On Friday morning, I rushed to read the pre-released first chapter of “Go Set a Watchman” and quickly realized I’d made a mistake.

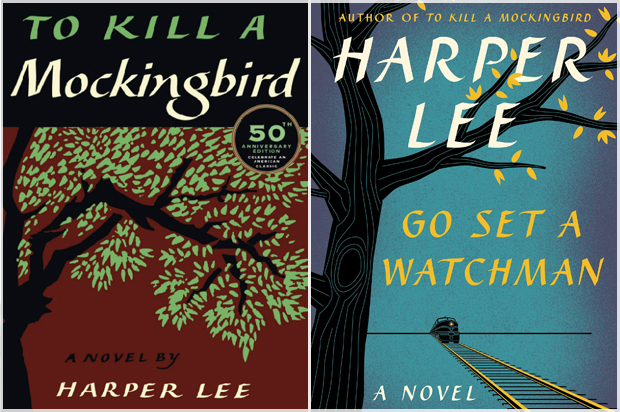

I’d been entranced by the controversy surrounding the manuscript — its sudden appearance after the death of Lee’s sister, her trusted protector, and rush to publication with Lee in diminished health. Over five long decades without a book from Lee after “To Kill a Mockingbird,” I’ve been suspicious and protective of her. So I sat down to read the first chapter with a keen eye. Was this really Lee’s work? If it felt authentic, would Lee live up to the brilliance of her first novel? Had she stopped writing because “To Kill a Mockingbird” was heavily edited by her buddy Truman Capote, as the old rumor has gone, and, without him, feared failure? Would the book be any good?

My mistake was that I’d forgotten to brace myself to reenter Lee’s world, emotionally. I’d forgotten that I was going to visit a kind of literary home – or, more pointedly, a literary father I’ve loved and admired for as long as I can remember.

When I saw the name Atticus Finch in print, I leaned back from my computer screen, my eyes welled up, and I started to cry.

Atticus Finch isn’t just a character for me. He isn’t simply Gregory Peck either. He’s a father, a good father, a rarity in literature. I saw much of my own father in Atticus, both lawyers, lean and tall with dark hair, who believed deeply in Civil Rights. I was sure that reading about Atticus who, like my own father now, was in his seventies was going to force me to confront my own father’s mortality, the loss of incredible goodness in my life.

But then the reviews started coming in. This Atticus Finch wasn’t going to live up to the literary father figure I’d come to revere. This Atticus Finch was a racist.

As a novelist, an intellectual instinct should have kicked in. I should be able to turn off my emotional response to a fictional character. After all, it’s my job to create them, draft upon draft.

It’s notable – in a very bizarre coincidence – that my new novel, “Harriet Wolf’s Seventh Book of Wonders,” centers around the life of a famous reclusive novelist, who hit her zenith mid-20th-century and whose final book – one that would have finish off a bestselling, beloved series – was long rumored to exist but was never published. I’ve been long-fascinated by writers like Harper Lee, J.D. Salinger and Emily Dickinson, who rejected public life. Looking at the world through the eyes of Harriet Wolf, my own invented reclusive novelist, was in some ways an act of wish-fulfillment—I’ve been jealous of their ability to hole up and turn away from the outside world. In fact, the act of writing — and, in particular, the act of writing this book, which I wrote, off and on, over the course of 19 years — allowed me a chance to temporarily insulate myself from the outside world.

But I didn’t first read “To Kill a Mockingbird” as a novelist with all of my literary anxiety. I read it as a little girl growing up a few blocks from my racist Southern grandparents in the midst of desegregation. Atticus Finch was a fictional character but his existence changed me forever. I believe that his existence manifested goodness in the world; and this belief in what literature can accomplish sustains me as one who writes and one who continues to go public with my work.

Out of an essential protective instinct, I choose to hold onto the Atticus I know for that girl I once was, and, as this year’s headlines were dominated by black men murdered in police custody, I still need Atticus Finch to be Atticus Finch.

Protectiveness prevails in the pages of “To Kill a Mockingbird” — Boo Radley’s protectiveness of Scout and Jem, Atticus’ protectiveness of Tom Robinson, and, I can’t ignore it, my enduring protectiveness of Harper Lee who, when in good health, let “To Kill a Mockingbird” stand as her complete gift to all of us. What I learned from “To Kill a Mockingbird” is this sense that our human dignity is tied to the human dignity of all of those around us. Since Lee – as reports indicate – didn’t edit “Go Set a Watchman” much at all, we are reading a novel that is haunted, but with no recognition of its ghosts. And perhaps it’s childish of me, but I’m going choose what haunts me, choose my own ghosts.