The story of Cleopatra has been told many times over, in many different ways, though there’s a certain consistency to the tale’s key elements — the seductiveness, the asp, the sultry kohl eyeliner. In her new novel, “Cleopatra’s Shadows,” Emily Holleman decided to break free of the clichés dogging the last great pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt, the better to see her fresh. The book is the first in a planned series of four that will tell of Cleopatra’s rise and famous fall, but Cleopatra herself hardly appears in it; we glimpse her, in the opening pages, not as some Elizabeth Taylor-esque glamazon sure of her erotic power, but as an 11-year-old girl, setting sail from Alexandria with her father, Ptolemy Auletes, to seek support from Rome against her half-sister, Berenice, who has taken the throne for herself.

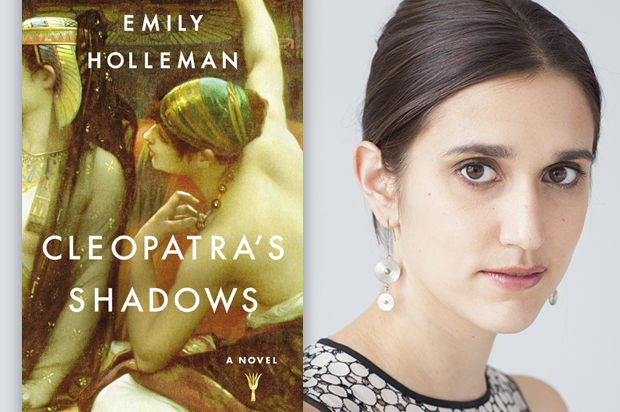

Berenice, 19 and in charge of holding together an unstable kingdom, is one of the shadows of the title. The other is Arsinoe, Cleopatra’s younger sister, left behind in Alexandria to fend for herself in an environment of political and familial treachery. The book’s title turns out to be slyly deceptive; Arsinoe and Berenice might be confined to the shadows of history, but here they are squarely in the limelight, powerful protagonists of their own dramas. They could easily give the women of “Game of Thrones” a run for their money. I first met Holleman when we were about as old as Cleopatra is as she leaves for Rome; recently, I sat down with her at a coffee shop in our shared Brooklyn neighborhood to talk about heroines and Hellenistic Egypt.

Tell me how you got interested in this: Were you interested in trying to find a different way of approaching Cleopatra or did you start at a point of interest with her sisters?

I started at a point of interest with her sisters. I was reading Stacey Schiff’s book about Cleopatra right before going to Egypt with my family. Toward the beginning, there’s this mention of Arsinoe, and Stacey Schiff describes her literally in a footnote, something like, “Very little is known about Arsinoe’s motivations but that hasn’t stopped even the most illustrious historians from trying to figure them out,” and then quotes something from [a] French guy who’s like, “If Arsinoe hadn’t been jealous of Cleopatra, she wouldn’t have been a woman, let alone a Ptolemy.” [A] very pre-World War II French historian thing to say about her motives.

That really caught my eye: this idea that all women must be by default jealous of any sort of sexual successes [of their peers]. He, of course, was talking about Cleopatra’s relationship with Caesar, which is much later than what we cover in this book. That was what really intrigued me: the idea of taking this woman whom we see always from the perspective of her lovers, from the perspective of Rome, and flipping that on its head and looking at it through the eyes of her sisters whom we now have completely forgotten in popular culture.

From the point of view of historical fiction, it seems to me that it’s kind of a dream because you have one subject so many people have focused on in so many different ways — in history, in fiction, movies, a true icon — and then you have these shadows surrounding her whose names we know but we have no sense of what their lives were like in any of their particulars.

It is kind of ideal. I think the best historical fiction is that stuff that you’re like, “Oh, this sheds light on something that we can’t really explore through history in a meaningful way …” There’s not enough [in the historical record] to write a history book about Arsinoe, or really about Berenice.

In your book, you have almost a dueling banjo situation between Arsinoe and Berenice, which is so interesting because they come from such opposed points of view and motivations when the book begins with their father, Ptolemy the Piper, fleeing to Rome and Berenice seizing power and the youngest, Arsinoe, waking up to find that she has been abandoned to her fate and to the mercy of her older sister. So Berenice in particular begins from a really unsympathetic point of view. She seems cold and dominating and at least I — when I began — sympathized very much with the scared little girl. And yet you give Berenice equal time and equal perspective.

