When my father died in June of 2013, I wrote in my journal about how frustrated I was that at the moment I needed language to work for me, it deserted me. Words, language, the connective tissue between me and the world, had broken down, just as my father’s body was breaking down.

Unable to write, I once again turned to reading. In 2006, the first time I had experienced a significant loss, the grief literature had comprised the memoirs by Joan Didion and C.S. Lewis. Joseph Luzzi cites Didion in his new memoir, “In a Dark Wood: What Dante Taught Me About Grief, Healing, and the Mysteries of Love” (HarperWave, 2015). “I had left the house at eight thirty; by noon, I was a widower and a father,” he writes. While Luzzi was teaching a morning class at Bard College, his wife, Katherine, heavily pregnant with the couple’s first child, pulled out into traffic and caused a terrible accident. Shortly after an emergency C-section brought daughter Isabel into the world, Katherine died during brain surgery.

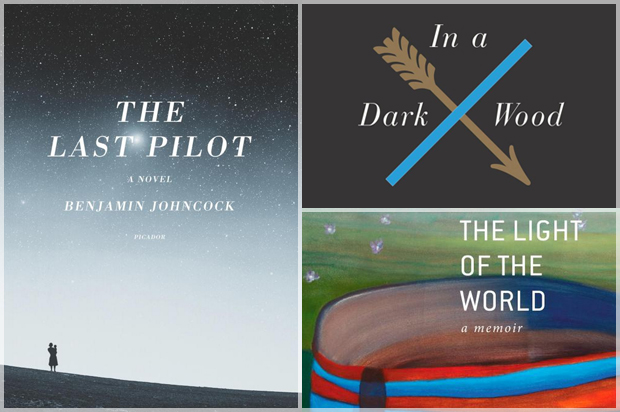

Luzzi joins three other writers whose new books encompass death and grief. Three are memoirs about the loss of someone close, while the fourth, Benjamin Johncock’s “The Last Pilot” (Picador, 2015), is a novel in which loss is ignored by its main character, which causes even more loss. The publication of these four books in a period of several months confirms the jarring declaration I heard at a recent writers’ conference that “death is a hot topic right now.”

I pursued a Ph.D. in Renaissance history at an Ivy League school, so I expected a book written by a Bard professor to jibe with my own more literary search for peace. As much as I wanted to love Luzzi’s book, and as much as I identified with his being a first-generation immigrant working-class child who had pursued the life of the mind as a way out, I struggled to keep reading. Luzzi’s need to hash out political conflicts and settle academic scores in the midst of writing about his wife created the uncomfortable situation of my wanting to argue with a grieving man—something I would never do in life.

I found a solution by skipping over the parts where he praised his wife by criticizing others. The book soared when Luzzi used Dante’s words to explain how grief made him feel; the times when Luzzi wanted me to draw parallels between the petty bureaucrats who drove Dante from his beloved Firenze and nameless academics who would have mocked his wife’s goodness were the book’s low points. (And his discussion of the role of fathers deserves its own essay, rather than whatever shorthand I would be forced to use here should I try to encapsulate it.)

Luzzi adopts Dante as his spirit guide to take him across the stages of grief, which he reorganizes to mirror the three parts of “The Divine Comedy.” For Helen Macdonald, her wish to make Mabel the hawk her spirit guide for negotiating her period of mourning in “H Is for Hawk” creates a marvelous, multilayered understanding of our relationship with nature. While grief is the subtext, this is a book about a woman’s rediscovery of a childhood passion: raptors and falconry. Like those little kids who have an encyclopedic knowledge of dinosaurs or types of truck, when she was a girl, Macdonald knew her raptors. The book that disturbed her as an 8-year-old, T.H. White’s “The Goshawk,” becomes her “what not to do” training manual. Early on she writes,

“…White wrote one of the saddest sentences I have ever read: ‘Falling in love is a desolating experience, but not when it is with a countryside.’ He could not imagine a human love returned. He had to displace his desires onto the landscape, that great, blank green field that cannot love you back, but cannot hurt you either.”

One may be tempted to think that Macdonald has simply substituted a hawk for the countryside, but avoid the temptation. This is one of those books bound to be a classic of nature writing, offering examples of sentences so shimmering I found myself halting in order to copy them down into my journal. She flew like a promise finally kept.

