Iceberg Slim is an influential cult writer who many readers have never read. His vivid and relentless autobiography, “Pimp: The Story of My Life,” from 1967, tells of the quarter century the author (born Robert Lee Maupin; he later became Robert Beck) spent running women, both black and white, in several Midwestern cities and often with very little apparent empathy or outward emotion. He also published several novels, including “Trick Baby,” made into a 1972 blaxploitation movie. Slim died in 1992, as the Los Angeles riots raged near his home, at the age of 73.

Scottish writer Irvine Welsh has written that Slim “massively influenced popular culture through music and film. In terms of that influence he’s probably the most dominant writer since Shakespeare.”

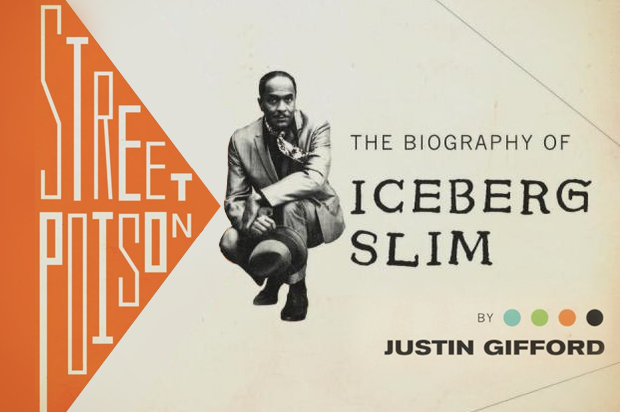

Justin Gifford’s “Street Poison: The Biography of Iceberg Slim,” has just been released. “Mr. Gifford’s taut biography is important and overdue,” Dwight Garner wrote in the New York Times, calling the biographer “a dogged researcher who arrives at a somewhat unexpected conclusion: The stories in ‘Pimp’ are mostly true.”

We spoke to Gifford, a professor at the University of Nevada at Reno, about the writer, the legacy and the life. The conversation has been edited slightly for clarity.

Let’s start with Iceberg Slim’s legacy and then double back to the life. Can you give us a sense of his impact in movies, music, fiction, and elsewhere?

It’s funny – you could probably say that Iceberg Slim is better known in the popular consciousness through his by-products than by his actual works. When it comes to him writing “Pimp,” that had a direct impact on blaxploitation films of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, partly because of his novel “Trick Baby” being made into a blaxploitation film. White screenwriters would often lift things directly out of his books, whether characters or the lingo he used or the streetwise style of his books. You could think about his books as the literary equivalent, and cornerstone of, the blaxploitating genre.

In terms of the stuff that comes after, he had a massive impact on hip hop in the early ‘80s. He’d put out a spoken word album in the late ‘70s, “Reflections.”

Hip hop was just starting to take off — this was the age of Grandmaster Flash and Run D.M.C. Ice-T was one of the newcomers on the scene — he took his name as an homage to Slim and created a lucrative career as a pioneering gangsta rapper. The same goes for Ice Cube: He also took his name from Iceberg Slim and was a big fan of the books. Jay Z, when he got his start, also referred to himself as Iceberg Slim, and Slim’s name comes up in a number of hip hop songs, by Notorious B.I.G., to Nas, to underground rappers.

And then there’s other kinds of black cultural phenomenon, like [African-American] comedy – Dave Chapelle, Katt Williams and others will routinely cite Iceberg Slim or “Pimp.” Chris Rock, at the wrap of every single one of his movies, will hand out a copy of “Pimp” to the cast and people working in the film, and tell them that all of the answers to life can be found in this book.

What’s drawn people like Ice Cube and Chris Rock to Slim and his work? What do they see in him?

That book “Pimp” in particular is an incredible resource for writers and entertainers and those working in the imaginative arts.

The style of those books is so brutal and unrelenting; the vernacular is so specialized that there’s a glossary at the back of “Pimp.” The book has a Shakespearean quality to its language and drama.

It’s also a book that never quite crossed over to the mainstream — it still remains an underground classic. That genre never crossed over to the mainstream like Motown or “race records” or other kinds of white-backed black cultural products. These [books] stayed in the mom-and-pop liquor stores and military bases and prisons where they were sold and read. For entertainers like Ice-T and Chris Rock, this represents a kind of uncompromised black anti-hero they can draw from to create their own stylized persona.

I expect you knew the outlines of the life story – Slim lays a lot of it out in “Pimp” – before you started the book. But were there things that surprised you as you got deeper into the life story?

That was my favorite part of the project: not calling Slim out, but testing some of the things he had projected in his autobiography and his other writing, to see if there was more to the story. What I found was that, first of all, most of everything found in his books is true.

What I did find, too, is that he omitted a lot of things from his life that he didn’t want to put in his books. And for me those ended up being some of the most powerful stories.

One instance, when I went to the Wisconsin Historical Society, looking at old records … The librarian came up to me and said that right next to the file for [his then name, Robert Maupins] was a file for Mattie Maupins … I’d never heard of Mattie Maupins, but when I looked at it I recognized immediately that the address was that of Iceberg Slim’s mother. Wait a minute — he knows her somehow … Mattie Maupins was, it turned out, Iceberg Slim’s first common-law wife, and he never told anybody about her. This is a part of his life he basically hid from people.

Stories like that really fill out the picture in a way that his own autobiography, “Pimp,” doesn’t quite tell us. There’s more to the story there, and that’s what my biography is trying to get at.

Slim was, famously, a pimp for something like 25 years. How did he treat the women who worked for him?

Oh, terribly. I mean, he was just absolutely ruthless. I tried very hard in my book not to sugarcoat stuff – not to glamorize of glorify this figure, but to hold him accountable.

It’s in his own words – he physically abused these women. It’s one of the first lessons he learned from the older pimps, that you needed to physically abuse them to keep them in line. He read Freud and Jung and other psychoanalytical books when he was in prison, to learn how to tighten up his psychological game.

Yeah, he was unrelenting about it. He felt a lot of guilt about what he was doing – he had these terrible nightmares about beating his own mother … He did a lot of cocaine and a lot of heroin.

You’re a professor of literature: How do Slim’s books stand up — aside from the life story and cultural context — as pieces of writing?

He is the top of this genre [of street lit]. There are people imitating Slim. But Slim brought something different to the game, that puts him in an entirely different class. If you ask how do these pulp novels fall into a class of literature, I’d put him right in there with people like Malcolm X and Claude Brown, of African-American writers working in an autobiographical tradition.

But I’d also put him in the same category as someone like Mark Twain, who’s using vernacular to tell a particular kind of American story. I think that’s what Slim is doing as well.