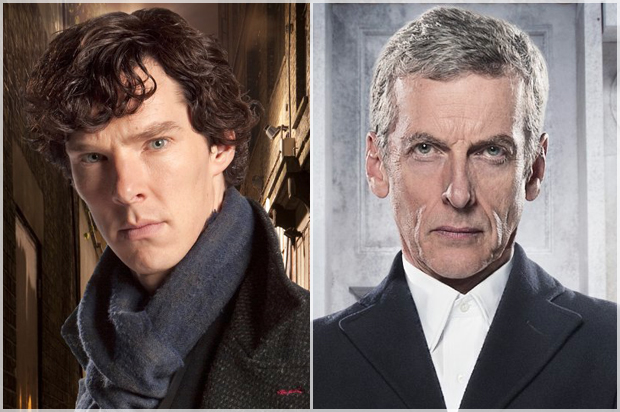

Steven Moffat is the most reviled television showrunner working today. As the creative force behind two beloved BBC shows — the long-running and iconic “Doctor Who” and the internationally beloved “Sherlock” — he’s created enormous fanbases that hold him directly responsible for their happiness, whether that’s casting Peter Capaldi as the 12th (and current) Doctor or writing in an atrocious caterpillar mustache for Martin Freeman’s John Watson. Other showrunners hear from their fans, yes. But due to the popularity of Moffat’s shows — and the fact that he himself comes as a fan to both humanoid Time Lords and 221B Baker Street — he is often called upon for a particularly personal reckoning with fans.

Sometimes the audience’s criticisms are superficial. Sometimes, the criticisms are about storytelling. And sometimes they’re damning in a bigger and more serious way. As Moffat’s shows have become more and more popular — fueled by Capaldi’s casting, the season-two cliffhanger of “Sherlock” and the increasing international fame of Martin Freeman and Benedict Cumberbatch — fans and critics alike have observed race-inflected insensitivity, mishandling of queer characters and most frequently, a laughable inability to write female characters. I see it, too; Moffat’s sensibilities can be a reflection of the worst sides of the British status quo, while deceptively cloaked in the intellectual optimism of fast-talking genre fiction. It doesn’t help that he is a fast talker, eager to give off-the-cuff remarks in the moment that aren’t quite as charming out of context.

And yet the “raging Lefty Scotsman,” as he referred to himself, turned out to be quite a thoughtful subject when it came time to discuss both “Sherlock,” hopefully returning this Christmas, and “Doctor Who,” whose ninth season premieres September 19. I mentioned casually to Moffat that the first show of his that I watched was 2000’s “Coupling,” a cynical take on hetero relationships that fictionalized Moffat’s own courtship and marriage to his wife and producer, Sue Vertue. Moffat winced when I told him. “Talk about gender essentialism,” he said wryly. With that setting the tone, I figured all bets were off. Below, Steven Moffat on why we don’t have a female Doctor, characters of color, cultivating female fans and how, exactly, to write a TV show.

Your shows, “Doctor Who” and “Sherlock,” inspire incredible fandom — and as you said in March, you write Sherlock Holmes fan-fiction for a living. What is it like to approach these pre-existing characters as a fan — being the number-one fan, if that makes sense?

[Laughs.] I never think of myself as the number-one fan! Oh, God. Fan One.

It’s been a long time now that I’ve been doing “Doctor Who.” I’ve been on the other side of the screen to the point where I now struggle to remember what it was like not to be involved in “Doctor Who.” [Laughs.] Even though I grew up with it! It’s probably a good exercise in how to make telly well: You should never think you own your series. Even if you invented it, you shouldn’t think you own it. Because you don’t. You sorta don’t. You make it, and you make money out of it — which is awfully nice — and it’s great fun, but you don’t own it, because creative enterprises aren’t owned.

They’re shared, maybe? Between the fans and the creators?

