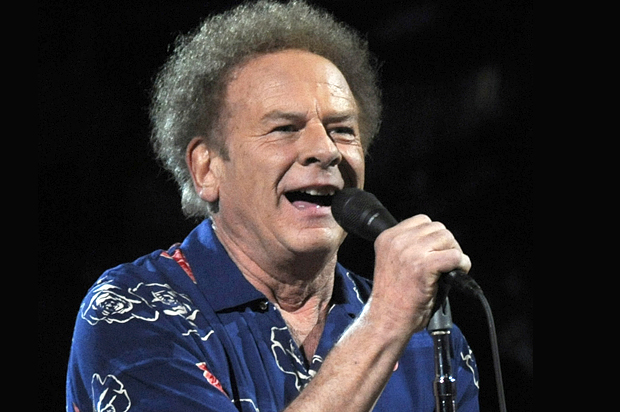

You don’t just interview Art Garfunkel. The singer doesn’t seem to enjoy the rigmarole of press queries and prepared questions, the awkward pauses and rehearsed answers. Promotional Q&As often possess a dry, stilted air, which can get tedious over time. Garfunkel wants none of it. Instead, the singer—most famous as one half of Simon & Garfunkel, but also an accomplished actor and solo artist in his own right—would rather dispense with the formalities and just talk for a while.

So, when I call him up to talk about some of his fall projects, he immediately commands the conversation and directs it off into an odd, new direction.

Art Garfunkel: How do you spell your name? I find that a lot of Stephens are spelled with “ph.” Is that you?

Yes. I’m a ph.

Garfunkel: But you guys pronounce your name as if it’s a V. Nobody says Stefen, do they?

I get Stephan quite a bit. I remember one time I told somebody I was Stephen with a PH. And she wrote down, “Steven with a PH.”

Garfunkel: They’re very different kinds of people. I think that Stephen-with-a-ph is the artist. Steven-with-a-v is more ordinary, but an American ordinary. Like Bob. It doesn’t have that specialness.

The PH definitely gives it a European flair.

Garfunkel: So does your last name. It’s like Garfunkel. A little different.

Garfunkel is the rare celebrity who has aged with his eccentricities intact. He was a kid from the Forest Hills neighborhood of Queens, New York, when he met up with Paul Simon and started a folk duo called Tom & Jerry. Even as Simon sought the affirmation of the then-bustling folk-revival scene, Garfunkel hung back, his blond afro giving him a laid-back demeanor. In old photos he always seems simultaneously intense and easygoing, serious and perhaps a bit stoned. But then he opens his mouth to sing, and out comes that incredible tenor, a gentle, soaring tone that bends and swoops with preternatural agility. It lent Simon’s songs a sense of scope and grandeur that allowed them to transcend and outlive the folk revival. Even so, Simon & Garfunkel didn’t make it out of the 1960s as a duo. As soon as the new decade had begun, they went their separate ways, each embarking on long solo careers.

But Garfunkel does not want to talk about that—or, at least, he does not want to approach the subject of his career directly. He prefers a more roundabout path to the past, one that starts with him asking where I’m calling from, as though the present moment was the most important subject imaginable.

Garfunkel: Where are you now?

I’m in Bloomington, Indiana.

Garfunkel: You know, I walked across America so I got a real feel for the geography. Bloomington’s near the middle of the state, near Indianapolis, right? So this is very American. The land is kind of flat with a little bit of curvature—a very sweet curvature to the land, yes? We think of Bloomington as a college town, correct? So fall means back to school in a very rich way. It’s wonderful, that back-to-school feeling of September. It’s a rebirth. The air gets autumn keen and the spirit sharpens up.

As I mentioned, I’ve walked across the U.S. and now Europe, so I know the land. There are many different version of the land: industrial, wasteland, uninspired land. But campuses are a Walt Disney movie. They’re a dream come true. They’re such a cut above almost all of it. Campuses are so pretty, if only the kids realized it. The rest of the earth is something less than that. The skyscrapers downtown, the used-car lots, the hamburger chains, everything that makes up the normal American scene. But not the campuses. They’re pretty. Those trees…

Garfunkel is given to such flights of fancy, reveries that instill even everyday things with a sense of romance. It’s a curious sensibility, and you get the sense that he hasn’t changed much in the last 50 years. “I’m a guy who comes from a different era,” he says at one point, and he does give the impression of someone preserved in amber, his attitudes and even his voices those of a much younger man. Age and experience have not dulled his sense of curiosity, but only intensified it. So it is only reluctantly that we move on to other matters. He makes himself change the conversation, although he soon strays.

