I emailed Jill Bialosky after letting her new novel, “The Prize,” sink in for a few days, wanting to be sure I was not reacting to the moment—like a love at first sight that fails you not long after.

Here’s what I wrote:

When Isaac Singer was asked if he liked Proust, he answered, “Does he make you want to turn the page?” “The Prize” is a novel whose pages I turned and couldn’t bear to pause, to take a break from reading. At the deepest level—the level of literature—the suspense came from wanting to know the fate of the characters.

I loved your protagonist, the art dealer, Edward Darby. I worried about him, about his marriage, and his middle-age attempt at a fresh start via a fresh love. I worried about the success or failure of his professional life. You have given Edward a rich interior life, one that contends with sink or swim business—after all, the art world is a business, however it is sugared. Or another way of saying it: How does one—does Edward—remain ethical in a tank of less than ethical sharks?

“The Prize” portrays the art world to perfection. Not just the feel of the moment, its speciously glamorous, quotidian anthropology, which you so sharply and economically bring into focus, but the sense, the greater and more profound sense, that the art world is a metonym for our wider world. The art world is also the publishing world, with its concern for stars and big sales. Edward could also have been an editor in a major publishing house.

All this is perhaps too intellectual because it does not approach the mood that the book has left me with: A sense of loss but not defeat; a sense that I have learned more about life than I had thought I knew before I turned your pages.

The art world is the novel’s pool in which your characters sink or swim, and where their character is tested. But “The Prize” also is deeply a novel about love, romantic desire, about marriage and its dissolution. About midlife crisis. There is a question buried here, can you find it?

It is a pleasure to be in conversation with you about “The Prize.” As you well know, I edited your novel “The Green Hour” and also your book of stories, “Self Portraits.” Both these awe-inspiring works also take art and love as subjects. I couldn’t have written “The Prize” at an earlier time in my life. It represents years of my thinking about art, betrayal, marriage, desire, love and integrity, and the way in which the past shapes the present. It is also about how professional lives shape and affect personal life. The two are intertwined. I grew up in a suburb in Cleveland, Ohio, in a modest home. Art was always at the periphery of my life. My first visit as a child to the Cleveland Museum of Art was transformative. I loved getting lost in the paintings and thinking about history and the way in which paintings can be a conduit. When I first moved to New York City 30-some years ago I was a young poet straight out of the University of Iowa’s Writer’s Workshop. It was a shark tank and I quickly learned that there were two kinds of writers, those who were writing out of need and necessity and those who had grander ideas about the role art should play in their own lives. When I look back I think the seeds of this novel were germinating then. Since then I’ve lived and worked in New York City at the crossroad of where art and commerce converge. It’s palpable and continually fascinating. And you’re right, the novel, while also being set in the art world, is at its heart about a long marriage and the way in which an outsider threatens the marriage. I’ve juxtaposed this more conventional marriage with a marriage between two ambitious artists. I’ve been fascinated by “power couples.” We see them everywhere, in every field whether the art world, publishing, politics. I wanted to look at these very different marriages side by side, the rewards and the fallouts. You know, a novel is like a painting. It gets more complicated with each layer.

Your portrait of Edward and Holly’s a marriage goes to the heart of the decline of many if not all marriages of some duration. There is no one to blame; there are no villains, only the wearing down of emotions once vibrant and young. How did you compress so much of a world and so much wisdom in such a brief space?

That’s a wonderful compliment coming from a writer whose sentences are lyrical but also deeply nuanced. I mentioned that I graduated from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop with an MFA in poetry. Before that I received an M.A. from Johns Hopkins University in poetry. It was through poetry that I learned about craft. I never took a fiction workshop or studied the craft of fiction. I learned to write a novel through intense reading and thinking about the way in which a novel is made and constructed and, of course, by trial and error. But I think my background as a poet, the way in which each word counts, sound, how to infer meaning through metaphor, texture through description and scene, informed my prose. Writing a novel is not all that different from writing a poem. At the end of the process everything should cohere. And, of course, any wisdom or acquired knowledge in a work of fiction, a poem or a work of art comes from experience, and being sharply attuned. At the heart, I am a listener and a thinker—an introvert with curiosity. The joy of writing a novel, of making any sort of art, is watching the way in which art can reflect or mirror reality even in abstraction.

How are you so knowledgeable about the art world, its gallery politics, the competitive fierceness among artists, and the glamour, genuine or otherwise, of the whole New York and international art scene? What was your entry point into the art world other than your obvious love for contemporary art? By the way, is this a roman à clef? If so, what is the key?

I mentioned that I’ve always been on the periphery of art as an art lover. I recognized that I had the personality of an artist, the need to create, and the romantic and idealistic sensibility of an artist, but unfortunately I wasn’t very good at it, in the traditional way in which one is taught how to draw or paint in art class. Instead, I found my way through words. But I never lost the fascination and love for art and artists and process. In the past, when I’ve been at residency at Yaddo I met and interacted with visual artists and sculptors and was endlessly curious about their process and pleased to be invited into their studios. I think some of these encounters shaped my understanding about the making of art and also the risks and rewards involved in dedicating one’s livelihood to art. And of course, I read a lot about the art world, went to galleries, art auctions and attended art shows. I’m glad you feel I “got” the art world, as I know your own work has been influenced by your love of art. Here I’m thinking of Poussin in “The Green Hour” and I know about your lifelong friendship and involvement with Roy Lichtenstein and other artists like David Salle, Erich Fischl and April Gornik.