It takes a confident writer to cover material that Tom Wolfe defined as his own in “The Right Stuff.” Benjamin Johncock proves that he has the chops to put his own spin on the matter in “The Last Pilot” (Picador, 2015). A book about the first astronauts must encompass death, and as I read, I wanted to know how a fiction writer would explore grief. Loosened from the constraints of truthfulness, where would a novelist choose to go with language?

Johncock writes spare sentences, each diamond-like, free of any cloudiness caused by extra words. The prose is beautiful. But when it came to grief, I found myself wanting more. Show me what grief feels like, I thought, so that I may feel it, too. Isn’t the point of literary fiction to make that kind of empathetic connection with the characters?

Johncock gives us an emotionally stunted character incapable of giving voice to grief. I felt resentful, sure that I was watching a writer avoid the discomfort of writing the ineffable. Grief strips us of language, yes, but shouldn’t the writer even try? And yet, the pilot’s reticence to acknowledge his great loss complicates his mission, as that unspoken grief becomes an agent of destruction. And it was this plot development — Johncock’s acknowledgment of the cost of silence — that redeemed the novel.

My friends know how much I envy poets. Their facility with language makes me feel clumsy and clunky as I seek to translate experiences into prose. It’s not a surprise that the work that I found most effective in giving us a language of grief was written by the poet Elizabeth Alexander in “The Light of the World” (Grand Central Publishing, 2015).

One day, while a 50-year-old man was running on his treadmill, a heart attack killed him before his body hit the floor. Ficre, Elizabeth Alexander’s husband of 15 years, talks to his wife a few hours before he dies, when he insists that she should go to a poetry reading on campus where she teaches while he takes their two sons to the orthodontist. When she approaches the house that evening, it’s at the same moment that her son Simon has discovered his dad slumped in the basement. As she relates the lengths that she, and then a passing R.N., and then the paramedics and finally the E.R. doctors go to in trying to revive Ficre, the language builds up both the tension and the fear. When she first walks into the room where her husband’s body lies, my breath caught on a sob as I read:

“The penis, which is mine alone, lies sleeping on his thigh, nestled in its hair, the heart outside his body, and that is what I remember of his body, after the emergency room doctor met my eyes and made his pronouncement.”

In choosing to write in the expansive language of intimacy, Alexander opens up her language wide enough to pull the reader in after her. Over the next several hours, the only time I moved out of Alexander’s orbit were the times I needed to attend to bodily needs. The rest of the time, I let myself feel what Alexander was generous enough to share.

Perhaps Alexander’s experiences of grief felt the most real to me because they also validated the things I had felt. The book is not narrated in anything approaching chronological order, but only the easily confused will complain about that. The book manages, in its non-linear structure, to replicate the structure of grief. Most people know about the five stages of grief. But I don’t think you understand how those stages work until you’ve gone through a period of mourning. No one warned me that I might feel all five stages in one 15-minute period, or that I might think that I had finally moved beyond one stage only to find myself practically starting over again when some memory in the shape of a song on the radio hurtled me back to another time. About how I would repeat certain stories over and over again to anyone who would listen in hopes that this time, when I told the story, it would make sense when it had not the dozens of times before. Or how I might long for company and resent its presence in the space of a heartbeat. In its structure comprising repetition, memories sparked by a recipe or song, or the frustration at conflicting needs, Alexander narrates that which resists the logic of narration.

Some critics declare that we have reached the end of memoir. I hope not, because memoir serves a purpose. While writing about her grief might have helped Alexander to name it, for me, I read about her grief in order to understand my own.

The language of grief is not a specialized vocabulary of secret words. It is ordinary language heated and hammered into receptacles that hold themselves steady long enough to fill with a writer’s meanings. For some writers, the language of grief is only accessible by adapting words written by others. After all, Dante suffered great loss and his suffering gave us a work for the ages. The language of grief may also be accessed in the substitute of one body for another, whether that be the body of nature or the body of a hawk. The language of grief may also be silenced, but silence smothers. Alexander’s writing dances a Pasa Doble with grief, and she reminds us that grief belongs to those who loved.

C.S. Lewis wrote in “A Grief Observed”: “She died. She is dead. Is the word so difficult to learn?” Until I read Elizabeth Alexander, I thought that no one had transformed common language into something as powerful as the words of Lewis. But from this moment forward, for me, the language of grief will begin,

“I just lost my husband. Lost implies we are looking,

he might be found. I lost my husband. Where is he?”