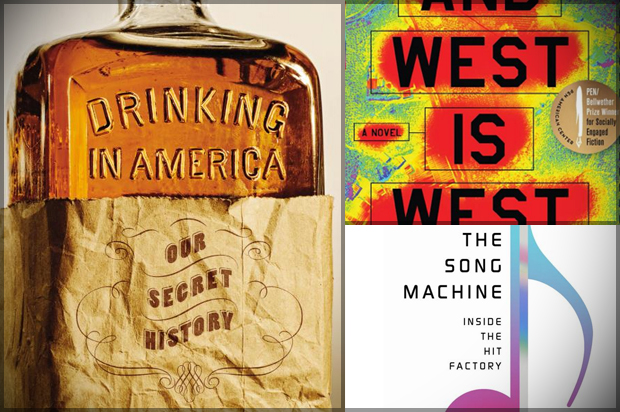

For September, I posed a series of questions — with, as always, a few verbal restrictions — to six authors with new books: Ryan Britt (“Luke Skywalker Can’t Read: And Other Geeky Truths,” Nov. 24), Susan Cheever (“Drinking in America: Our Secret History,” Oct. 13), Ron Childress (“And West Is West,” Oct. 13), Josh Gondelman (co-author with Joe Berkowitz of “You Blew It!: An Awkward Look at the Many Ways in Which You’ve Already Ruined Your Life,” out today), Maris Kreizman (“Slaughterhouse 90210,” out today) and John Seabrook (“The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory,” out now).

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

GONDELMAN: It’s basically “Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day” but nonfiction, and for grownups. Is that too much summary? If so, it’s about the feeling of remembering something embarrassing you said ten years ago and thinking about it all day.

CHILDRESS: Ethan Winter and Jessica Aldridge, a Wall Street quant and a military drone pilot, respectively. Bit players caught in a nexus of secrets, technology failures, identity loss and family crises. Also, it’s about America’s transitional state between a society managed and run by people to one controlled by algorithms and mediated through screens.

SEABROOK: It’s probably as close as I am ever going to come to satisfying my true ambition, which is to write a musical. People talk for a while, and then there’s a song.

BRITT: My book is an attempt to replicate on the page what it’s like to talk to me in real life when I’m conflating weird opinions about science fiction with random personal anecdotes.

CHEEVER: It’s about a new way of writing history using the vivid details of actual lives to show how past events unfolded. I have tried to take the pictures of our forefathers off the wall and let them dance.

KREIZMAN: “Slaughterhouse 90210” is about how books intersect with TV and film, how loving books and loving pop culture go together. They’re not mutually exclusive enjoyments, and at best they enhance each other.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

CHILDRESS: Current news. The Internet. Military blogs. Stock market flash crashes. Enhanced security. The acceptance of mass surveillance. Diminished expectations. The possibility of resistance.

BRITT: There’s a fictional character who is name-checked in the title of the book whom you maybe have heard of. Gin and tonics were probably an influence. The older brother from the band Oasis — Noel Gallagher — has probably influenced all my nonfiction. Not necessarily his music. But his interviews. I am not kidding.

SEABROOK: My parents were a major influence on this book, because they both loved the pop songs of their day (Andrews Sisters, Frank Sinatra) and played them around the house — my mother on the piano, my father on the record player. And I noticed that whenever music was playing in the house, everyone seemed happier. The furniture seemed to float a millimeter or so off the floor. I wanted to recapture that happy feeling in the book.

CHEEVER: Many of the historians we revere in this country write with a kind of sleepy gravitas, a soft-focus lens that leaves out all the interesting things — sex, food, clothes and especially drinking. I looked for the exceptions.

KREIZMAN: US Weekly, TV recaps, cartoons, fan fiction, pop music, that feeling of accomplishment and mortification after a particularly long period of binge-watching or binge-reading.

GONDELMAN: Our book is influenced enormously by Freudian slips, chemistry-free first kisses and botched job interviews.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

SEABROOK: The Boy calls shotgun, reprograms the radio presets to pop stations, Kesha’s barbaric yawp enters my life, WTF IS this shit? “You spin my head right round” … Thumpa thooka whompa whomp Pish pish pish Thumpa wompah wompah pah pah Maaakaka thomp peep bap boony Gunga gunga gung

GONDELMAN: The opposite of what was happening in the book. An emotional Benjamin Buttoning, if you will.

CHEEVER: Same old, same old.

BRITT: Travel. What-am-I-doing-with-my-life-is-this-really-where-I-want-to-be. Also: New York nonsense.

KREIZMAN: Abject self-doubt; attempting to watch and read everything all at once in big deep gulps and wishing I could pour books directly into my brain; working on my night cheese.

