Since the end of World War II, the United States has fought five major ground wars—one in Korea, one in Vietnam, two in Iraq, and one in Afghanistan. By many measures, we’ve lost four of them (the first Gulf War is the one clear exception). The U.S. may be the world’s dominant military power, but we seem to have lost the ability to win.

Dominic Tierney’s new book, “The Right Way to Lose a War,” begins with a depressing premise: the United States will probably lose again. “We live in an age of unwinnable wars, where decisive triumph has proved to be a pipe dream,” he writes. For Tierney, a professor at Swarthmore College and a contributing editor at The Atlantic, the solution is not just to prepare to win wars. It’s to develop clearer plans for how to cut our losses and run when the situation demands it, instead of becoming bogged down in a protracted, fruitless conflict.

In our era of ambiguous, stateless wars, Tierney argues, “losing the right way is a victory.” He argues that the military needs to be ready to surge (adding more troops, briefly), talk (spin the narrative) and then leave (before it’s too late). The strategy, Tierney suggests, is less about pride, and more about pragmatism—and saving lives.

Over the phone, Tierney spoke with Salon about ISIS, nation-building and why the military destroyed all its counterinsurgency notes after the Vietnam War.

You’re talking about losing wars. I’m an American. Why does this make me feel so uncomfortable?

American culture is very much a victory culture, a culture of competition and winning. The notion of cutting losses or dealing with an unwinnable situation might seem vaguely unsettling and un-American. But the reality is that four out of five wars that the U.S. has fought in recent decades have become unwinnable. Although it might make us uncomfortable, I think it’s necessary for us to think seriously about the question.

In contemporary warfare, what does it even mean to win or lose? How do we define victory? How do we define loss?

Victory and success are about achieving your goals with a reasonable cost-benefit analysis. That holds true for all different kinds of wars. And if you look at American history before 1945, typically the U.S. was successful. But since World War II, only the Gulf War really passes the test as a relatively clear success. The other cases—Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan—are really stalemates, draws—perhaps failures.

In modern warfare, though, there’s a lot of room for spin, because it’s not like anyone formally surrenders. After Iraq, for example, politicians could say that Americans would appreciate the benefits of this conflict decades from now.

Yes, I think it’s true that the cost-benefit analysis of the war could alter over time. That said, I think it’s pretty unlikely that Americans are going to look at, say, the Iraq War anytime in the future as having been a great victory for the United States. Most likely, the dominant view would be that it was a very costly misadventure.

The opposite happens, too: conflicts that at first seem like victories can end up looking like defeats. The Spanish-American War, for example, looked like a clear American win. But if you went to the Philippines a few years later and talked to American soldiers facing the insurgency there, they might not have such a rosy view of the war’s outcome.

Sure, the U.S. pretty much bested the Spaniards. But even then there was something of a darker side, in a sense in that the U.S. participation in the Philippines triggered a counterinsurgency war. The U.S. managed to suppress the insurgents, but at a high cost. This was at the start of the twentieth century. In certain ways the Philippine war has been a harbinger of the difficult counterinsurgency campaigns we’ve come to know.

Do you think that American leaders consider victory in clear cost-benefit terms? Or are they imagining victory in another, less calculated way?

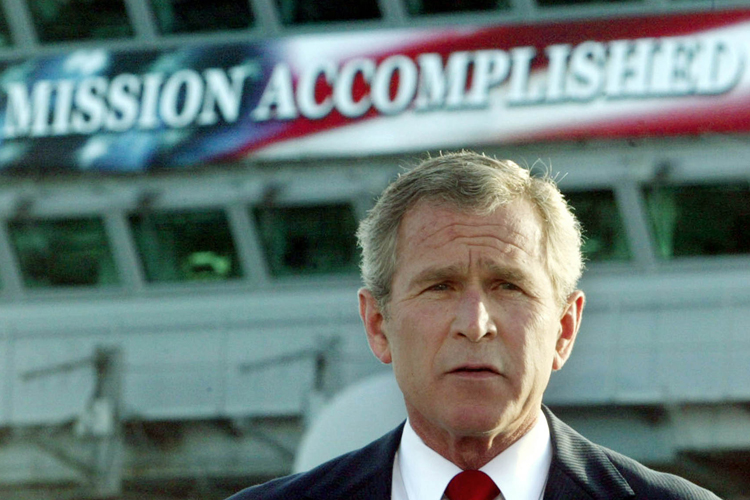

Well, the general pattern is that presidents of the U.S. tend to go through a very short-term mentality. Take the Iraq War: The focus was very much on overthrowing Saddam Hussein, and that was seen as the key element of success. But that was really a very narrow view of what success or victory meant. Real success, real victory means creating a state or enduring regime in Iraq. There was much less focus on that in terms of the planning.

