“Well, friend, want to go to the shooting range with me?” Clayton said, his light brown eyes lighting up mischievously. We were stretching before the CrossFit class Clayton coaches when I mentioned that I’d recently realized he was my “token conservative friend,” the way some people have a “token black friend.” His response was to invite me to, of all things, a gun range.

I reached for my toes as my liberal gun-control-advocate self immediately and gleefully replied, “Seriously? Of course I do.” Because politics should never, if at all possible, get in the way of fun.

Little did I know that this would be one of several experiences, during what turned out to be the week of the George Zimmerman acquittal, that would make it virtually impossible for me to claim the liberal outrage/moral high ground I would later wish I could maintain, since life and its ambiguities sometimes throw our ideals into crisis.

*

A few days after his offer, I saw Clayton’s short, muscular frame walking up to my front door carrying a heavy black bag. He was there for a quick gun-safety lesson before we headed to the range, since I had never in my life actually held a handgun. Clayton is a Texan, a Republican, and a Second Amendment enthusiast. But since Clayton has a degree from Texas A&M and has lived part of his life in Saudi Arabia, where his dad was an oil man, he describes himself as a “well-educated and well-traveled redneck.”

“There are four things you need to know,” Clayton said, beginning my very first gun-safety lesson. “One, always assume every gun you pick up is loaded. Two, never aim a gun at something you do not intend to destroy. Three, keep your finger off the trigger until you are ready to fire, and four, know your target and what’s beyond it. A gun is basically a paperweight. In and of themselves,” he claimed, “they are only dangerous if people do not follow these rules.”

I’m not sure what the statistics are on gun-shaped paperweight deaths, I thought, but I’ll be sure to look that up.

“Okay, ready?” Clayton asked.

“I have no idea,” I replied.

He placed a matte black handgun and a box of ammunition on our kitchen table, and it felt as illicit as if he had just placed a kilo of cocaine or a stack of Hustler magazines on the very surface where we pray and eat our dinners as a family.

I tried to ask some intelligent questions. “What kind of gun is this?”

“It’s a 40.” Like I had any idea what the hell that meant.

“What’s a 9mm? I’ve heard a lot about those.”

“This is.” And he lifted his shirt up to show his concealed handgun.

“Man, you don’t carry that thing around all the time, do you?” He smiled.

“If I’m not in gym shorts or pajamas, yes.”

Later, in the firing-range parking lot, filled almost exclusively with pickup trucks, I made the astute observation, “No Obama bumper stickers.”

“Weird, huh?” he joked.

When I’m someplace cool, say an old cathedral or a hipster ice cream shop, I am sure to check in on Facebook. But not here. Partly because it was Monday morning and Clayton had penciled in our fun shooting date as a “work meeting,” but also because I didn’t want a rash of shit from my friends or parishioners— almost all of whom are liberal— asking if I’d lost my mind or simply been abducted by rednecks.

As we stepped onto the casing-littered, black rubber-matted floor of the indoor firing range, I was aware of several important points: one, our guns were loaded and intended to destroy the paper target in front of us; two, I should put my finger on the trigger only when I intended to shoot; three, a wall of rubber and concrete was behind my target; and four, I sweat.

I knew from hearing gunshots in my neighborhood that guns were loud. And I knew from the movies that there was a kickback when a gun was fired. But, holy shit, was I unprepared for how loud and jolting firing a handgun would be. Or how fun. We shot for about an hour, and after we were done, Clayton told me that I did pretty well, for a first-timer. (Except for when a hot shell casing went down my shirt and I jerked around so mindlessly that he had to reach over and turn the loaded gun in my hand back toward the target, making me feel like a total dumbass. A really, really dangerous dumbass.)

But I loved it. I loved it like I love roller coasters and riding a motorcycle: not something I want in my life all the time, but an activity that is fun to do once in a while, that makes me feel like I’m alive and a little bit lethal.

“Can we shoot skeet next time?” I asked eagerly as we made our way back to the camo-covered front desk to retrieve our IDs. The whole shop looked like a duck blind. As though if something dangerous or tasty came through the front door, all the young, acne-ridden guys who work there could take it down without danger of being spotted.

On the way back to my house, I suggested we stop for pupusas (stuffed Salvadorian corn cakes) so that we both could have a novel experience on a Monday.

Sitting at one of the five stools by the window at Tacos Acapulco— looking out on the check-cashing joints and Mexican panaderias that dot East Colfax Avenue— I took the opportunity to ask a burning question: “So why in the world do you want to carry a gun all the time?” I’d never knowingly been this close to a gun-carrier before, and it felt like my chance to ask something I’d always wanted to know. I could only hope my question didn’t feel to him like it does to our black friend Shayla when people ask to touch her afro.