I can’t remember when I first decided I was going to write from two perspectives, because the idea behind this book — which is going to be the first in a planned set of four — was to tell Arsinoe’s story. From almost the very beginning, I started writing from Berenice’s perspective, and at first it was as a foil in a lot of ways, right? I have this child’s perspective who doesn’t know what’s going on, who’s very much disenfranchised in every meaning of that word — she has no knowledge, she has no power, she has nothing.

But then the more I wrote from Berenice’s perspective, the more I became fascinated with where she was coming from, what brought her to this point, because obviously Berenice starts, not at her pinnacle, but at the beginning of her own rise. The more I was exploring that, the more I decided that this was another almost Greek tragic story to tell, and one of the struggle for power and what it means to have power. I think a lot of the conversation is both of these women — well, a woman and a girl — figuring out how they can operate in a system that is in many ways weighted against them, no matter how high or low they are in any particular moment.

One thing that is so interesting to me in the book is the way that each of these characters — the girl and the woman — have to surround themselves with advisers and have to make the best sense that they can of the advice that they’re given. Berenice has her circle of advisers. She and Arsinoe have their own eunuchs, which I love as a relationship: eunuch pairing with a young woman, meant as this sort of guide through the world and through knowledge. But, as we see with Berenice, the relationship can become quite twisted when she has to trust him for political advice despite having her own ideas about how to operate.

It’s not just with young women although obviously that’s where it comes in here. Ptolemy the brother, who comes in as a character in the next book, also has a eunuch. It was probably especially important for young women because it’s a non-threatening — scare quotes non-threatening — male figure, or pseudo-male figure. And the other thing is that for these eunuchs, this is the only way to power. They have so much invested in their mentees, right? They can’t have their own families.

They’ll never be able to marry into the throne.

They’ll never be able to marry into the throne. They can’t marry into any kind of aristocracy. On some level there’s a paternal relationship but also one where there’s this constant fear of being displaced, either by a husband, or by a new adviser, or by a child or by all these other “natural” family ties. For the eunuchs, it’s best when [the mentees are] kids and as soon as they stop needing them or relying on them as much — that’s their whole livelihood, that’s their whole life.

Berenice in particular is at this interesting juncture between her childhood and her adulthood. And the eunuch plays an interesting role in that because we see in flashback how much she once relied on him, how he was the source of support when her father left her mother for his concubine, the mother of Cleopatra and Arsinoe and their younger brothers. You give us the sense of how she’s always had to rely on this eunuch, this other person to carry her through and advise her and support her in her own path to power.

I’m not saying that the Ptolemy kings and queens did not have any relationship with their children, they definitely did — King Ptolemy the XII obviously seemed to have had a much closer relationship with Cleopatra than he did with his other children.

Which you paint as a favoritism relationship. That he was kind of swept up. When she was born, he cast aside Berenice, his older child.

Certainly, he had a favoritism relationship with [Cleopatra]. The fact that there is evidence that he took her and her alone and not either of his sons who, granted, were quite young at the time, with him when he fled to Rome.

That is fascinating to me, because — as you do stress in the book and as all of us who have become accustomed to thinking of ancient times know — the boys are the more powerful. Berenice as a female ruler has to make some sense of that and think of the risk that her younger brothers might pose. But it is true that Ptolemy takes Cleopatra with him and Cleopatra, of course, rises up to become this famous last of her line.

The Ptolemies are a very interesting set in terms of the relationship between men and women and power. Berenice ruled by herself, largely, for two and a half years. [And] there is sort of this history [among the Ptolemies]. It’s not common for women to rule alone, but it’s common for them to have, if not equal, nearly equal partnerships with their brother-husbands. So while boys were favored and certainly had more default power, there was some history of women ruling almost on their own or de facto on their own.

There’s a great scene where Berenice remembers seeing the tomb of Hatshepsut and seeing the queen shown with beard. She remembers going with her father and asking where’s the queen, and he says that’s the queen. And she realizes to rule, your queen has to be a king.