CHILDRESS: This and that. Reading. Travel. Exercise. Netflix. Art openings. Housekeeping. Database projects. Motorcycle rides. Audiobooks.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

CHEEVER: The words that hurt are often code words for the writer being feminine. Paul Muldoon called me “soppy … sloppy and sentimental,” after my last book, a biography of E.E. Cummings. Would he have said that about a man? There are many examples of this.

KREIZMAN: “Wake up, sheeple.”

CHILDRESS: I’m concerned that my work may be pigeonholed in the thriller category because of the pacing … but I do like a story that keeps moving.

BRITT: My book comes out in November, so I’m in that stage where everyone is giving me tons of thumbs-up and winks and smiles. I will say this: despite the word “geeky” being in the subtitle, I try to be very careful about how I use that word.

GONDELMAN: I’ve tried not to read reviews, but sometimes things come across my social media feed. My least favorite is any synonym for funny that’s not “funny”: Knee-slapping, rib-tickling, anything about the reader’s “funny bone.” So often, when people talk about comedy, they revert to the language people used to review the Marx Brothers. I imagine “garbage,” “seizure-inducing,” and “nauseous” would sting too.

SEABROOK: “Brilliant.” Such a cliche. “Deeply felt.” Gag me with a spoon. “Best thing I’ve ever read.” Bullshit!

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

GONDELMAN: In a dream world, I would love to be a master pastry chef, because it combines something I love doing (baking) with something I’m not good at doing (baking). BUT! Practically, if I weren’t writing and doing comedy things, I’d like to teach kids to read. I would be good at that in real life.

CHEEVER: I don’t really think of writing as a career. It’s something that happened to me. By working harder than I knew it was possible to work, I have become passable at it.

CHILDRESS: Computer programmer. As a coder, like a writer, you sit in a room and type, solving small problems as they arise while developing a more comprehensive overall goal that is similar to a narrative.

SEABROOK: My high school aptitude test said I would make a good hospital administrator. There are a lot of sick people out there who should be very glad I didn’t follow that suggestion.

BRITT: I wish I’d become a paleontologist, because I love dinosaurs. But I think I realized at a young age that those folks are outside a lot and I really can’t handle getting sunburned.

KREIZMAN: I would be The Rock’s dog walker.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

KREIZMAN: I am pretty great at juxtaposition, less great at subtle yet effective self-promotion (self-promo is one of the foremost elements of craft, right?).

BRITT: I’m decent with weird and quirky analogies. I’m bad at patience. I like jumping to conclusions without explaining myself and praying that my weird analogy will confuse you long enough to get on-board my crazy space-train.

CHEEVER: All writers have strengths and weaknesses. I am terrified of being boring, so I write short, compressed stories that sometimes don’t give a reader time to think about what they have read. I struggle to slow down.

SEABROOK: I’m pretty good at the Shaker chair-building part of it. Simple woodworking that you can sit on and not hurt your butt or worry about the back giving way. I’m terrible at imagining things that didn’t happen — which is why I stopped writing fiction at the age of 23.

CHILDRESS: I’m good at editing myself down. I dislike using too many words and am suspicious of clever phrases that can seduce. This may not always be a good thing. I wish that I wrote faster, probably so that I could cut more.

GONDELMAN: I tend to be better at describing feelings and ideas, and worse at painting a picture of any physical thing. I have terrible spatial reasoning skills so even if I were describing my girlfriend, whom I see every day, it sound like I was talking about a child’s drawing of her. “Very beautiful. Glasses. Brown hair. Super smart brain. Bigger than our dog. Smaller than me.”

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

BRITT: I just think about singer-songwriters, or actors who write their own scripts, and I figure, well, it could be worse!

CHILDRESS: I don’t think about anyone reading what I’m writing when I’m writing. I’m enjoying the writing process — the exploration of ideas, the solving of compositional problems — as an end in itself. I hope that’s not hubris.

SEABROOK: With large dollops of bitter experience. I started out assuming people would automatically be interested in things that interested me, only to be shocked — shocked! — to discover they were often not. So with “The Song Machine” I set out to write about the most popular cultural artifacts in the world — pop songs. Not sure if people who like pop songs read, or if people who read like pop songs. I guess we’re about to find out. And hey, the audio book is amazing!

GONDELMAN: It makes me happy to smash words together. So it’s nice when I can be met with warmth and enthusiasm, but doing standup comedy has taught me how to push through the fact that statistically speaking, 100% of Earth’s population population doesn’t have any interest in what I’m doing at all. I try to think less about having/deserving an audience and focus on enjoying the privilege of creating things I like.

CHEEVER: It’s certainly hubris, but it’s the same hubris that makes me a teacher, a useful friend, a good mother for that matter. I hope that when readers look up from the last page of my book they will see the world in a new way. It would be hubris to think that happens automatically; I think it’s humility to hope that it might someday.

KREIZMAN: I look at Twitter and how everyone I know is constantly spouting opinions about anything and everything and I think, Why not me?