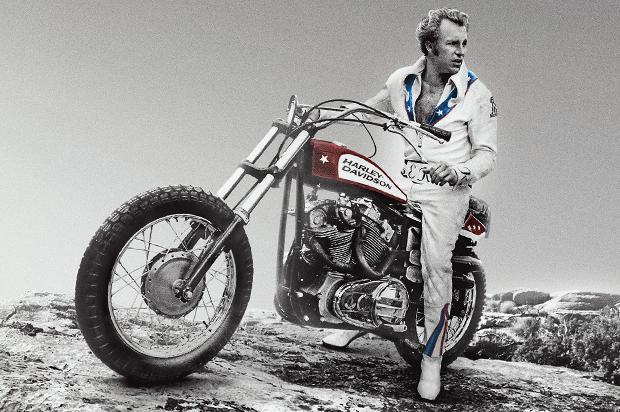

The post-ironic philosophy The New Sincerity doesn’t have a clear definition, beyond being post-ironic. It also doesn’t have obvious exemplars. Those who have been called new sincerists range from Wes Anderson to Kevin Costner, from Bronies to David Foster Wallace. In a 2006 manifesto on The New Sincerity, public radio host Jesse Thorn cited another example—Evel Knievel.

“Let’s be frank. There’s no way to appreciate Evel Knievel literally. Evel is the kind of man who defies even fiction, because the reality is too over the top. Here is a man in a red-white-and-blue leather jumpsuit, driving some kind of rocket car. A man who achieved fame and fortune jumping over things. Here is a real man who feels at home as Spidey on the cover of a comic book. Simply put, Evel Knievel boggles the mind.

But by the same token, he isn’t to be taken ironically, either. The fact of the matter is that Evel is, in a word, awesome. His jumpsuit looks great. His stunts were amazing. As he once said of his own life: “I’ve had every airplane, every ship, every yacht, every racehorse, every diamond, and probably, with the exception of two or three, every woman I wanted in my lifetime. I’ve lived a better life than any king or prince or president.” And as patently ridiculous as those words are, they’re pretty much true.”

This isn’t Knievel’s only contradiction. As a stuntman, Evel Knievel was fantastic—a savvy and nearly unparalleled showman. But as a man, he was often despicable—a philandering, hard-drinking, good-old boy who reportedly forced actor George Hamilton to read a script at gunpoint, and later beat a promoter with a baseball bat over an unflattering book. Knievel’s showmanship made him a symbol of his time, and an American icon. As an icon, what Knievel represented is, in hindsight, equally as troubling as the entertainer himself.

In the last year, two documentaries have tried to make sense of Knievel’s legacy—2014’s “I Am Evel Knievel” and the new “Being Evel,” released in theaters last last month. Many of the same talking heads appear in both, but the way the two films diverge shows just how hard it is to critique our idols.

It’s no great challenge to tell the story of Knievel’s life, and it takes almost no effort to make it seem symbolic. Raised by his grandparents in Butte, Montana, Robert Craig Knievel was a hardscrabble kid who wanted something more than orphan life in Butte could offer. Interviewees in both movies say he was a con man before he was a showman. He allegedly committed crimes and cracked safes (a jail officer first called Knievel “evil”). The turn, it seems, came when he went straight, selling insurance. Knievel the insurance agent broke sales records through a combination of charm and smarts. He reportedly told the company president he would break every record on the books if he could be made vice president after. When he didn’t get his wish, Knievel quit and started selling motorcycles. This was his last regular job.

In 1965, Knievel attempted to make a bit more money by putting on a show. He would, on a motorcycle, jump an assortment of cougars and snakes. He didn’t make it. Eyewitnesses in the new documentary “Being Evel” tell of an audience running from snakes unleashed by Knievel’s motorcycle, while the man himself preened and waved.

Bob Knievel had released more than snakes.

The jumps grew bigger, the failures more injurious, and the jumpsuits more patriotic. Both movies praise the soon-to-be red, white and blue-clad Knievel as a salve on a frustrated nation’s friction burns. The obligatory footage of Vietnam and civil rights marches (one movie sets them to the tune of the more-obligatory “Season of the Witch”) plays as various friends and followers of Knievel talk about how a man jumping a Harley Davidson over fountains in Las Vegas gave America something more real than the footage of war broadcast nightly on television. Ironically, in a time when images of death were flashed into every American home like never before—images of Americans dying for an American cause—the country simultaneously focused on watching to see whether a man dressed in stars and stripes would kill himself for entertainment.

“Nobody wants to see me die,” one Knievel quote goes. “But they don’t want to miss it if I do.”

Knievel later came to represent a certain type of conservatism in early 1970s America. Though he wasn’t Southern, he was rural at a time when rural and Southern identities were fusing and the old South was being plowed over by new industry. “Knievel appeared to many observers as a relic of a dying way of life, the ‘last of the white boys,’” writes historian Bruce Schulman in his book “The Seventies.” Knievel, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Hank Williams Jr. and a handful of other entertainers modernized the imagery and swagger of the old South, while the new South sought to distance itself from good old boys and Jim Crow.