As he tried managing with his fork the melted cheese that refused to detach itself from the pupusa, he said, “Self-defense, and pride of country. We have this right, so we should exercise it. Also if someone tried to hurt us while we were sitting here, I could take them down.”

It was a foreign worldview to me, that people could go through life so aware of the possibility that someone might try to hurt them, and that, as a response, they would strap a gun on their body as they made their way through Denver. I didn’t understand or even approve. But Clayton is my token conservative friend, and I love him, and he went through the trouble of taking me to the shooting range, so I left it there.

*

The week I went shooting with Clayton was also the week of my mother’s seventieth and my sister’s fiftieth birthday party. It was a murder mystery dinner, so, five nights after blasting paper targets with Clayton at the shooting range, I sat on the back patio of my parents’ suburban Denver home and pretended to be a hippie winemaker for the sake of a contrived drama. Normally, my natural misanthropy would prevent me from participating in such awkward nonsense, but I soon remembered how many times I had voluntarily dressed myself up and played a role in other contrived dramas that didn’t involve a four-course meal or civil company (like the year I tried to be a Deadhead), so I submitted to the murder mystery dinner for the sake of two women I love. My role called for a flowing skirt, peasant blouse, and flowers in my hair— none of which I own or could possibly endure wearing, so a nightgown and lots of beads had to do the trick.

Throughout the mostly pleasant evening, I would see Mom talking to my brother out of the side of her mouth, just like she did when we were kids and she wanted to tell Dad something she didn’t want us to know. I watched my mom, unaware that an unscripted drama was unfolding around the edges of the fictional one that called for flowers in my fauxhawk.

As I snuck into the kitchen to check my phone for messages, my dad followed me to fill me in on what was happening. It turns out my mom’s side-of-the-mouth whispers were about something serious. My mom had been receiving threats from an unbalanced (and reportedly armed) woman who was blaming my mom for a loss she had experienced. My mom had nothing to do with this loss, but that didn’t stop this woman from fixating on her as the one to blame. And she knew where my mom went to church on Sundays.

“It’s made being at church pretty tense for us,” my father told me.

My older brother Gary, who is a law enforcement officer in a federal prison and who, along with his wife and three kids, attends the same church as my parents, walked by Dad and me in the kitchen and said, “Horrible, right? The past three weeks I’ve carried a concealed weapon to church in case she shows up and tries anything.”

I immediately thought of Clayton and his heretofore foreign worldview, weighing it against how I now felt instinctually glad that my brother would be able to react if a crazy person tried to hurt our mother. And how, at the same time, it felt like madness that I would be glad someone was carrying a gun to church. But that’s the thing about my values—they tend to bump up against reality, and when that happens, I may need to throw them out the window. That, or I ignore reality. For me, more often than not, it’s the values that go.

My gut reaction to my brother’s gun-carrying disturbed me, but not as much in the moment as it would the next morning.

*

On the night of the party, I missed the breaking news that George Zimmerman, who had shot and killed unarmed teen Trayvon Martin, had been found not guilty on all counts. For more than a year, the case had ignited fierce debate over racism and Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” law, which allows the use of violent force if someone believes their life is being threatened.

My Facebook feed was lit up with protests, outrage, and rants. I wanted to join in and act as a voice for nonviolence that week, but when I heard on NPR that George Zimmerman’s brother was saying he rejected the idea that Trayvon Martin was unarmed, Martin’s weapon being the sidewalk on which he broke George’s nose, well, my first reaction was not nonviolence but an overwhelming urge to reach through the radio and give that man a fully armed punch in the throat.

Even more, that very week, a federal law enforcement officer was carrying a concealed weapon into my mom’s church every Sunday. Which is insane and something I would normally want to post a rant about on my Facebook wall for all the liberals like me to “like.” Except in this case, that particular law enforcement officer (a) was my brother, and (b) carried that weapon to protect his (my) family, his (my) mother, from a crazy woman who wanted her dead. When I heard that my brother was armed to protect my own mom, I wasn’t alarmed like any good gun-control supporting pastor would be. I was relieved. And now what the hell do I post on Facebook? What do I do with that?

I also had to deal with the fact that I simply could not express the level of antiracist outrage I wanted to, knowing something that no one else would know unless I said it out loud: despite my politics and liberalism, when a group of young black men in my neighborhood walk by, my gut reaction is to brace myself in a different way than I would if those men were white. I hate this about myself, but if I said that there is not residual racism in me, racism that— after forty-four years of being reinforced by messages in the media and culture around me— I simply do not know how to escape, I would be lying. Even if I do own an “eracism” bumper sticker.