Garfunkel: OK, let’s talk about my boring thing. I have a concert coming up on Oct. 3 at Carnegie Hall. I recently had a show at London’s Royal Albert Hall. And Columbia just released a complete album collection with that other guy. They’re putting all our stuff out on vinyl. Six records. It’s so beautiful. You hold the set in your hands and you want to buy more copies. I called the label and told them to send me more stuff. It’s so buyable. God, we all miss vinyl. We forgot how great it is. It’s so pretty to hold this square with a round record inside of it. There are six of them in this collection. Maybe we can help vinyl come back. This one Columbia set might be a little brick in the edifice. I want to see vinyl happen. That’s what Paul and I and Roy Halee did. We made vinyl records in the ‘60s. That’s my claim to fame.

What else? I have a PBS special that recently hit the air, “The Concert in Central Park” with Paul. And I have a rerelease of my favorite thing of all the things I’ve ever done. “The Singer” is my baby. It’s a two-CD record of me choosing where I think I sound the best on all my work with Paul and without Paul. It’s sequenced so nicely, how it flows in and out of Simon & Garfunkel, in and out of up tempos and slow, how I can hold the listener from line to line to line with good singing. I know my vocals. If you really listen to Artie singing….

[A brief digression: Garfunkel repeatedly refers to himself in the third-person, as though the person who sang on “Bridge Over Troubled Water” is someone different than the man talking to me on the phone. It’s an odd conversational mannerism, but one that is charming and perhaps even necessary for any celebrity to maintain a certain semblance of sanity. But the thought occurs to me: Which is the real person, Art or Artie? And which is the persona? Am I talking to the real person directly, or is he talking to me through a carefully constructed facade?]

Garfunkel: If you really listen to Artie singing, then the set will hold you for these 34 songs. That’s my favorite album, “The Singer.” It was rereleased in England to go with that Albert Hall show. But all of these are commercial ventures that your record company does or that a promoter wants you to do. And I do love my show. I can’t wait to hit the stage and sing those songs. But what really cooks for me at the moment is writing my autobiography. I’ve been doing it for a couple of years. It’s now gathered some real steam and the wheels are chugging along. I know what the next few pages are and I’m very into it. It’s my main preoccupation. I’m a words man now.

Is that a similar art to singing? It seems like both might involve an enormous amount of control and restraint?

Garfunkel: They both have the dance of rhythm—a light, controlled dance like a puppeteer with his fingers holding strings on puppets. He moves the puppets in a dance with gentle motions of the fingers. Both singing and writing have that same quality. Syllables fall exactly where you want them to fall, so there’s flow on the page. I sing the same way. As the line comes out of my mouth, I can move in one-sixteenth of an inch toward the microphone or I can move out, I can press it on a little stronger, whatever the phrase demands.

It’s a busy life right now. I hope my kids understand. Daddy’s having a very good time in his work life, but all they understand is, Is Daddy here or is he gone? I’m 73, Stephen, and I have a 9-year-old son. Talk about spirituality and art. It’s Raphael painting the little Jesus and calling it “Adoration.” To adore. To find your child adorable is a religious place we go to, and if you’re 73, then it’s extremely religious. It’s so beautiful. It captivates you. I’ve had a proud career, but raising my two sons—Arthur Jr., who’s 24, and little Beau, who is 9—is really my daily delight. Every day I write my book, and then I meet my son. I try to get him to kick the ball around with me. Kim [Garfunkel’s wife] and I try to have a dinner that includes him, but he’ll bring that little hand-held video screen that makes me lose his company. It’s the scourge of American life. Do you know about this problem? People keep their noses in their video game devices, and then gone are clouds, the act of looking around, listening to live people and talking with them? You lose your sense of being here on Earth to those little screens. We ought to have a law that makes them illegal. It’s really killing life itself.

And what on those screens could be more interesting than other people?

Garfunkel: Maybe they’re scared. People have always been shy. Never underestimate how much shyness is behind everything. When I made my records, you’d be in the studio and while the technicians were setting up speakers, you’d always have a magazine on the console. You’re flipping pages, too, to be superficially busy while you’re waiting for the next thing to attend to. But with these screens, it never stops. They’re not doing this as a side life while they’re waiting for the next part of life to happen. They just lose what’s going on in real life. And when I look over my son’s shoulders, I just see these shooting games. They should not be allowed. The proportions are all out of whack. But maybe it’s my job to say, You can look at this stuff for two hours, and then you have to put it away. Maybe that’s what’s missing. I’m not being the stern enforcer that I should be. I love them too much. What else was I talking about?

You were talking about “The Singer.”

Garfunkel: Yes. Right.

Is there much overlap between that compilation and the shows you’re doing?

Garfunkel: There are 34 songs on “The Singer” and my show has 17. That’s half the number. My show has both Simon & Garfunkel and solo Artie. “The Singer” is mostly solo stuff, but my live show is 50-50. The obvious songs are well represented, although “The Boxer” is not on my set. Paul took that one. He has a similar album that couples Simon & Garfunkel with his own solo career. Mine’s called “The Singer.” I’m not sure what he calls his.

This sounds like a little joke Garfunkel is playing. Paul Simon’s compilation is called “The Songwriter.” Garfunkel surely knows this, and named his own compilation accordingly.

