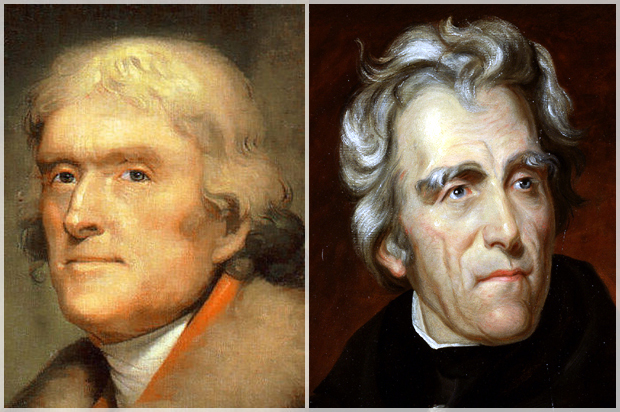

The Democratic Party of Connecticut has announced that its annual fundraiser, the “Jefferson Jackson Bailey Dinner,” will be renamed, keeping only the “Bailey” in its reconstitution. John Bailey, a Connecticut New Dealer and JFK supporter, never owned slaves and never fought Indians. The other two — Democratic presidents — were imperfect in the extreme and, presumably, no longer worthy of being honored.

Like removal of the obnoxious Confederate flag, symbolic acts in favor of historical fairness and social justice can do much good. But they obviously do not provide full answers. American slavery, a longstanding evil in a nation ostensibly dedicated to enlightened concepts of individual freedom and human rights, was succeeded by cruel decades of Jim Crow injustice. We are rightly embarrassed by blackface “comedy” and other such holdovers of past insensitivity. We nod agreeably as each generation of American liberals congratulates itself on overcoming one or another prejudice that beset an ancestor. As the job of erasing hatreds based on superficial differences carries forward, the well-intentioned sometimes bring up Band-Aid solutions to set the moral calculus aright. The Jefferson-Jackson Dinner does not rise to the level of racist iconography that the Confederate flag does.

That does not mean the Connecticut Democrats are misguided. Prodded by the NAACP, they are clearly reflecting on the recent Charleston shootings. And no one should forget such a tragedy. But why Jefferson-Jackson Day? And is the message they’re trying to convey at all meaningful?

First, let us explain, as far as the record is recoverable, the history of Jefferson-Jackson Day. In the first half of the nineteenth century, Jefferson’s birthday (April 13) was celebrated with public dinners and grandiose toasts to the Union — though the birthday boy himself humbly remarked that the only anniversary he cared to celebrate was the Fourth of July. At a Jefferson Day dinner in April 1830, in Washington, then-President Andrew Jackson famously took on the “nullifiers” of South Carolina, who failed to honor the cause of national unity. His toast: “Our Federal Union, it must be preserved.”

The first political gathering to be called a “Jackson Dinner” took place across several states in 1825, directly after the presidency was “stolen” by John Quincy Adams when, due to a four-way split of electoral votes, the second-place Adams was elected president in the House of Representatives. Democrats organized a fête for the general to ensure his victory in the next national election. Jackson’s primacy is also reflected in unofficial celebrations that took place every January 8, in honor of the hero general’s defeat of the British at the Battle of New Orleans on that date in 1815.

But Democratic Party dinners were not designated “Jefferson-Jackson.” Over time, the Democrat Jackson took priority over the Democrat Jefferson in party circles. William Jennings Bryan, who ran unsuccessfully for president, regretfully declined an invitation to speak at the Jackson Club of Omaha in 1895, at what was billed as a “Jackson Dinner.” The candidate remarked, however, that was encouraged to learn that the legacies of both Jefferson and Jackson were to be equally celebrated at the event.

Each generation of Democrats has manipulated the origins of their party to suit the spirit of the times. All, unfortunately, sidestep historical fact. Jefferson headed what was most often called the Republican (not Democratic) Party; its radical wing in the years immediately after its formation met as “Democratic-Republican” clubs. James Madison was the most visible and active member of Congress in the 1790s, when opposition to the Washington-Hamilton Federalists emerged as a recognizable political party; because Congressman Madison took the lead before obliging Jefferson to speak out, to be truly accurate these party gatherings should be called Madison-Jefferson dinners. Latecomer Jackson is the least democratic of symbols: he never sought an extension of suffrage rights in his home state of Tennessee or anywhere else. More verifiable Democrats of the early republican period are New Yorkers Aaron Burr and Martin Van Buren, both of whom restructured the party in their state so as to increase participation of ordinary people. The problem with our “greatness” measures — the academic equivalent of the current GOP candidates polling — is that a general lack of historical knowledge gives credit to some who don’t quite deserve it and denies credit to others who do.

The modern Jefferson-Jackson Day Dinner, that is, the Democratic fundraiser, dates to the era of Franklin Roosevelt when separately named Jefferson and Jackson Dinners were gradually merged. The principle behind these dinners — before the history of slavery and racial injustice preoccupied Democrats — centered on the cause of the “common man,” as traceable to the third and seventh presidents.