The morning after the George Zimmerman verdict, as I was reflecting on what to say to my church about it, I wanted to be a voice for nonviolence, antiracism, and gun-control as I felt I should (or as I saw people on Twitter demanding: “If your pastor doesn’t preach about gun control and racism this week, find a new church”) — but all I could do was stand in my kitchen and cry. Cry for all my inconsistencies. For my parishioner and mother of two, Andrea Gutierrez, who said to me that mothers of kids with brown and black skin now feel like their children can legally be target practice on the streets of suburbia. For a nation divided — both sides hating the other. For all the ways I silently perpetuate the things I criticize. For the death threats toward my family and the death threats toward the Zimmerman family. For Tracy Martin and Sybrina Fulton, whose child, Trayvon, was shot dead, and who were told that it was more his fault than the fault of the shooter.

Moments after hearing about the acquittal, I walked my dog and called Duffy, a particularly thoughtful parishioner. “I’m really screwed up about all of this,” I said, proceeding to detail all the reasons that, even though I feel so strongly about these issues, I could not with any integrity “stand my own ground” against violence and racism — not because I no longer believe in standing against those things ( I do), but because my own life and my own heart contain too much ambiguity. There is both violence and nonviolence in me, and yet I don’t believe in them both. She suggested that maybe others felt the same way and that maybe what they needed from their pastor wasn’t the moral outrage and rants they were already seeing on Facebook; maybe they just needed me to confess my own crippling inconsistencies as a way for them to acknowledge their own.

That felt like a horrible idea, but I knew she was right. So often in the church, being a pastor or a “spiritual leader” means being the example of “godly living.” A pastor is supposed to be the person who is really good at this Christianity stuff — the person others can look to as an example of righteousness. But as much as being the person who is the best Christian, who “follows Jesus” the most closely can feel a little seductive, it’s simply never been who I am or who my parishioners need me to be. I’m not running after Jesus. Jesus is running my ass down. Yeah, I am a leader, but I’m leading them onto the street to get hit by the speeding bus of confession and absolution, sin and sainthood, death and resurrection— that is, the gospel of Jesus Christ. I’m a leader, but only by saying, “Oh, screw it. I’ll go first.”

I stood the next day in the copper light of sundown in the parish hall where House for All Sinners and Saints meets and confessed all of this to my congregation. I told them there had been a million reasons for me to want to be the prophetic voice for change, but every time I tried, I was confronted by my own bullshit. I told them I was unqualified to be an example of anything but needing Jesus.

That evening I admitted to my congregation that I had to look at how my outrage feels good for a while, but only like eating candy corn feels good for a while— I know it’s nothing more than empty calories. My outrage feels empty because what I am desperate for is to speak the truth of my burden of sin and have Jesus take it from me, yet ranting about the system or about other people will always be my go-to instead. Because maybe if I show the right level of outrage, it’ll make up for the fact that every single day of my life I have benefitted from the very same system that acquitted George Zimmerman. My opinions feel good until I crash from the self-righteous sugar high, then realize I’m still sick and hungry for a taste of mercy.

*

The first time I was asked to give a lecture on preaching at the Festival of Homiletics, a national conference for preachers, they wanted me to give a talk on what preaching is like at House for All. I wasn’t sure what to say, so I asked my congregation. There was passion in their replies, and none of it had to do with how much they appreciate their preacher being such an amazing role model for them. Not one of them said they love all the real-life applications they receive in the sermons for how to have a more victorious marriage. Almost all of them said they love that their preacher is so obviously preaching to herself and just allowing them to overhear it.

My friend Tullian put it this way: “Those most qualified to speak the gospel are those who truly know how unqualified they are to speak the gospel.”

Never once did Jesus scan the room for the best example of holy living and send that person out to tell others about him. He always sent stumblers and sinners. I find that comforting.

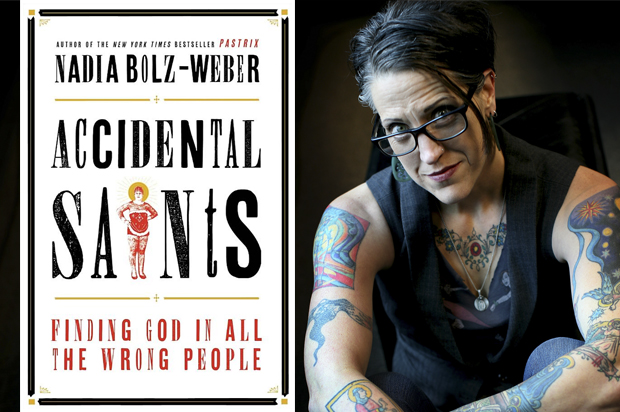

Reprinted from “ACCIDENTAL SAINTS: FINDING GOD IN ALL THE WRONG PEOPLE.” Copyright © 2015 by Nadia Bolz-Weber. Published by Convergent Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.