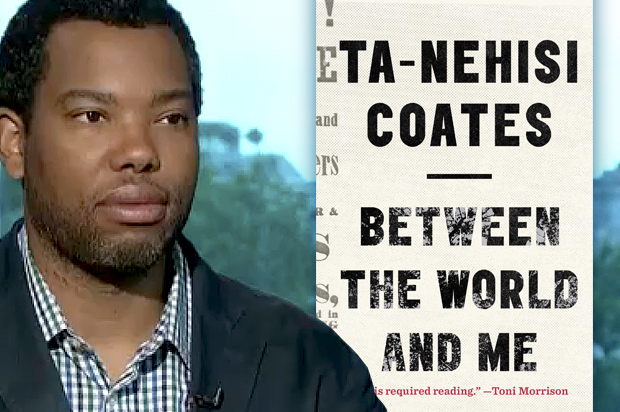

“Between the World and Me,” the new book by Ta-Nehisi Coates, attempts a conversation–a frank one, to be honest–on race relations in the United States or, perhaps more accurately, attempts to shed light, once again, on what it means to be a black man in today’s “post-racial” America. A notable, prolific and often nuanced columnist for the Atlantic, Coates has arrived at a place and moment where his brand of writing–balanced and earnest, but rarely sentimental or maudlin–may fill a void left behind by James Baldwin, if one were to believe Nobel laureate Toni Morrison’s glowing blurb for the book.

This conversation occurs “once again” because “Between the World and Me” doesn’t necessarily tread new ground. The slim book, at only 152 pages, modernizes or refreshes the type of essay one would find in Baldwin’s oeuvre, particularly those that comprise the stunning and expansive essay collection “The Price of the Ticket.” “Between the World and Me,” then, continues the Baldwin tradition of raw facts and a seething rage, controlled and harnessed to produce arguments that stand on their own, and stand on reality, avoiding melodramatic prose that seeks sympathy over comprehension.

That Coates’ book is addressed to his son doesn’t betray this lack of sentimentality. It adds a human element to topics–the transatlantic slave trade, police brutality, white supremacy buoyed by anti-blackness–that are rife with humans, but are often spoken or written about as though they were amorphous blobs of flesh or, as Coates notes in “Between the World and Me,” natural forces above any one human, and above any human law or sense of morality. These topics were laws, policies and directives manned by people, inflicted upon people, absent any divine edict passed down by a god but, rather, the system of beliefs held by people, by men and women, executed against men and women.

“No one would be brought to account for this destruction, because my death would not be the fault of any human but the fault of some unfortunate but immutable fact of ‘race,’ imposed upon an innocent country by the inscrutable judgment of invisible gods. The earthquake cannot be subpoenaed. The typhoon will not bend under indictment.”

Coates writes in another section, “The enslaved were not bricks in your road, and their lives were not chapters in your redemptive history. They were people turned to fuel for the American machine. Enslavement was not destined to end, and it is wrong to proclaim our present circumstance—no matter how improved—as the redemption for the lives of people who never asked for the posthumous, untouchable glory of dying for their children.”

Baldwin, at least in his nonfiction, was anything but sentimental. Baldwin’s essays were dispatches from a viewpoint above the fray; not that he avoided conflict, but there was always a certain height to his essays. Baldwin bore witness, and used the essay to document the sights, the connections, he observed. Coates has a similar height and perspective to his work, both in his individual columns and here again in “Between the World and Me.”

And like Baldwin, Coates often views the landscape with a wide lens, touching on specific moments–the murder of Mike Brown, for example–to bolster a larger argument, a grand theory of anti-blackness. This theory is devoid of sentimentality, of religious platitudes and wishful thinking. From Coates’ point of view, the world–and these brief, individual lives we have–is all about flesh and bone. Our bodies: who owns them, who controls them, who decides where they live and work, who gets to break and rape and destroy them, who gets away with their destruction, and who profits from it all.

The narrative arc, the structure, of “Between the World and Me,” is noteworthy. Composed of three parts, the book is, in effect, one essay broken up, more for the readers than anyone else. The book opens, eases the reader in with memoir, with memory shaded by time, by the distance of Coates’ 40 years. From glimpses into his childhood to his formative years at Howard University, Coates uses his past not as a mirror or portal to his son’s eventual future, but as a reminder that the person Coates has become is as much about the people he has met as the decisions he has made.

