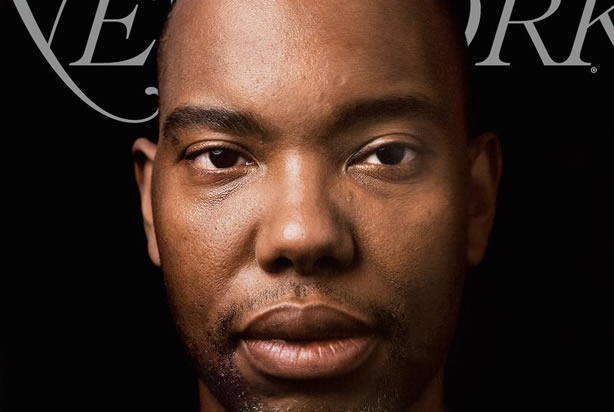

On Monday, Ta-Nehisi Coates published an essay in The Atlantic titled “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration.” It’s a remarkable piece, both in terms of its scope and its depth. Like Coates’s recent essay on reparations, this one feels urgent and destined to explode false narratives about race, crime and America’s justice system.

Focusing on the plight of the black family, Coates analyzes a host of interrelated problems: crime, the Drug War, the perverse prison-industrial complex, and the legacy of America’s racist and kleptocratic past. Coates covers a lot of ground, and I can’t possibly do justice to his argument here, but there are a few things worth highlighting.

When people talk about crime in the inner city, the discussion is typically heavy-handed and bereft of context. The arguments you hear, especially on the right, sound a lot like David Brooks’s musings on morality and poverty: They’re self-satisfied, condescending, and blind to structural inequities. It’s often a variation of the “bootstraps” argument, full of lofty language about self-reliance and personal accountability.

The truth is that crime and poverty are complicated social problems that can’t be reduced to a single variable like ethnicity, birthplace, immorality, or familial disorder. For black people in America, it’s even more complicated (but not at all mysterious). Human beings, after all, are conditioned creatures. You can’t assess a problem like crime or the concomitant breakdown of the family in isolation. “Families,” Coates writes, “are social structures existing within larger social structures.” So it matters a great deal what those larger structures are, and how they got to be that way.

As it happens, black Americans are born into a system founded in white oppression and slavery and government-sanctioned plunder. These distant sins aren’t really distant; they’re very much a part of our living history. Coates traces this history and shows how it echoes in the present – in socially engineered neighborhoods, in the children of black Americans who were denied educational opportunities and home loan programs, and in the absence of generational wealth.

In this essay, Coates focuses on America’s history of using racist tropes to jail black bodies and dismantle black families. His story of modern mass incarceration begins with Daniel Moynihan, the public intellectual, later a senator from New York, who in 1965 published a report entitled “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.” This report, which was delivered to President Lyndon Johnson, candidly addressed the impact of historical and institutional racism on the black family. Moynihan, Coates notes, “argued that the federal government was underestimating the damage done to black families by ‘three centuries of sometimes unimaginable mistreatment’ as well a ‘racist virus in the American blood stream.'” This conclusion was problematic, though, because it undercut racist narratives about black brutishness and criminality. For that reason, Coates argues, the report was misinterpreted and, in the words of journalist Mary McGrory, viewed “as a condemnation of the failure of Negro family life.”

Rather than redress the injustices done to black Americans via a proposal called The Family Assistance plan, as Moynihan later recommended, policymakers thought it wiser (read: more politically expedient) to create a prison state. Coates writes:

From the mid-1970s to the mid-’80s, America’s incarceration rate doubled, from about 150 people per 100,000 to about 300 per 100,000. From the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s, it doubled again. By 2007, it had reached a historic high of 767 people per 100,000, before registering a modest decline to 707 people per 100,000 in 2012. In absolute terms, America’s prison and jail population from 1970 until today has increased sevenfold, from some 300,000 people to 2.2 million. The United States now accounts for less than 5 percent of the world’s inhabitants—and about 25 percent of its incarcerated inhabitants. In 2000, one in 10 black males between the ages of 20 and 40 was incarcerated—10 times the rate of their white peers. In 2010, a third of all black male high-school dropouts between the ages of 20 and 39 were imprisoned, compared with only 13 percent of their white peers.

The disproportionate jailing of black men (propelled by an overtly racist drug war) has wreaked havoc in black communities. It has created more unemployment, more one-parent households, more poverty, more societal instability – the very things that facilitate crime and therefore the illusion that more jails are needed. There’s an insidious circular logic to all this, and it falls predictably on black America.

The long-term effects of mass incarceration are devastating and compound with each generation. “These consequences for black men have radiated out to their families,” Coates writes. “By 2000, more than 1 million black children had a father in jail or prison – and roughly half of those fathers were living in the same household as their kids when they were locked up. Paternal incarceration is associated with behavior problems and delinquency, especially among boys.” As for the convicts themselves, release from prison offers a new kind of unfreedom. “Banishment continues long after one’s actual time behind bars has ended, making housing and employment hard to secure,” Coates concludes. The story of mass incarceration is thus the story of how an entire class of citizens have been systematically excised from American life.

Observers often say the criminal justice system isn’t working; that harsher sentences and bigger jails aren’t meaningfully reducing crime rates. That’s true, but, as Coates suggests, it’s also missing the point. The system is working as designed, and that’s the problem. Capitalist bandits have erected a massive prison-industrial complex and are profiting from racist assumptions embedded in our law and body politic. The government, it can’t be said enough, isn’t particularly interested in less crime or more robust inner cities. Building bigger jails has long been America’s non-solution to its “race problem.” And it’s working its racist will on large swaths of black America, with crippling results.

If Coates’s article accomplishes anything, I hope it changes the way we talk about race and crime and justice. There’s a tendency to analyze these things in a vacuum, without any consideration of antecedent causes. It’s easy to look at crime as simply a choice, but it’s more complicated than that. Social structures matter. The environment matters. History, above all, matters. If we want to reform our justice system (and we should), we need an honest conversation about the past and its relation to the present. And that’s what Coates’s essay is about, and it’s why you should read it.