You write that “before any military operations begin, leaders should analyze likely scenarios for concluding the campaign and achieving their goals.” Do leaders really not do that? I just can’t imagine sitting around, being about to invade a country—

[laughs] It does seem staggering, but this isn’t just a problem in the United States. When the Japanese deliberated attacking the United States at Pearl Harbor, the stakes were incredible. I mean, Japan was one tenth as powerful as the United States. But when you look at Japanese thinking in 1941, they focused very much on the tactical challenges of attacking the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor. But they had absolutely no plan for achieving enduring success against the United States.

The U.S. exhibited a similar kind of mentality in 2003 in Iraq, where they had a huge, very detailed analysis of the initial stages of the campaign, but not enough thinking about the bigger strategic picture—about creating an enduring regime. It is staggering that countries can do that, especially when the stakes are so high. But that is, in fact, the path of modern war.

Why are our leaders so short-sighted? Are they stuck in these old ways of thinking about war as a World War II-style conflict between sovereign states?

I think there’s a couple of things going on. The U.S. often goes to war very overconfident about how the war will turn out. There’s a sense that it’ll be a cakewalk—that the Iraqis will throw flowers at us, that Afghanistan will be straightforward, and so on.

Another piece is that Washington, the U.S. military, and Americans more generally do not like the idea of nation-building. It’s not a comfortable activity for Americans to be involved with. You don’t plan for it because you don’t really want to be doing it.

That reluctance makes sense. It’s hard for outsiders to come in and rebuild a country that isn’t theirs. Are there examples of nation-building campaigns, even with willing partners, that have actually worked?

There’s no question that fighting an entrenched insurgency is a very difficult thing to do. But not all nation-building missions fail. A good example of a successful operation is the nation-building in the Balkans, in the 1990s in Bosnia. Now, these weren’t perfect missions, but the civil war ended, and the presence of peacekeepers really helped. Peacekeeping can be very successful if the combatants in the civil war consent to the arrival of the peacekeepers.

Nation-building has many different types, from counterinsurgency to a more peaceful operation like the one in Bosnia. Some of these missions are quite successful.

Why has nation-building been so difficult for the United States, then? Do our leaders lack the knowledge to do it well, or the ability to apply that knowledge? Is there a problem with the military’s institutional culture?

I think it’s a combination of all those things. The U.S. military traditionally loathes nation-building, and it sees its primary mission as fighting and winning the nation’s wars, by which I mean conventional, inter-state war. The comfort zone of the U.S. military is a Gulf War, World War II-style operation. The reality is that the U.S. military spent many years doing different kinds of nation-building and insurgency missions, but it’s never embraced those missions. It’s always been [seen as] a kind of deviation from its true mission.

What we tend to see after these missions is a kind of backlash, like after Vietnam, where the U.S. military actually destroyed its own notes on counterinsurgency—the idea being that if we can’t do it, we won’t actually do it.

Meanwhile, political leaders are not very enthusiastic about nation-building. People on the left often see it as imperialism; people on the right see it as big government social engineering. It’s not a very popular endeavor. The end result is that the U.S. is a reluctant nation-builder and tends to want to end these missions as quickly as possible.

Why do we task the military with nation-building? It seems strange to expect a single institution to attack countries and to rebuild them.

Well, the U.S. military certainly wouldn’t be the only [institution] involved in nation-building. They have a range of other government agencies, like USAID and the State Department. But the military will always play a critical role in these nation-building operations because it has the capabilities. Especially in the immediate aftermath of regime change, there’s nobody else who provides security. Without security, really all of the other pieces of the nation-building jigsaw are not going to fit in its place.

So there’s no alternative to the military playing a key role, and therefore the military needs to train and prepare for these kinds of situations. It may be resistant to doing it, but you look around the world, and 90% of the wars today are civil wars. The kind of campaigns that the military and perhaps the American public wants to fight are very rare, and the kind of campaign that the military doesn’t want to fight is extremely common. Let’s be ready for these kinds of operations, because they’re almost inevitable.

