As the national conversation about criminal justice reform has progressed, a much wider variety of perspectives and voices has been introduced into the mainstream. In contrast to the situation in the “tough on crime” ’80s and ’90s, it’s no longer exclusively the victims — or hypothetical victims — of crime who have a say. Increasingly, it’s the people and communities who must bear the weight of a broken paradigm that are being heard, too.

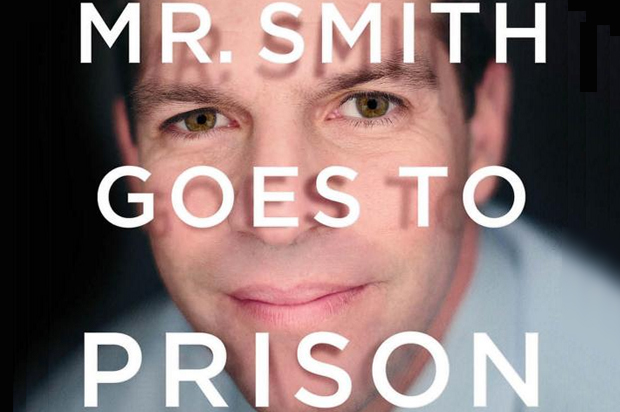

That said, the dialogue still has its limits. For obvious reasons, it’s especially rare to hear from someone who understands the criminal justice system from the viewpoint of both the outsider and the formerly incarcerated. And this is just one of the reasons why former Missouri state Sen. Jeff Smith’s new book, “Mr. Smith Goes to Prison: What My Year Behind Bars Taught Me About America’s Prison Crisis,” is so valuable. With empathy and insight, Smith’s book takes on one of the country’s most complicated and fraught policy issues while also providing a gripping memoir of an experience all of us would prefer to miss.

Recently, Salon spoke over the phone with Smith, now a professor at the New School, about his book, criminal justice reform, and what the national debate, which is largely conducted by those with no real experience with the penal system, tends to miss. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

Let’s start at the beginning. How did you come to find yourself in prison?

So I was running for Congress in 2004 and it was very much an uphill battle. I was running against [a scion of] a political dynasty named Russ Carnahan. We started about 50 points behind on the polls but we were able to come a long way. We were closing [in]. And then, a few weeks from Election Day, two of my aides approached me and told me that a man had asked to meet with them about potentially putting out a flier … and instead of telling them, “Don’t meet with him” or “Why don’t you look into this guy’s background,” I said, “Look, I don’t want to know what you guys do.”

Now, I knew something was wrong. I knew it smelled funny. I didn’t know the finer points of campaign finance law, but I knew enough to know this was fishy. But they went ahead and met with him, and my campaign broke the law by giving this third-party person information that was publicly available but that campaigns are not allowed to give to anyone else. The third party ended up putting out a flier and it didn’t really have any effect on the race (I lost by 1.6 percent) and then I signed an affidavit a couple of weeks later … which said I didn’t know anything [about the flier], which wasn’t true, since I knew that my aides had met with a guy who I thought probably put [it] out.

Nothing happened immediately thereafter, though, right?

Five years later, after I’d been elected to the state Senate, my best friend called me and told me that the man whom my aides had met with had been picked up by the feds for spousal abuse, cocaine possession, illegal weapon possession, drug distribution, wire fraud, bank fraud, mortgage fraud; and was now the chief suspect in the car bombing of his ex-wife’s divorce lawyer. I could not believe that I had let my staff meet with this monster. And for the next six weeks or so, my best friend and I went back and forth about what we would do if the feds came to us, and I told him that I was already out there with an affidavit and I was going to stick to my story.

And little did I know that that entire time, my best friend was wearing a wire. And that’s how I ended up in prison.

How did the experience differ from your expectations?

I didn’t go in with a lot of expectations, to be honest. I knew a lot of people who’d been locked up; my district was full of people who’d been locked up. So that probably helped me a little bit in terms of preparing for the experience.

But I was endlessly surprised by the amazing ingenuity of the guys I met in prison, whether it was learning how to concoct a meal out of scraps of food stolen from a warehouse that tasted like a gourmet meal — or at least did at the time [laughs] — or whether it was learning how to make weights out of sticks and stones tied together when the prison was on lock-down and no prisoners were allowed to go to the weight pile. There was just so much ingenuity, especially from a strictly entrepreneurial perspective.

What do you mean by that?

Like guys figuring out how to make money inside prison in order to purchase things at the commissary to make their lives a little bit easier. Most guys in there, they don’t have any money — a lot of them still owe the court money — and their families in many cases have abandoned them. No one is putting money on their books. And contrary to conventional wisdom, it’s not like, “Oh, you get treated fine; three hots and a cot; you’re taken care of.”