Here is FDR at the time of Jefferson’s birthday in 1932: “What is the real reason that Jefferson Day Dinners are being given throughout the length and breadth of the land, a century and a quarter after Thomas Jefferson was at the height of his career?” Other than the practical goal of electing Democrats, it was “to give renewed allegiance to the foundational principles of which Jefferson was the chief builder.” Roosevelt again, this time defending the New Deal in 1940: “Thomas Jefferson is a hero to me despite the fact that the theories of the French Revolutionists at times overexcited his practical judgment. He is a hero because, in his many-sided genius, he too did the big job that then had to be done — to establish the new republic as a real democracy based on universal suffrage…. Jefferson realized that if the people were free to get and discourse all the facts, their composite judgment would be better than the judgment of a self-perpetuating few.”

By mid-century, the official dinner was known as the “Jefferson Jackson Dinner.” President Harry Truman spoke at an event of that name that convened on Feb. 19, 1948, to mark the 100th anniversary of the Democratic National Committee; he called Jefferson “the father of American liberalism,” and Jackson “the man who later gave American liberalism even greater meaning.” He repeated, with conviction: “the party of progressive liberalism… carries on the traditions of Jefferson and Jackson.”

Truman integrated the armed forces and committed the Democratic Party to civil rights. Like the crusading Eleanor Roosevelt, he saw an opportunity to accord black America respect so long denied. But this moment, too, was the heyday of Jefferson- and Jackson-loving among liberals, so Truman imagined both as universal Democrats: “The supporters of Jefferson organized a political party of progressive liberalism that has continued in American political life down to the present day as the Democratic Party.” As for Jackson: “The votes of vigorous common men of eastern factories and western farms brought Andrew Jackson to the presidency in 1829. During the next eight years, that illustrious son of the frontier carried out a second social and economic revolution in America. Jeffersonian liberalism thus gave birth to and was carried on by Jacksonian democracy.” Reflecting on the 1830s, Truman observed further: “I am struck by how little our national problems change. Most of the issues tackled by Jackson were merely new phases of issues that had earlier confronted Jefferson. And they were substantially the same problems that confronted the nation a hundred years later, when one of the greatest Americans of all time came to the presidency — Franklin D. Roosevelt.”

Roosevelt-Truman Democrats, from the 1920s forward, defined the core problem facing American democracy in terms that mirror how we prioritize the problems of our day: “the undue influence of concentrated wealth.” The difference between the New Dealers and us is that for them, race did not rise to the level of concern that economic disparities did. In 1948, despite the activism of a minority led by Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, the Party believed in gradualism when it came to rectifying race injustice; admittedly, too, Democratic leaders sought to salvage the North-South alliance in the face of Strom Thurmond’s racist Dixiecrat rebellion. We, on the other hand, are constantly barraged by reports (often videotaped and impossible to ignore) of police violence, racist taunts and the counter-narrative tossed back in the conservative media that features critiques of knee-jerk political correctness.

Under current conditions, a Democratic stronghold like Connecticut is trying to make an important statement. But here’s the problem: Yes, Jefferson owned slaves. He was born into a slave society and was, even at his very best moment, a timid abolitionist. He rationalized that he did as much as any man to care for his human property, and he hoped that the next generation could do what his generation had failed to do. But he opted for expulsion of freed slaves beyond Virginia. Abraham Lincoln thought colonization to Liberia or the Caribbean was a valid solution to the race problem in 1860. George Washington did nothing as president (or at any other time) to improve the lives of black people and owned as a slave at Mount Vernon his wife Martha’s half-sister. He famously freed his slaves in his will, but only to occur after his widow Martha’s death, and presumably also because he had no sons to whom he might otherwise bequeath his property. Should we remove Washington’s name from the District of Columbia? Columbus, an ardent Christian, enslaved those he encountered in the New World. So, then, District of…?? No one looks good under this microscope.

Andrew Jackson is a somewhat different case, and both Roosevelt and Truman gave him a pass based on the imperfect published histories to which they had access. As much as Jefferson has been improperly idealized by Democrats as a proto-New Dealer, Jackson should be seen for the mediocre thinker and human rights violator that he was. Beyond the disgraceful treatment of Indians, whose sovereignty, to him, was a joke, and his unapologetic lifelong slave-owning, he was not even what we could call a democrat. The party he spawned was a Southern-dominated party that worked to disenfranchise free blacks and perpetuate the worst of racial stereotypes while promoting with the pseudo-science of Anglo-Saxon superiority.

Connecticut isn’t accomplishing anything of historical import by removing the names of two slave-owning presidents. It goes without saying that the imperfections of American party operatives are pretty universal — how many politicians’ private lives ever match their vaunted ideals anyway? If the Nutmeg State wants to comprehensively celebrate the progressive history of the Democratic Party, and it wants to acknowledge less degraded historical actors, then rename the fundraiser the “Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt and Harry Truman and John Bailey Dinner.” Maybe designate the menu so as to honor Connecticut’s literary icons, too: name the appetizer after Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” momentously revealed the inhumanity of slavery; name dessert after the democratically inclined political satirist Mark Twain — though he enlisted in the Confederate Army (okay, just for two weeks) and in all likelihood voted Republican after the Civil War. Hey, no one’s perfect.