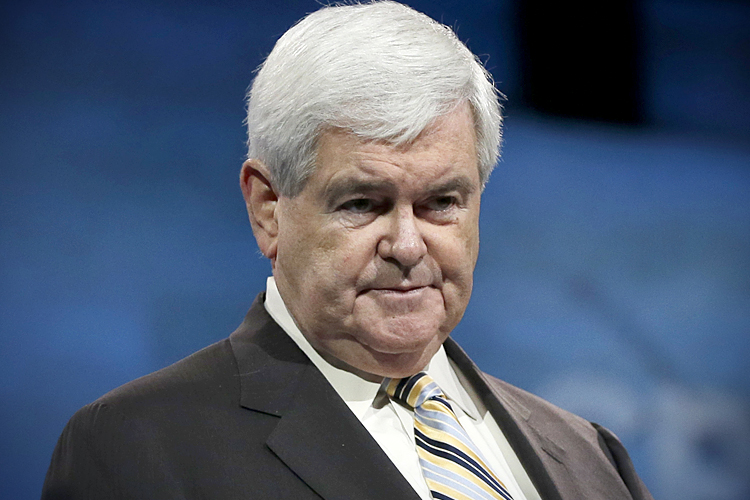

When the the Supreme Court first unveiled Citizens United — the landmark 2010 decision that gutted U.S. campaign finance law and handed the forces of plutocracy their greatest victory since Ronald Reagan was elected president — former Republican Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich was ecstatic.

“Citizens United was a great victory for free speech,” he declared in an Op-Ed for the ultraconservative Human Events, hailing the court’s ruling as one that that “strengthens” American democracy by “making it easier for middle-class candidates to compete against the wealthy and incumbents.” Critics of the ruling, according to Gingrich, were “near-hysterical” and “exactly wrong.” They were supporters of what he called a “bureaucratic” model of regulating campaign finance — which was, needless to say, “anti-freedom” and bad.

But what a difference five years can make! Speaking to Politico’s Glenn Thrush at some indeterminate point earlier this summer, Gingrich offered a much less sanguine assessment of Citizens United’s effects. “I think it’s very frightening,” he said of the increasingly mundane spectacle of watching presidential candidates grovel for the 1 percent’s affection. “I don’t think the Founding Fathers intended for the U.S. to be an oligarchy,” he added. The rise of a donor class of imperious billionaires was, Gingrich warned, a “dangerous” new trend — and one corrupting both sides of the aisle in Washington.

Anyone familiar with Gingrich’s ego (which is legendary) couldn’t help but wonder if the thrashing he suffered three years ago at the hands of pro-Romney super PACs accounted for his change of heart. Indeed, you can find examples of Gingrich complaining as early as 2012, during his failed run for president. But while Gingrich’s estimation of Citizens United may have changed, his preferred system of campaign finance has not. He still thinks Citizens United didn’t go far enough; and he still thinks corporate donations should be unlimited — just so long as they’re disclosed publicly, too.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is when the fundamentally bankrupt nature of Gingrich’s conservative populism is most apparent. Because that is the moment when it becomes clear that Gingrich is criticizing individual donors, not the whole plutocratic system. Gingrich didn’t have a problem with super PACs when casino magnate Sheldon Adelson was wasting an obscene amount of money on his vanity campaign. What really bothers him, it seems, is not the rules of the game. It’s the fact that the biggest winner thus far is Jeb Bush.

Assuming this is indeed his true motivation, it would not be the first time Gingrich has quarreled with the Bush dynasty. For example, when Gingrich was having his short-lived boomlet as the conservative base’s favored alternative to Romney, George H.W. Bush was one of the many Republican graybeards who seized the opportunity to air their grievances. “I’m not his biggest advocate,” the indefatigably WASP-y ex-president told the Houston Chronicle. He then recalled a moment during his presidency when Gingrich essentially stabbed him in the back, pretending to support a Bush administration-backed measure before lobbying against it.

At that juncture in his career, Gingrich was maniacally working to forge what would ultimately become 1994’s “Republican revolution.” And while conservatives tend to look back on the first President Bush fondly now, Gingrich’s task in the late-80s and early-90s often required him to depict Bush as exactly the kind of moderate squish Republicans could do without. When Bush famously — and admirably — reneged on his “no new taxes” pledge, Gingrich was apoplectic. (It was ostensibly Bush’s change of policy that Gingrich hated; but I’d be remiss if I didn’t note that the president decided not to consult Gingrich, who was the House GOP’s whip at the time, in advance.)

Finally, no recap of the dysfunctional relationship between Gingrich and the Bush clan can be complete without noting George W. Bush’s 2000 campaign theme of “compassionate conservatism.” Gingrich had already been forced to leave the House in disgrace by the time “W” was running for president. But because conventional wisdom held him responsible for the GOP’s terrible showing in the ‘98 midterms, the need to draw a contrast between him and the next presidential nominee became an article of faith among many Republicans. Thus was “compassionate conservatism,” which implicitly affirmed Gingrich’s public image as an unfeeling ideologue, brought into the world.

In the more than 15 years since the younger Bush’s first campaign for president, the war between the Bushes and Gingrich has cooled. But it was not over; and as Jeb’s campaign has once again made the family the center of the Republican world, Gingrich has once again fallen into the old habit of kicking dirt in their direction. Last summer, he blamed the public friendship between Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush for “resuscitating” the Clintons. “The consequence,” he warned, “may be a Hillary Clinton presidency.” And when Jeb’s candidacy had the chattering class talking in late-2014, Gingrich made a point of going against the grain and declared that Bush was not a front-runner.

Now that Bush has gamed the post-Citizens United system and raised more money than Croesus — and now that he remains the most likely nominee, despite the phenomenon that is Donald Trump — it’s hardly surprising to hear Gingrich voicing some new concerns. But don’t mistake this for a sign that conservative elites are ready to see the errors of Citizens United’s ways. They’re doing no such thing. These are merely the grumblings of a jealous megalomaniac who relentlessly conflates principle and self-interest. Put simply, it’s just Gingrich being Gingrich.