Using the life and violent death of fellow Howard student Prince Jones, Coates places a face, a name, to yet another body destroyed by the hand of a police officer. And in invoking Jones’ name and body and life, Coates reminds the reader—and his son—that our lives are shaped just as much by the void left behind from a body taken, as much as our lives are enriched by those we love and who love us in return.

Again, the book is addressed to Coates’ son, Samori, and if you read the book with his son in mind–that is, as a letter or one-sided conversation between father and child, “Between the World and Me” doesn’t implode or fray at the edges. Still, one has to wonder if addressing the book to his son was the point from the very beginning, or if it was a technical and stylistic choice, one that deploys the thinnest of veils to conceal, and speak to, another audience: white people. A head-on strategy would perhaps prove fruitless, or could be easily dispensed with a wave of the privileged white hand who is, perhaps, tired of feeling guilty for having (but never so tired as to relinquishing) said privilege.

Speaking–or writing–truth to power only works if you can grab the attention of those in power. Coates, like Baldwin, centers his narrative, his theory, for lack of a better word, in blackness, albeit from a wholly male perspective. An unfortunate weakness in Baldwin’s otherwise searing prose was in its lack of inclusion of black women. Put another way, whether Baldwin mentioned a black woman or not in a given essay, black women’s specific voices, and the acts of violence inflicted upon them, rarely made their way into Baldwin’s work; how can a problem be solved if it’s never addressed?

A treatise on the state of black life in America, in all its various iterations, is hardly conclusive, or even inclusive, if one-half of the population isn’t centered alongside the men. “Between The World and Me” suffers from the same blind spot. Maybe it could be excused–maybe–by the explanation that the book, on its face, is in fact addressed from father to son, from man to boy on the cusp of manhood. But then the book’s intended target, Coates’s son, is reduced to a mere loophole for the continued erasure, and decentralization, of black women from larger conversations regarding black life, black history, and the black future. It is lamentable, to put it mildly, and removing the blind spot can do nothing but improve upon, and strengthen, this theory, this work and works like it.

Blind spot notwithstanding, Coates does write truth to power, as though he were speaking loudly enough to his son so others–white people–can overhear. Coates deconstructs whiteness, and white supremacy, with a succinct, even prose that almost makes the hideous nature of anti-blackness seem banal:

“They have forgotten the scale of theft that enriched them in slavery; the terror that allowed them, for a century, to pilfer the vote; the segregationist policy that gave them their suburbs. They have forgotten, because to remember would tumble them out of the beautiful Dream and force them to live down here with us, down here in the world. I am convinced that the Dreamers, at least the Dreamers of today, would rather live white than live free.”

Cynicism aside, there are moments in “Between the World and Me” where Coates speaks directly to his son. In these moments, Coates reveals himself as a father who, acknowledging the hard, often violent upbringing under his own parents, knows he has his failures as a parent, who could stand to be better in certain areas of his teenage son’s development. Moreover, there is hardness to Coates’ approach to his son, a hardness born out of survival, a hardness passed down from generation to generation: “I did not want to raise you in fear or false memory. I did not want you forced to mask your joys and bind your eyes. What I wanted for you was to grow into consciousness. I resolved to hide nothing from you.”

Near the end, Coates writes, “Your hopes—your dreams, if you will—leave me with an array of warring emotions. I am so very proud of you—your openness, your ambition, your aggression, your intelligence. My job, in the little time we have left together, is to match that intelligence with wisdom.” It is toward the end of the book that Coates’ voice, relative to his son, strengthens.

There is, beneath the facts, beneath the physicality of black life, a hint of desperation, but one born out of love, a palatable love for a son who Coates knows he can only protect for so long, with only so many tools. “Between the World and Me,” then, changes texture ever so slightly, its prose becoming as emotional as Coates will allow it. Again, never sentimental, but keenly aware of the violence that potentially awaits his son’s black body, Coates’ cool, measured words belie a profound terror understood all too well for centuries.