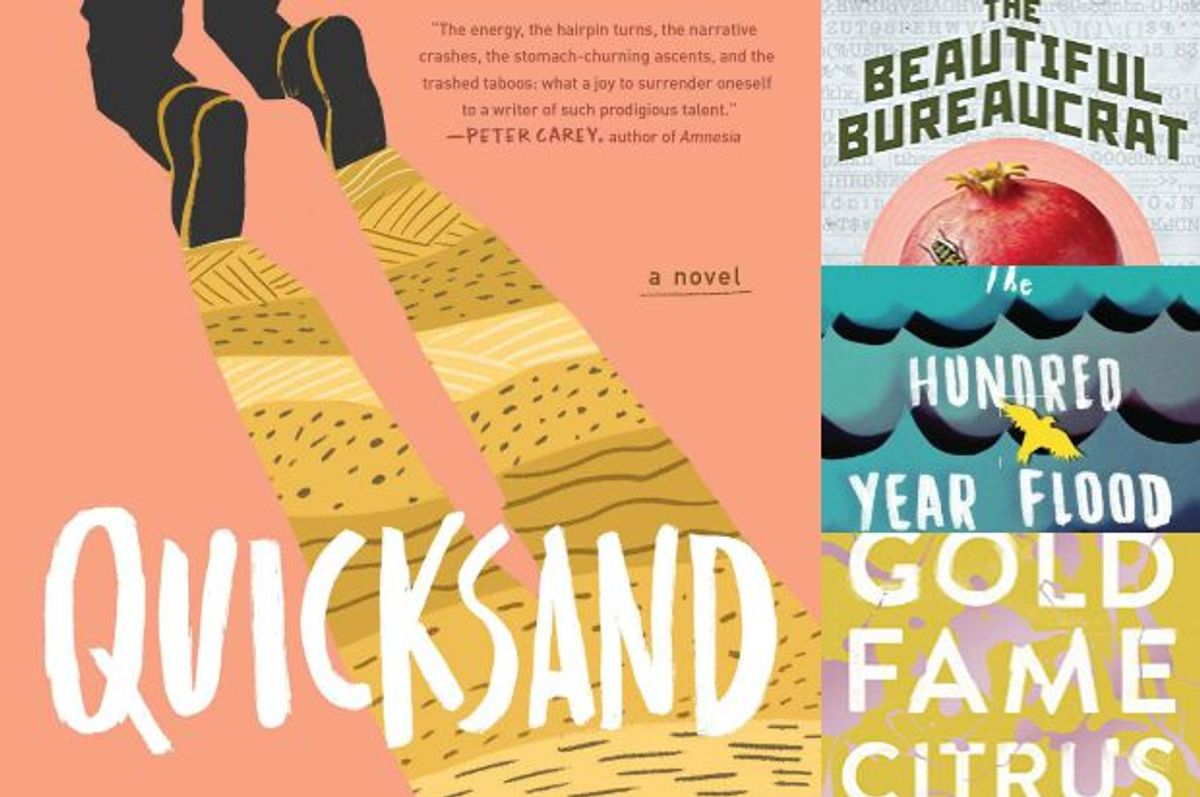

For September, I posed a series of questions – with, as always, a few verbal restrictions – to six authors with new books: Lauren Groff ("Fates and Furies," Sept. 15), Alexandra Kleeman ("You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine," out now), Helen Phillips ("The Beautiful Bureaucrat," out now), Matthew Salesses ("The Hundred-Year Flood," out now), Steve Toltz ("Quicksand," Sept. 15), and Claire Vaye Watkins ("Gold Fame Citrus," Sept. 29).

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

TOLTZ: Suffering, fear (mainly fear of suffering), pathological entrepreneurialism, the absurdity of endurance, the stubbornness of personality, art, exhaustion, inspiration, paralysis, self-exile, immortality, friendship and the question: Is bad luck self-harm by another name?

PHILLIPS: The way the biggest questions about existence play out in the daily grind of work life and home life.

SALESSES: Myth, adoption, ghosts, desire.