To answer your question, “The Prize” is not a roman à clef. It was liberating to dive into the imaginative world of fiction after I completed my memoir, “History of a Suicide.” Creating fictional characters is a mercurial process. They come to life with each stroke of detail, emotion and characteristic they are given, and the actions they undertake. They’re full of surprises. It’s a wonderful escape to create fictional characters. Of course, aspects of my worldview, my ideals, desires, anguish, go into the creation of every character. I see bits and pieces of myself in all of them.

Were there issues you faced in creating a male protagonist?

I was interested in writing a novel about a male protagonist because of my attraction to the ways in which fiction can be a lens for understanding character. One of my prized novels is Henry James’ “Portrait of a Lady.” I love how James writes about consciousness and the fallibility of character. Isabel Archer is complex and nuanced and as a reader I feel as if I know her completely. The men that surround her are also fairly complex characters and Isabel’s interactions with them all, Lord Warburton, Caspar Goodwood, Ralph Touchett, Gilbert Osmond, shape her sensibility and character. In “The Prize” my intent was to create a genuine male character who was heroic and gentlemanly, even in his failings. I wanted to create a character who doesn’t fully know himself — and I suppose to a certain extent this is true of all of us — and see how he would respond to the trouble I created for him.

One pitfall I faced was in figuring out what my married character would do when faced with his infatuation with another woman. When I initially wrote the novel, Edward did not act on his attraction. One of my early readers, a man, immediately picked this up and questioned it and we both laughed about it. He couldn’t bear not to see Edward consummate his relationship with Julia. I thought about it a lot. It was painful for me to consider that Edward, in a long and complex marriage, would act on his desires and then I decided to put him to the test, and in truth, it made perfect sense that I needed to stack the deck completely and not let him out of his situation by rationalizing that his affair was merely emotional. Action is character and he needed to be responsible for his actions.

This is a novel rich with betrayals, personal, professional, academic, marital, and portrayed without sanctimony. The writer shows; the reader judges. How did you arrive at such aesthetic and personal equanimity?

I recognized at some point in the process of writing the novel that my characters and their actions did not have to be likable or admirable. I could not have written this novel in my 20s, or perhaps even in my 30s, because I was idealistic and lacked sufficient knowledge and experience and was not willing to see the darker side of human nature or believe in it. I’ve witnessed individuals in both my professional life and my personal life who have committed unspeakable acts out of desperation and also individuals who have been extraordinarily generous and conduct their lives with integrity. The role of a novelist, as I see it, is to lay it out there for the reader to make his or her own interpretations and projections.

You’ve been asked this 100 times. I hope you will allow me to be the 101? You are a full-time editor of a major publishing house. In fact, I am one of your authors. You have a family. How do you find time to write?

One of my authors, and it very well might have been you, said that you have to show up every day for the work because if you don’t show up you won’t know what will happen. I try and show up every morning, early, before the demands of the day take hold. Of course, I can’t always, but I do my best. I’m incredibly disciplined, almost to a fault. When I wrote my second novel, “The Life Room,” I told myself that I would wake up every morning and write five pages in my notebook and would not read anything beyond the last two pages I’d written. I followed that course until I had a first draft. This novel was different. It came in spurts and then I put it aside for interrogation, and this process repeated itself again and again. Writing is not a chore. It is a necessity and a delight. I read an interview in the Paris Review recently with John Banville. He quoted Auden with the saying that a writer should be loaded with as much trauma as children as they can bear and unfortunately my childhood was filled with it and writing became a way of reckoning. I feel most myself when I’m writing. But with that said, I have as much a desire to escape from it after I’ve put in my daily hours. I’m intensely self-critical and I never feel as if what I’ve committed to paper expresses the full scope or nuance of what I’d hoped for. The self-scrutiny is tortuous, as much as a delight, and I’m happy to leave it alone and tend to my full life outside of writing. It’s a privilege to work at a publishing house in which its ideals and books we publish match my own expectations of quality and excellence. And it is an honor to work with writers I admire and respect.

Frederic Tuten lives in New York. He has published five novels and a book of interrelated short stories, “Self Portraits: Fictions.” He has won two Pushcart Prizes and a Guggenheim Fellowship for fiction.

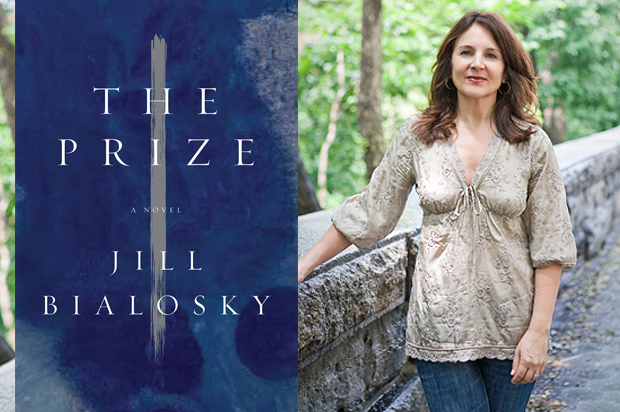

Jill Bialosky is the author of three novels including “The Prize“; a memoir, “History of a Suicide: My Sister’s Unfinished Life”; and four volumes of poetry, the most recent of which is “The Players.” She is an executive editor at W. W. Norton & Co.