And what a good old boy Knievel was. The term was even popularized (but not invented) in Tom Wolfe’s 1965 Esquire article about another rural motorsports hero, stock car racer Junior Johnson. Like Johnson, Knievel took something that already existed and made it faster, louder, more extreme. And this, somehow, made it more American. The South may have been turning away from its old image, but others were turning away from free love and hippies. One news report says of Knievel, “He’s no ‘Easy Rider’.”

As a symbol, “Evel Knievel was the ’70s,” proclaims Johnny Knoxville in the opening of “Being Evel,” which he also produced. And who better than Knoxville, creator of MTV’s “Jackass,” to tell this story? Even without the production credit, Knoxville would be an obvious choice for an interview — the influence is clear. Knoxville’s failure rate of stunts is purposely higher, but he’s a direct descendant of Knievel the showman and Knievel the Everyman.

Knoxville clearly loves Evel, but the movie challenges this love. While discussing the sheer awesomeness of extreme motorcycle jumps, Knoxville is giddy. But when it comes to the darker side of hero worship, Knoxville is more muted.

Knievel’s end began in 1974. He planned to jump the Snake River Canyon in Idaho. He’d wanted to jump the Grand Canyon, he says, but the secretary of the interior forbade it. “I told him to get hosed and bought my own canyon,” Knievel said in an interview, cleverly wrapping the notions of freedom, land rights and anti-bureaucratic sentiment into one sound bite.

In “Being Evel,” the bacchanal surrounding the jump is called the “evil twin of Woodstock.” But in a way, it was the culmination of everything Knievel’s image quietly supported. Bikers, Hell’s Angels (with whom Knievel had a long feud), and a general crowd of neo-good-old-boys gathered to get hammered and watch a man ride a rocket over a hole in the earth. Beer trucks were toppled, women were assaulted, and, through all this, a high school marching band played patriotic tunes (members of the band are interviewed in “Being Evel,” and they recall the events with sheer terror).

The jump was absurd. Knievel was to ride a steam-powered rocket across the canyon, earning millions in television rights in the process. The jump failed. The rocket’s parachute deployed on takeoff and Knievel safely landed in the bottom of the canyon. There’s some dispute over whether this was an actual mechanical failure, or if Knievel—accidentally or not–pulled the chute early.

Later, when the event’s promoter wrote a warts-and-all authorized book about the jump and the tour preceding it, Knievel broke the author’s arms with an aluminum bat. Evel pleaded guilty in court. He want to jail. It was called frontier justice. Knievel’s career never fully recovered. He divorced. He remarried. He found God. He died as a hero in 2007, after being re-embraced by the extreme sports community he helped create.

The two documentaries diverge at the beating. “Being Evel” plays audio recordings of events that went into the book, collected by the author, Sheldon Saltman. Interviewees condemn Knievel for the attack and say Saltman’s book “Evel Knievel on Tour” is accurate. In “I Am Evel Knievel,” however, the attack isn’t endorsed directly, but it is supported and sympathized. Saltman is described as doing the “lowest thing” by spilling secrets. It’s told he “deserves” what he got.

The difference, perhaps, is in who is saying this. Like any reasonable documentary, “I Am Evel Knievel” relies on stories from Knievel’s family and people who worked with him at various times, but it also features Matthew McConaughey (who befriended the stuntman before his death) and Guy Fieri. Fieri’s presence is particularly surprising, but also oddly perfect. Here is a man who also glorifies an America that isn’t really sustainable and perhaps never really existed—a showman draped in a form of realness that is both unreal and unreachable by the audience. When Fieri says of Knievel “the man knew how to hype the game,” it’s clear it’s coming from a man who also knows.

It’s hard to question our heroes. Perhaps Fieri can’t—or simply doesn’t want to—deal with the darker details. Nuance isn’t really part of his show. Knoxville, though, a decade out from his role in the “Dukes of Hazzard” movie, seems split. “He’s still a superhero,” he says. “You need your heroes.” But he also admits, “I didn’t know the story of the man. It’s pretty complex.”

And Knoxville seems to show some hint of concern at realizing he’s part of that complicated legacy. Knievel’s shadow hangs over extreme sports. But it’s also in the culture at large. Schulman writes that “southern white culture did not crash” into the Snake River Canyon, “it survived and flourished, promoting a mainstream, modernized version of itself. A transformed, commercialized southern white spread across the country, finding new resonance and influence…”

Fieri’s presence in a movie praising Knievel is ironic. Knoxville’s seems sincere. Since the first stunt was televised, there have been critics saying it’s dangerous to copy Knievel and his ilk. Kids try to redo stunts they see on “Jackass.” People eat the food Fieri celebrates. But it’s hard not to love a man in a rocket car, and it’s hard not to cheer when, after replaying crash after crash after crash, the movies show a red, white and blue streak landing safely on the other end of a line of buses.

The difference between admiring and worshiping, between celebrating and sainting, though, is knowing when to pull the chute.