In 1991 I was a struggling songwriter, teaching tennis in Encino, just up the 101 from Hollywood where I was living in a little studio apartment a couple blocks from Melrose.

My big claim to fame was having given a few tennis lessons to Wilt Chamberlain, who would come to the park on the occasional afternoon. I taught him a nice slice serve. “I gotta practice now,” he said once. “It’s a little intimidating with the coach right here.” Meaning me.

I wrote a few Bukowski-like poems about teaching Wilt. Mostly crazy fantasies about hanging out with him, cruising down Ventura Blvd. “Hey!” people would shout in the avenues of my mind, “Isn’t that Dan Bern and Wilt Chamberlain?!”

In the evenings I would go and play little music gigs throughout Los Angeles. I had a steady Wednesday night spot at a Chinese joint on Fairfax called Genghis Cohen. I played there so much they put my name on the menu. “The Dan Bern Deal.” Szechuan green beans and Mongolian beef. A great combo, “The Dan Bern Deal.”

The guy who ran the club was named Artie Wayne. He had run A&M’s publishing “for five minutes,” in the industry parlance. Legend was that he’d had a lighted dance floor installed in his office. “It ain’t a hit unless I can dance to it!” he’d crow.

Sometimes Artie would mess with me. “Dan,” he’d pull me aside, two minutes before my set, “Bob Dylan’s coming tonight.”

Artie knew I had a serious Dylan fixation. Maybe it was the harmonica rack I wore around my neck. Maybe it was the topical, talkin’ blues songs I sang. Maybe it was my Jewish midwestern roots and my nasal inflections. Maybe it was all of it. Artie knew how to get under my skin.

I’d first been hit by Dylan, hard, when I was about 16. Up til then I’d mostly listened to the Beatles, and whatever happened to be on the radio. Then one day, this older guy, the husband of a co-worker of my Mom’s, played some Dylan records for me. “Here’s ‘Shelter from the Storm,’” he said. “Here’s ‘Blowing in the Wind.’”

Immediately, my cello was toast. I got my Dad to buy me a guitar the next day.

Even so, I didn’t really “get” what Dylan was on about until one summer day a few weeks later when I was home after my paint crew job at the college. I’d smoked a little dope, and was painting the door of my room. I had put “Blonde on Blonde” on the record player.

Suddenly, as “Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat” began churning, I fell fully into the song. It was like Alice stepping into Wonderland. Every line Dylan sang meant something else! Every line was a sarcastic sneer! For the first time I’d heard something that sounded exactly how I felt.

I started writing my own songs. I never looked back. After college I went to Chicago and started playing seven open mics a week. Soon I started to get my own gigs. The Earl of Old Town. Holstein’s. The No Exit. Legendary Chicago folk clubs.

I printed up posters. “Topical and original folk and blues” they said. With a picture of a curly-haired Midwestern Jewish kid with a guitar and a harmonica rack. I was on my way.

Ten years later, having migrated west, I was teaching tennis in Encino and still struggling. But I’d made a little headway. There was a buzz. The junior scouts from the major record companies, with no power to sign but nice suits and offices and business cards, were coming around.

And I had a column in a little publication called “Song Talk.” My column was called “Verse-Chorus-Bridge.” I didn’t do any real reporting. I just made up characters, mostly based on the publishers and songwriters I was running into, and told fanciful tales of trying to make some headway into the cutthroat world of music and songwriting.

One night I wrote a fake interview with Bob Dylan’s mom. I knew her name, so I used it. The Milli Vanilli scandal was fresh in the news, so I made up a “scandal” about Dylan not having actually written his songs. Turned out, I said, that his mom had written all of his songs. And I “interviewed” his mom. To great comic effect, I thought. They printed it, I had a laugh, and forgot all about it.

Time rolled along. I almost had a record deal with Chameleon, an offshoot of Warner Bros., but it fell through. I got frustrated hanging around L.A. trying to get a record deal. I let go of my apartment, sold my car, bought a van, and started living the road life. For several years I had no home except my van, with a little dog for companionship. Along the way I got a record deal with Work Records, a part of Sony, and at long last started putting out records.

Still, every time I thought I’d put the long shadow of Dylan behind me, it would loom up and engulf me again. Every new record I made, no matter how different it seemed to be from the last, brought on new comparisons to the man from Hibbing. When I’d started out, nothing was so flattering as “You know who you sound like? Bob Dylan!!” But it became increasingly frustrating. If I had a penny for every time I heard some Dylan comparison, I’d be a millionaire.

At some point you see it coming before anyone even says anything. Eventually you make some kind of peace with such things. Mainly because you have to. Maybe you make jokes. “I sort of see Bob Dylan as the Dan Bern of the ’60s,” I said once. I wrote a song, The “Talkin Woody, Bob, Bruce and Dan Blues,” where I break into Bruce Springsteen’s compound and try to serenade him, much as the young Dylan had done for an ailing Woody Guthrie.

I found The Boss asleep in bed

Pillows piled up round his head

I turned on the light, took off my coat

Stuck a thermometer down his throat

Said “Don’t talk….you look pale, Boss….not at all well!”I said “I wrote you a song called ‘Song to Bruce’

“With a tune I stole from one of yours”

To his platinum records next I pointed,

Said “I just want to be anointed!”