WATKINS: Pioneers, movement and the limits of our empathic imaginations, meaning the stuff of life we are probably incapable of truly imagining, e.g., geologic time, earnest mysticism, hexes, cryptozoology, becoming a parent.

KLEEMAN: My book is a missing-persons case told from the perspective of the missing person. It's about what it's like to try to live happily within late-stage capitalism, and whether there's anywhere to escape to when that project fails.

GROFF: Marriage, creativity and female rage.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

WATKINS: The California Water Wars, Manzanar (the Japanese-American internment camp in the Owens Valley), Chinatown, wanting to write a plotty novel where the main character was a sand dune, nuclear-waste storage facilities at Yucca Mountain and Onkalo.

KLEEMAN: I was influenced by everything—books, television, shopping malls, parking lots, ad banners on websites. I empathize with amphibians—my skin is extremely permeable to the outside world.

SALESSES: Prague, people I met in Prague, Korea, adoption, ruins, family, fatherhood. Once as a kid I saw a blue glow near my bed. I walked with my back against the wall whenever I was home alone.

PHILLIPS: Sitting at a desk in a windowless office doing data entry. A two-month period when my husband and I had to move from sublet to sublet. The Forer effect. Waiting on the subway platform on the first cold day of fall when all your warm clothing is in storage. Watching old men fish in the dirty lake in Prospect Park. No longer having 20/20 vision. Population statistics.

TOLTZ: Hospital waiting rooms. Internet comment boards. TV news cycles. Boredom. People I know. People I don’t know. People I can’t believe exist. People I eavesdrop on.

GROFF: Some nights, at dinner, I think so hard about what I'm working on I don't notice my husband or kids or the fact that I'm eating.

Once, while having drinks with my best female friends, I looked around and thought, "Oh my god, they're all so full of rage."

The sound of strings tuning up before an opera starts always makes me cry.

The happiest moments of my life are happy only in retrospect; in the moment, I am always wretchedly uncomfortable.

I wake up in the middle of the night and look over at my sleeping husband's back and feel an existential desolation because I do not know who this man is, will never know, really, who he is, he is a stranger, we do not know each other. The feeling presses down on me physically, like a very heavy rock, but vanishes by morning.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

PHILLIPS: Miscarriage, birth of daughter, death of sister, birth of son.

WATKINS: Too much time alone on I-80. Amish country, coal country, fracking country. Second-trimester mojo.

TOLTZ: Birth of my son and child-rearing. Moving continents three times. Trying to convince myself that writing isn’t an untenable career-choice. Six months of country living in France (that’s goat's-hoof-nailed-to-the-neighbor’s-door-to-warn-away-gypsies-who-stole-other-goat type of country living). Quitting smoking (10 years earlier, but still on my mind). Reevaluating sugar. A host of other things not fit for digital print. Sitting.

SALESSES: Reconstruction of self.

GROFF:

5 a.m.: wake up, coffee, work on stories

6:30: gym or run

8: shower, dress, two fried eggs with sriracha, more coffee, horoscope

8:30: work on book

11:30: lunch of leftovers, sadness

12: faff about

12:30: pretend to work on book or read, check horoscope to see if it could have changed, email, do business

2:15: leave to pick up my sons from school

2:45: joy

8:30: asleep, with a book, with the lights on

KLEEMAN: Coffee, toast, moving back and forth across the country.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

GROFF: ... That's the worst: ...

TOLTZ: "Despise" is too strong a word. The only thing that almost seems worth getting bothered over is when reviewers mention my "obvious" influences and then list writers I’ve never read.

WATKINS: Gritty, unflinching, post-apocalyptic, like a man, Charles Manson.

KLEEMAN: I like all the words they use; the only word that irritates me in reviews is "luminous." My favorite review was by a reader who gave me one star. It ends "The writing is good, though. Sometimes I felt like I was watching a David Lynch film."

SALESSES: People have called it "hard to get into," because the opening moves through time. One reviewer (on Amazon) said it was harder to read than the "Silmarillion." One of the critiques was that it was "too much of a good thing." My feeling: treat yourself.