Right. Hatshepsut of course was one of the pharaohs of the New Kingdom. There is no [word] for queen in the Egyptian language, in the native language, so Hatshepsut really turned herself into a man in her official portraiture. And there’s certainly evidence that Cleopatra took on certain roles that would traditionally be played by Horus — Horus being a male deity — when she went to do various activities along the Nile to placate the local cults.

You give such a vivid sense of all these different political concerns and religious concerns that the rulers had to incorporate for strategy. In this book, it comes across really clearly that these monarchs really are the rulers of these two kingdoms. You have the Ptolemies who are of Greek lineage, who don’t speak the local language, who have this 300-year history of rule. At one point, you have Berenice going to placate the people of Upper Egypt because the Nile has not flooded and the grain has not come. And she is not quite revolted but certainly put off by some of the coarseness of the local culture and the local deity cults.

The Ptolemies certainly would have considered themselves to be the inheritors of Alexander the Great. And the local cults are not Berenice’s favorite aspect of her rule, for sure. It’s a very foreign, it’s a very weird thing [for her]. She goes down there and there is definitely a separation [from Alexandria] … There’s almost an imperialistic vibe to it, if you’re thinking in terms of people who’ve ruled another culture for years and years the way in India you had first the Mughals and then the British, both accepting — well, the British not so much, but the Mughals — a lot of native culture, but also keeping themselves very separate. [And the ancient Greeks] certainly thought of everybody else as being lesser than they were. Even though the Egyptians had a much longer culture and lineage than anybody else at the time, which the Greeks half-recognized, but still saw anyone who didn’t speak Greek as essentially barbarian. So that’s an interesting dynamic we have for Berenice going into this.

And for Arsinoe, “Antigone” seems to be her favorite book. In the beginning, she starts out really sympathizing with Ismene. She loves her older sister, Cleopatra, she thinks of her as brave and fearless and misses her deeply, and thinks of herself as Ismene in deciding whether or not she will be able to be as bold as her older sister is. And you see shifting sympathies as the book goes on, especially as she has this other model of sister and leader before her in Berenice, you see her shifting into if not exactly Antigone position, the position of the more active sister, her own heroine.

A lot of what drew me to this book is my own experience — my own experience ruling a dynasty! [Laughs.] No, my own experience as a younger sister, and as somebody growing out of that almost worshipful idolization of the older child, because they are in so many ways — especially when you are quite little — so much better at everything than you are.

And you are the youngest of two sisters?

I have one sister who’s three years older than me, and I have a half-brother and a half-sister who are 12 and 14 years older than I am.

So similar in position to Arsinoe.

Yes, exactly. It’s all autobiographical is what I want people to hear, which is going to get really fun in the later books when people start killing each other. [Laughs.] I am definitely very much in the youngest child position. But I think what was interesting about this was also looking at the older sibling perspective and seeing that that has its own challenges when I’m of course so familiar with what feels difficult about being the youngest.

Tell me a little about what you read. I’m assuming you had to read history of all kinds, contemporary and ancient, so I’m curious about that, and also other examples of historical fiction or other fiction or nonfiction, whatever you read to inform you.

In terms of contemporary authors I found Adrian Goldsworthy — both “Antony and Cleopatra” and his book “Caesar,” which I’ve been sort of going over again as I work on the second book — super helpful. But where I really began, after getting a general [historical] overview, was going back to the ancient sources, and reading Cassius Dio and Appian, and of course Plutarch, who’s sort of the most fun of the ancient sources, although Suetonius is fun too. He’s very salacious. [Whenever there’s a] story about Caesar’s lovers or Caesar’s potentially having a romantic homosexual affair with a king from what they [then] called Asia — he doubles down on every one of those. I [also] read a lot of Sophocles, a lot of Euripides, a lot of Aeschylus. And I went back a lot to Homer, to just get that in my head, especially for Arsinoe. When you’re a kid these stories that you’re told over and over again do so much to shape the way you see the world and the way you think about the world. And in a culture where people really were expected to memorize large swaths of things like “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey,” I feel like that’s got to echo through your mind.

You have a line where Arsinoe’s eunuch says, in the context of their lessons, that any child has read “The Odyssey.” And for us, we’re like, “really, what?” But it makes total sense. These are the stories you grow up with. These are your archetypes.