He said, “I ain’t sick…this ain’t a hospital…and how’d you get past the security gate?!!”

In 2007 I got to write songs for the movie “Walk Hard,” a fake biopic about the legendary (and fictional) Dewey Cox, played by John C. Reilly. One of my assignments was to write some faux Dylan songs. My whole life I’d tried to not sound exactly like Dylan. Here I was being asked to actually channel him. I jumped all over that one:

Mailboxes drip like lampposts in the twisted birth canal of the coliseum

Dewey drawls in the first lines of “Royal Jelly,”

Rimjob fairy teapots mask the temper tantrum oh-say-can-you see ‘em

Stuffed cabbage is the darling of the Laundromat

And the sorority mascot sat with the lumberjack

Pressing, passing, spinning, half-synthetic fabrication

Of his time…

There was more. From “Farmer Glickstein:”

From every job now I’ve been fired

From Judas to Joan of Arc inspired

Red clouds on the road required

Three new garbage men just hired

My bloodshot eyes from whiskey tired

The beehive stovetop tractor moonstone sleeping….

And so on.

That was fun. It put a little distance on the whole Dylan thing for me. He was him, and I was me. Even if, whenever I saw a picture of his first album cover, I still thought it was me. But whatever. We all have our stuff.

Sometimes, I didn’t think about Dylan so much anymore. I had a beautiful daughter. I composed hundreds of little kids-sized songs with her. Put out a couple kids albums. By now I’d made about 25 records. My time in the southwest was evident in my work. Merle Haggard, George Jones—those guys had as much influence on me as Dylan, I figured. I was painting a lot (when I started painting in the late ‘90s, someone gave me a book of Dylan’s paintings. They were good. “Damn, he’s even done that!” I thought). I was writing songs for cartoons. Things were OK.

Then, one night in late September of 2015, I got a note from a friend, Paul Zollo. Paul was the guy who used to write the big interviews for “Song Talk.” He’d interviewed Dylan (for real), which had run in the same issue as my spurious interview with Dylan’s Mom. In 1991.

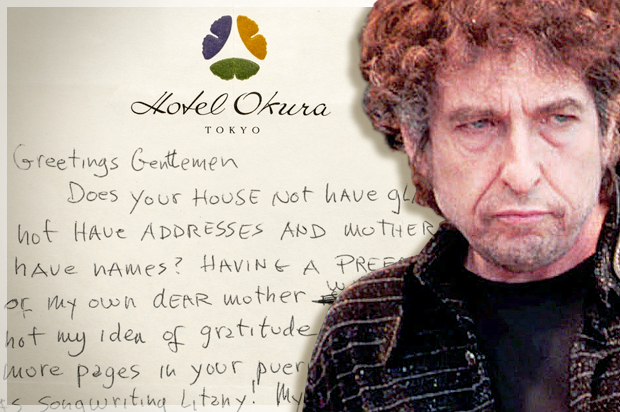

Apparently, Dylan had seen our Song Talk issue, way back in 1994. With Paul’s interview of him. And mine, of his mom. Dylan had been in a hotel in Japan. Why he had seen it three years after it ran, while in Japan no less, I have no idea.

But Dylan had been incensed. He wrote a scathing letter, on the stationery of his Japanese hotel. He called me a “Scurrilous Little Wretch with a Hard-On for Comedy.” Somehow the letter, unsent at the time, had surfaced and is being auctioned by Sotheby’s, expecting upwards of $12,000.

He had some choice words for Paul Zollo too. It seems Paul’s main sin was guilt-by-association—his piece had appeared next to mine.

At first I was speechless. After most of a lifetime of songwriting, performing, road-warrioring, recordmaking—always in the shadow of this guy, always somehow measuring myself against this guy—it seemed I had, indeed, pierced the bubble of his consciousness. And this was his judgement! “A scurrilous little wretch!”

I wanted to say, “Bob! It was a joke, Bob!” But I guess he knew that. After all, I had a “hard-on for comedy.” So, even though he knew it was a joke, he didn’t find it funny. I guess I shouldn’t have used his mom in the piece. Still, it seemed so obviously ludicrous. But still. I guess if you’re Bob Dylan, and people take potshots at you all the time, maybe your patience wears thin. Especially regarding your mom.

I couldn’t believe it. It was like God finally acknowledges your existence, and when he does, he flicks you off his shoulder, like an annoying flea.

What was I to do? Laugh it off? Maybe. But still. This was Bob Dylan!

Well, Bob. I mean, Mr. Dylan. Sir. Your Excellency. Probably you forgot all about it. It’s been over 20 years! For sure, you’ve got other things to think about! But who knows. So here’s the thing. Maybe it was lame, but it wasn’t meant to cause any harm or pain. If it did, even fleetingly, like, for a millionth of a second, I apologize.

If this is the only time our spirits will ever cross paths, well, so be it. I guess that’s life. Kind of ironic, for me. Probably less so for you.

My high school principal once grabbed me in his special death-grip and, leaning low, said, “Some day, you’re gonna get in big trouble for your mouth.”

His words have proven prophetic more than once. Still, even he probably couldn’t have imagined that Bob Dylan would call me “a scurrilous little wretch.”

On the other hand, most people never get a personal quote from Bob Dylan about anything.

That’s something. They can’t take that away from me.