Garfunkel: We both had to work out which Simon & Garfunkel plums would be on whose album. What fun it was to work that out.

His tone suggests that it was not that much fun at all. You can almost hear his eyes rolling as he delivers that line.

Garfunkel: The live show allows me to be the sensitive singer that I like to be. I can drop the notion that I have to have upbeat numbers. It’s just me and a guitar, so it’s less-is-more taken to the extreme. If you believe in your own vocal as colorful and worth hearing, you only want one guitar. You want a sort of 75/25 volume balance where the vocal is paramount. No place for drums, which can be too strong and clattery. Sometimes a tiny bit of percussion can help “Homeward Bound,” especially on the chorus. Otherwise, you want to leave it up to Artie to hold the audience from one line to the next.

I love my show. It works. Every night the audience eats it up. I do these readings. I fancy myself a writer now, so I do a minute or a minute-and-a-half of reading one of my bits. It holds them. It’s interesting as soon as it begins, because the first line is always a grabber. And they’re grabbed. I try to stay in control from syllable to syllable. It’s a nice dance, that flow of syllables and words. I feel like I’ve got a good touch as a writer, so I weave in a whole bunch of these bits between the songs. I talk about a girlfriend of mine from the past. I talk about my family, and I talk about show business and mortality. What other rock-and-roll artist comes onstage and reads a bit he wrote about dying? I say a lot of sweet and positive things, but I also say some really perverse stuff. Human beings are very funny, complex creatures. We put on our clothes and present ourselves as cohesive individuals, but inside our mental tape is all over the place. We’re all a little bit schizophrenic, so it’s the artist’s job to say, Here’s what it’s really like. Here’s truth. It’s not going to be neat. But you have to do that and you have to hope that everybody else goes, Me too! I’m as odd as you are. Thank you for admitting it, Art.

Garfunkel is no longer conversing. He’s delivering a monologue that happens to be full of dialogue, and he plays all the parts himself. Best to let him go.

Garfunkel: I used to do a Q&A period in my show. Sometimes I still do it. You turn on the lights and there they are. You get the most loving questions. These are all your fans, after all, and I stop being an artist who is chasing after the beauty of the line. I’m a workaholic. I want to control the song and serve it up artfully. But this is a change of gears. You get to be the star that they know and love, and you get to answer these curious questions. I love to see the audience, and I applaud them for their bravery. Just getting up to ask a question, getting the voice to come out of their chest and into the room—only people with guts can do that. My heart goes out to those people who have the gumption to project. And I have a great time addressing their curiosity. I even try to start it off occasionally, if they seem tongue-tied.

All right, I’ll ask the first question myself. Artie, did you ever meet the Beatles? And then I give them the real answer. Yes, I did. Each of the four guys on different evenings, great cherishable memories, and I got into it.

Are you ever going to work with Paul again? And now, Stephen, you’re going to say, Are you ever going to work with Paul again? Because you’re a writer and this is a field of real, basic curiosity.

But is it? Surely this is a defense mechanism, developed after so many interruptions at this point in the story. No, this is a trick question. After taking control of the interview and even turning it inside out by interviewing himself, Garfunkel is now testing me. He’s trying to see what kind of listener and writer I really am. Do I want to make him repeat that canned answer one more time? Or is there really even an answer to that question beyond an evasive “maybe” or a definitive “no way”? Garfunkel is drawing me out. This is a test.

Yes, when are you going to work with Paul McCartney again?

Garfunkel: Now you’re talking! Here’s a journalist I can work with.

Phew.

Garfunkel: Did I ever work with McCartney. Maybe you know better than I do. No, I don’t think I ever worked with him. We spent a little time together socially, but we’ve never made music together. I wonder why. He knows I’m good. He was at a party in the Hamptons, and my wife and son were with me. And he took a shine to Arthur Jr. My boy is a wonderful, wonderful singer. He’s very babyfaced. His sweet, sensitive face goes with a personality that’s got a lot of gumption. He speaks up very well for himself. He and McCartney hit it off, and McCartney sits down at a piano and starts singing, “You’ve got the cutest little babyface.” My kid is no slouch. He’s full of politeness and respect. And he starts singing along. He and McCartney are singing “Baby Face” together. My boy has great pitch.

I might be a bit too intimidated to sing with McCartney.

Garfunkel: Do you know this about musicians? Making music is a place we go to. It’s a real comfort zone. On the Monopoly board, it’s the box marked Go. When you pass go, you get $200. It’s our favorite box. When you go into a song, when you respect your own God-given talent, there’s something automatic about flexing those muscle. You go to that comfort zone and lo and behold, you find other musicians there. That’s the great thing about making music, but it’s also why Paul and Artie can be very squirmy around each other. We’re so damned different, but when the song and the music is happening and Paul is playing guitar—and Paul Simon plays brilliant acoustic guitar—you go to that place comfortably. That’s a good answer, isn’t it?