A lot of what I was thinking about with Arsinoe and the children of the court was really how much their world was shaped by these stories, just like our world is shaped by a much wider selection of stories. It’s not just biblical stories or mythology or stories like “Peter Rabbit” or these classic kids books like “Alice in Wonderland,” [it’s] also the things you watch on television and the things you see on YouTube — it’s a very wide swath. But [back] then, especially for these royal kids, there were these like stalwart, pinnacle of their [Hellenistic] ancestry that were sort of hammered into them, which is obviously different than now.

What about contemporary historical fiction? Did you read anything to inspire you about approaching a defined subject through your own imagination?

I don’t think I specifically read anything for that purpose when I was writing, in part because there’s always the fear of sort of slipping into somebody else’s voice. But in terms of, historically, things that I’ve read, certainly “The Red Tent,” [which takes] a known subject, a biblical subject in this case and switch[es] that on its head. Another one — this is not truly historical — would be “The Mists of Avalon,” which takes the Arthurian legends and brings it to the female perspective, which I found super fascinating. And then more recently, “Song of Achilles” is something that I loved, which takes Patroclus and sort of retells “The Iliad” but also retells a lot of other things from [his] perspective.

You use dream as a frame device of kinds. Arsinoe has dreams that are portents. The book begins with a violent dream that she has when she wakes up to discover — she wakes up to run down to the docks to see her father and Cleopatra’s ship sailing away. And dreams guide her and also frighten her throughout the book. Tell me about your use of dreams.

One thing that I found when I was reading the histories was everyone from Appian to [Cassius] Dio will be relating history, history, history, history and then Caesar had this dream, or and then so-and-so had this dream. Whether or not [the visions] were real or whether or not they really are portents, there is an enormous amount of weight put on dreams and divinations [in antiquity] to the point where they’re reported in the histories. The big thing is the question of how people perceive their realities and the different weight we put on different aspect of realities. And in the ancient world, there were certainly a lot of people who thought dreams really had this meaning that we don’t ascribe to them anymore.

It’s also a frightening power. It’s frightening for Arsinoe in the book, because she has intimations as things happen in her actual life that her dreams are coming true, she sees the symbols of her dreams acted out in real life, and also for her eunuch. At first, he seems skeptical of her dreams, but it actually seems he fears the power of her dreams. Having this gift is a curse as well.

Exactly. And it is in so much of the Greek literature, it is a curse. The most famous being Cassandra who is cursed with these portents and seeing all these thing that are going to come to her family and the fall of Troy and no one listening to her. It’s the whole fate versus free will idea. If you know what will happen but you can’t do anything to stop it, is that a gift or is that a curse?

Similar to the position that you’re in, where you know what will happen but can’t do anything to stop it.

Exactly, which is horrible. I can’t be like, “OK, and then Arsinoe rules for 300 years.”

Now you’re heading in the next books into known territory. You’re going to have to take on Caesar and Mark Antony and Cleopatra herself. How is that going to be different for you than basically beginning with these two blank slates of her sisters?

I’ve had a draft [of the second book] for a long time, which I keep revising and rewriting, and it is very different. There’s so much more known in terms of what happens historically, and there’s a lot more pressure in terms of writing Cleopatra. I’m just getting up to my edits in the Caesar passages. You’re making these choices that feel — they feel very big. But in a good way. It’s a less open experience than with “Cleopatra’s Shadows,” where it’s almost like “anything goes.” These people [Arsinoe and Berenice] — nobody knows much.

That might have been a good last question. But do you find your allegiances shifting?

Gosh, yes. Always, very often. Writing this first book, I feel like I started out really team Arsinoe.

As does the reader.

And I sort of end up — I mean, I love Arsinoe — but I ended much more team Berenice than when I first started writing. And I feel like in each book it is this exploration on some level of the sort of default protagonist who’s Arsinoe and the default pseudo-antagonist and exploring that character. And that becomes really fascinating. The more I write from one perspective, the more I feel like, “No, this is the person who I want to come out on top.”

Of course, it’s history and everybody dies in the end, which is the default truth about writing about people who lived 2,000 years ago. They’re all dead now.