PHILLIPS: The instant I get the sense that a reviewer or Internet commentator is about to say something devastating about my work, I stop reading. Thin skin.

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

SALESSES: Stay-at-home dad.

KLEEMAN: I'd be a doctor, someone specializing in one particular body part or system. I think it would be fun to fill my head with knowledge about just one of the parts, to have my life become intricately centered around, say, the kidney. Then when I walked down the street I'd see all the people who passed as kind of vehicles for their fascinating, familiar kidneys, and I'd feel more connected to them in that way.

WATKINS: Easy: I would run a life-coaching consultancy with my husband called “Get Your Shit Together! With Derek and Claire.” Derek would handle all the logistics of life administration—improving client’s credit score, setting up automatic bill pay, having stamps on hand, installing little hooks for your keys. I’d handle the social-emotional realm: how to fortify boundaries against vexing family members, phasing out frenemies, excuse Rolodex, the art of the Irish goodbye. Picture "The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up" meets Jay Z’s “Dirt Off Your Shoulder.”

PHILLIPS: Midwife.

GROFF: I would be the head gardener for a huge potager at a chateau in France.

TOLTZ: Conceptual artist/con man.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

KLEEMAN: I think I'm strong at description, internality and brief, punctuated bursts of funny dialogue. I'd like to get better at writing externality, and longer stretches of serious, sustained dialogue. Also, I've always wanted to create a genuine, thrilling plot twist, maybe revolving around mistaken identity or murder! That's a real goal of mine.

PHILLIPS: Envisioning alternate worlds and evoking uncanny images comes naturally. Much harder for me is creating the plot that will take place on the stage I’ve set.

WATKINS: I’m rotten at dialogue. I hate writing narration, especially explicit action -- stage directions bore me. I’ve come to mistrust the present tense. As for strengths, I’m pretty good at describing dirt. Also sand.

GROFF: I feel a lot. I love sentences and people. But I would like to be better at everything.

SALESSES: One of the best compliments I've ever gotten was from a poet I deeply respect who said I had a natural talent for metaphor. I revise A LOT. I have some handle on structure and style. I have to work hardest at characterization. I don't care for description or back story.

TOLTZ: With medium effort: thinking on the page. Dialogue. Noting the absurd. Generating story ideas. Creating characters. With enormous effort that leaves me sweating: structuring the narrative and physical descriptions of characters, action and place. If I could, I’d like to minimize false starts. And become a whole lot better at conceiving smaller stories that could be written in no more than two calendar years.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

TOLTZ: I do this in a number of ways. 1. By continually mistaking me for someone else. 2. By realizing that being a writer is an indispensable role in society, like a fishmonger, or a village idiot. 3. By accepting that I’m a town crier in a town full of town criers. 4. Hubris comes before the fall, they say, so I contend with the hubris by buckling up for the fall. 5. When I write I put the reader out of my mind in the same way that when I eat sugar, I put the dentist out of my mind.

KLEEMAN: Every time I catch myself thinking that I deserve some sort of attention for my book, I remind myself that I would have written it no matter what, I couldn't stop myself from writing it. It's something I ultimately did for myself. But if it reaches past myself, if I find other people through it who feel some of the same things I do—that's wonderful and amazing.

PHILLIPS: I guess it is hubristic but it doesn’t feel that way—it just feels like desperately trying to find an articulation for the primal shriek, hoping there are some listeners on the other end with whom the sound will resonate.

WATKINS: Acknowledging that this may be an elaborate coping mechanism itself, I don’t actually believe anyone cares about what I have to say. At least I hope not because I don’t write with something to say—I’m not running a flag up a pole. I’m a hedonistic writer (and reader). I do it for the pure pleasure of rolling around in language, gossip, seeing other minds on display, traveling to other worlds, my own crackling synapses, etc., etc. Meaning, depth, the invitation to interpret, these are just happy side effects of that pleasure. If I had “something to say” I’d write a pamphlet.

SALESSES: Oh, it's not too hard. I live in a country that doesn't usually value me or my experience except as diversity.

GROFF: Exactly.

Shares