No. You’re given this tiny little one-inch bar of soap and a toothbrush that’s also about an inch long and told, “Hey, make do.” If you want to have just the basics to be a sane person, you need to earn money to buy these things at the commissary — items that are marked up 30 to 50 percent of what you pay on the street and are generally of pretty poor quality. So I was just continually amazed at how guys figured out ways to make money.

Is that part of what you’re talking about when you argue that our prisons and jails don’t rehabilitate people so much as teach them how to survive within the criminal justice system itself?

Instead of harnessing the incredible and mostly untapped entrepreneurial potential in our prisons, we try to crack down on it. It doesn’t work; prison economies still run. But instead of nurturing these skills people have in enterprise and nurturing it and saying, “This is how you could sell computers; this is how you could sell software,” etc., there’s precious few programs in this country to [encourage] that.

Yet almost everything we do on the inside makes it impossible for [incarcerated people] to have that chance. There’s almost no attention paid to rehabilitation. I write in the book about the courses that prisoners who are on their way out take. There was a course in computers, which meant that we went into a room with computers, they told us to turn it on, we sat there for 40 minutes, and then they told us to leave. Everyone who left the prison I was in goes out on the street not even knowing how to point and click.

How do you find a job in today’s day and age if you don’t even know how to use a computer? It doesn’t make any sense. And if you can’t find a job pretty quickly, you’re not going to have any money; and you have to pay for your halfway house, you have to pay for things almost as soon as you get out. So if you combine the lack of rehabilitation in prison, the tendency of employers to refuse to hire people that have convictions, and the difficulties in just getting housing and transportation and just the very basics (like having decent clothes for interviews) and you think about all the obstacles that are stacked against ex-offenders…

It’s really surprising that only two-out-of-three former offenders re-offend in this country.

Let me play devil’s advocate and echo an argument I’ve heard before and I’m sure we’ll hear again. Why should we devote resources to rehabilitating these people if they didn’t care enough about their lives to keep out of the criminal justice system? If they cared and sought to make something of themselves, they wouldn’t have ended up in prison in the first place.

Well, from the minute I got there, people were interested in speaking with me about politics; people were interested in speaking with me about policy; people were interested in speaking with me about education; people were interested in speaking with me about business plans they’d written up. Almost every day — and sometimes more than once in a day — guys would come up to me to talk about their future and flying straight.

They almost uniformly regretted what they’d done to get [in prison]; that doesn’t mean that they thought they had a lot of different options to make money in the neighborhoods they grew up in, but they wished that they hadn’t done it because most of them had [families]. This notion that guys get in there and they have no interest in ever being productive citizens, it’s just not right.

Since you’ve now had the perspective of a politician as well as someone in the criminal justice system, are there any ways that the ongoing discussion about reform within elite circles reflects an outsider’s ignorance or bias?

I think people are talking a ton about the front end and people are talking a little bit about the back end; but people aren’t talking very much about the middle.

On the front end, you can shorten people’s sentences if you change mandatory minimums and you do any number of other things on sentencing reform — which are all important to do; that’s all good. But somebody being locked up for seven years instead of 15, they’re still locked up for a really long time. That’s still a huge chunk of their life. So I think we need to be talking a little more about what’s happening during those seven years that’s making it so hard for people to get back on their feet once they get out.

A second big concern is [the exclusive focus on] nonviolent offenders.

How so?

Well, now everyone’s like, “Oh, let’s reduce time for nonviolent offenders.” But we’re not going to reduce mass incarceration in this country successfully if we think the only people we need to worry about are nonviolent offenders. Because we’re giving some people who committed, say, an armed robbery when they were 18 like 40 years [behind bars]. And that just doesn’t make any sense.

I know that’s not the case in every state, but right now, our system of justice is incredibly arbitrary. And if we just focus on nonviolent offenders, that’ll get us far in the federal system — that’s about half of all federal offenders — but, overwhelmingly, state offenders won’t be helped. So seeing the policy focus [exclusively on nonviolent offenders], that’s not a good way to start this conversation because then the conversation will end prematurely.

So what is your hope for this book? What would it need to accomplish for you to feel like it was a success on your own terms?

My biggest hope is that lots and lots of people who’ve never thought about criminal justice policy in this country read the book and realize that it could be them — or it could be their son or daughter — and think real hard about sentencing policies, about operations inside of prisons, and about reentry. And I hope they either decide to encourage their companies to ban the box; or contact their legislator to tell them they support giving people a second chance; or just let politicians know that it’s not only incarcerated people who care about this stuff, and that all of society has a stake in this.