I used to very resistant to the idea that once the art is finished, it belongs to the audience — but then I realized, that’s exactly how I behave. That’s exactly what I do. [Laughs.] I watch an episode of “Doctor Who” or “Sherlock” God knows how many times before it goes on air, and then I will never watch it again. That’s it, over. I don’t have the same feeling. Up until that point, I’m usually sweating — full of hope or fear, or usually both, about whether it’s shit, or any good. And then it goes out, and whatever happens, praise or blame, it all just drifts away from you. It’s just a thing you did. And literally, unless someone makes me, I never watch it again. [Laughs.]

It’s certainly true that for whatever combination of reasons, there’s a special kind of fervor to your fans. Partly it’s because the way you write your shows, you have a really intoxicating combination of both what fans really want to see and a little bit of the emotional manipulation that hooks fans in.

To be honest, that’s just people. That’s an audience. I’m trying to manipulate an audience. [Laughs.] When people say, “The show was manipulative,” I think, What do you think the fucking alternative is? You understand that we just went into a big studio and pretended? This is entirely made up. He’s not really crying; she’s not really dead — [Laughing.] of course it’s manipulative! If it wasn’t, it’d be very boring. That funny thing that happened? It didn’t really happen. We made it up.

I do think that your shows are particularly good at getting that reaction from the fans.

This is how you write television — this is how you write anything: Someone is on their way out the door and “Doctor Who” comes up. They’ve got their jacket on. They’re going to the pub on a promise; there’s love and everything waiting for them. What are you going to do now? You’ve got three minutes until the title sequence, which they’ve seen before. So that’ll be tough. How do you get them to stop? And then one minute later, how are you going to hook them? To keep watching? And then, what are you going to do just before the title sequence that is so riveting that they say, I’ll just see how that resolves, and then I’ll go? And, by the time that resolves, they’re wondering about something else? You’re pulling them back to the sofa.

When people ask me — and it always comes out wrong, so quote me with care — you can’t write it for the fans, because they’re already watching it. You’re specifically writing for the people who have the lack of wisdom — that they have not decided to watch “Doctor Who” today, or “Sherlock.” I’m going to bring them back into the room — to sit next to the fan, who was going to watch it anyway.

I’m not saying that in a bad way about fans — I’m a fan myself! — but I’m in the business of recruitment. Because people are dying — people are dying, and that means the audience is going down, so how am I going to get new people in to watch this show. D’you know, they say the audience is stable, but it’s not. Because they’re dying, they’re wandering off to other shows, they’re going to another countries, they’re falling in love. We keep it stable by recruiting new people, particularly children. So we’re always saying, how are we going to get someone else to watch it?

That certainly explains the feeling I have, watching “Sherlock,” that the story I think I’m watching is shifting in front of me.

It’s also playing the game of, what kind of story are we going to tell. Is it going to be this kind? That kind? Could we go off this way? The longer you can keep them saying — Uh, is it going to be that? Oh no, it’s not! Oh, that’s just stopped! It’s a feeling of surprise that’s more than just twists. I’m probably slightly too prone to do twists, but they don’t really matter. What matters is that you’re in a constant state of — ooh! Oh! I didn’t, that’s interesting — engagement with the show, trying to work out what’s coming. You musn’t ever let people think, oh, I’ve got ages to go. You want to be surprising people, so that they don’t feel all they’re doing is watching people pretending on a screen. You’ve got to give them something that off-balances them, seduces them, amuses them, or just rewarding them. Here’s a lovely thing, here’s somebody really funny, here’s something you’ve always wanted to see. And you know what, you get to see it.

That’s interesting, because, as you know, you’ve been criticized for lack of representation of minorities and women. I can see how your emphasis on storytelling could make those issues not important to you, as you’re focusing on the plot twists.

What do you mean, “not important to me?”

I wonder if, because you’re so invested in what seems to be the moment-to-moment narrative — and, as you say, pulling people through — that you’re not so interested in stepping back and thinking to yourself, “well, how will I improve representation in this season?”