You’ve written a smart book, and clearly there are lots of smart people in the military. But I keep wondering if there’s something about warfare that makes smart people do dumb things. No matter how much smartness we have, is that actually sufficient to bring about change?

There are plenty of smart people in the military, and yet when we look at these recent wars—Paul Bremer disbanding the Iraqi military in 2003, or the De-Baathification campaign—these were just genuine mistakes that were made in a tough situation. But then of course you have to cut slack to the leaders who were operating in a time of great uncertainty. It’s very easy for us to kind of Monday morning quarterback these campaigns years later.

On the other hand, before we went into Iraq, smart analysts raised questions and doubts about strategies and they were just ignored. So when you see these questions and these issues being raised, and see that the administration has just sidelined critics, I think it’s fair to be critical of that.

At the moment, when a war goes wrong, and the wheels start coming off, there’s basically nothing. There’s no guidance for a president; they basically just improvise their way out and that has not worked. So the idea behind the book is that there’ll be some kind of guidance, some kind of framework to understand this based on past experience, so that the president has to break the in-case-of-emergency glass, and there will be something there.

Something that has struck me about a lot of coverage of conflicts, including your book, is how few of the interviewees are from Iraq or Afghanistan or Vietnam. Is it possible get a complete picture without hearing their views of the conflicts?

There are large parts of the [Iraq War, for example,] that would be impossible to understand without doing a lot of interviews in Iraq. You wouldn’t quite understand the dynamics of the Sunni-Shiite divide, and of course you couldn’t simply rely on U.S. analysis. Many of the books that I read cover these topics and are woven into the analysis.

Probably the most useful [interviews for this book] are the primary American [military leaders], in terms of understanding the dilemma from their perspective; after all, that is the perspective that the book looks at. But I deliberately tried to broaden my analysis a bit: I traveled to Israel and talked to the Palestinian leadership and the Israeli leadership about the Gaza exit [in 2005], deliberately to take a case that was outside the of the U.S. experience.

Shifting to contemporary, or ongoing conflicts, if you were invited to the White House to talk to Obama about ISIS, what issues would you focus on?

This is a horrendously difficult challenge, no question. ISIS is far weaker than the coalition arrayed against it, but ISIS is united and ideologically committed, and the coalition arrayed against it is deeply divided, so it has a huge advantage in that way. What I would say to the administration is that this trend of limited use of force is probably the best option right now. In other words, it’s better that we use some airpower and training and special forces and so on, than staying out completely.

I’m not supportive of sending in ground troops. I think that’s exactly what ISIS wants to see, and I think that that would be very dangerous. But what we do need to do is think much more long-term. I would like to have a very serious analysis: What exactly is the endgame in terms of ISIS’s retreat and suppression? What does that actually look like? And after ISIS retreats, what comes next? What is the stabilization phase after ISIS? Otherwise, ISIS just might end up being replaced by a new type of threat.

Are you feeling optimistic about our level of planning right now? Not even specifically about ISIS; do you feel like we’re prepared to avoid sinking into another interminable fiasco?

I would like to see the U.S. military prepare for nation-building missions, but the truth is that doing so cuts against the grain of the U.S. military, and that doesn’t seem likely to happen. For instance, I mention in the book that the U.S. set up the Army Irregular Warfare Center to institutionalize the lessons from Iraq and Afghanistan. I would have argued that they should triple the funding of the center, but instead last year the Army decided to close it, even though irregular wars are the dominant kinds of wars around the world.

I’m not confident that the U.S. military is going to institutionalize lessons of Iraq and Afghanistan and keep the skillset, to the extent that it needs to. Obama has in some significant ways improved American foreign policy relative to the Bush administration. We’ve dialed down the crusading missionary sentiment. I think Obama’s sort of don’t-do-dumb-stuff mantra has a great deal of merit. But, on the other hand, we’ve also seen some difficulties. For example, in Libya in 2011, we overthrew Muammar Qaddafi and then basically just walked away, and now the Libya has collapsed into anarchy. We do seem to be repeating some of the same problematic behaviors.

It’s interesting that we still call it unconventional or irregular warfare, when it’s pretty much all we’ve done for the past 65 years.

That’s a great point. The fact that we call it “irregular,” or “unconventional,” says more about our view of what we want to do than it says about the actual nature of global conflict.