But I do! I do think about those things — this is something I take seriously. I know I’m being portrayed the other way, but I work very hard, and it’s not always easy. We need to do better on, certainly, the ethnic question. I thought when I first took it over — oh, what the hell, we’ll just audition people of all races for every part, and it will average out. I don’t know why an old Lefty like me had such faith in the free market; it did not work out. It does not work out. You’ve got actually decide that’s what you’re going to do. Lenny Henry has been very interesting on that subject. A few years ago I thought: Oh, quotas, what a ridiculous idea. Then I realized, quotas are a perfectly sensible idea! There’s nothing wrong with them! Now we’re actively trying to get that.

The female question — I wish I was allowed to list the female writers that have turned down “Doctor Who.” [Laughs.] In fairness to me, I’ve done quite more than anybody else.

Do you have a sense of why it’s difficult to hire female writers for the show?

I think it’s becoming easier. And again, quote me with care — people are very inclined to decontextualize things I say in order to make me sound venomous. I think it is that the old show, at least at the fandom level, was a boy’s show. Boys tended to watch it more than girls. If you went to a “Doctor Who” convention prior to 2005, it’s all blokes. You go now, it might even be more women than men — which I think is fabulous. It’s good for us blokes that girls are liking [science fiction]! Come on! At last!

And as you said, the audience isn’t stable, so you want to get as many viewers as you can.

Yes, exactly. Russell [T. Davies, “Doctor Who” executive producer and writer] was absolutely saying, at the very beginning of this, “We’ve got to get girls watching this show!” When “Doctor Who” announced it was coming back, all the men in Britain jumped up and down and all the women are going, I don’t give a fuck. We engineered that change.

So, you get the job of “Doctor Who” showrunner, and 4,000 men jump at you, saying please please please, I’ve waited all my life to write “Doctor Who,” practically no women. It’s different now. Catherine Tregenna, I had to persuade to write “Doctor Who” — I pitched to her. Sarah [Dollard], she has genuine passion and genuine excitement to write. And that’s the first time I’ve had a woman on the set asking [breathlessly], “Can I see the TARDIS?”

It’s only just happening now because it’s only been a completely seductive show for women since 2005. You have to be an experienced writer—I’m not taking any old damn writer, I’m taking people at showrunner or thereabouts.

Fan culture and geek culture have been male-dominated for a long time.

Yes. I used to go to a “Doctor Who” fan event, first of every month, in a pub in London. All blokes. All blokes.

Before you were writing for it?

Oh yeah. Long before. And a while after, too, but then it got pressuring. [Laughs.] All men. Only a few women. I remember Jenny Colgan, who writes “Doctor Who” fiction, saying she had to pluck up courage outside, that she couldn’t go in, because it all seems to be men. Now, I swear if you went to a fan event like that — which I can’t really — there’s loads of women there. And that’s brilliant! I can’t see how that doesn’t make a happier group. You know there’s wee romances happening all over the place. There’s going to be loads of “Doctor Who” babies in the world.

Bearing all that in mind, why do you think the time wasn’t right for a female “Doctor Who”?

Because I wanted to cast Peter Capaldi. If there is any other player on the board other than the person who excited you the most in the role, “Doctor Who” would go off the air, so that’s what you have to do. Was the time right? I don’t know. I think it would have been a disaster if we’d cast a female Doctor when David [Tennant] left. I believe. Disaster. Possible, this time. I think I should get a little more credit for being the only person who’s made it possible. [Laughs.] It wasn’t part of the fiction of the show until I wrote it. And I keep establishing it. But I think when that day comes — whatever showrunner that is — then the BBC will say, “Tell me how this is definitely going to work.” Because, I tell you, there are two venomous packs here. A lot of people in the middle, sensible enough to say, “If it’s good, I’ll like it; if it’s not good, I won’t like it.”

The outliers are more vocal.

And they’re both wrong! They’re both wrong. One saying, “It would never work.” What do you mean, it would never fucking work? How the hell would you know that? The other one, “It’s absolutely necessary it happens now.” No it’s not! It’s not necessary! It may never happen! Don’t be silly. There are no absolutes. Could you both join the one in the middle and please stop yelling at each other. And please stop yelling at me. [Laughs.] I’m very nice.