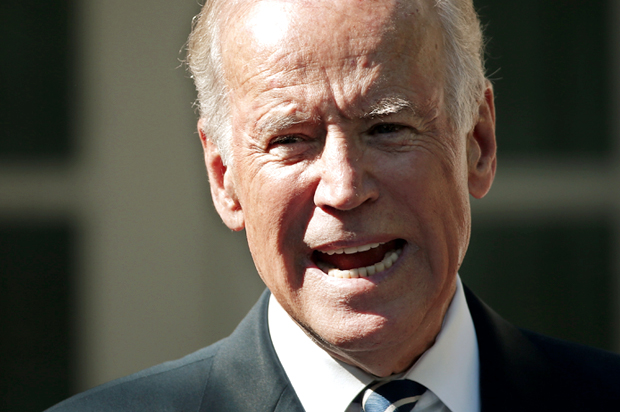

As you quite likely know by now, Vice President Joe Biden announced on Wednesday that he would not run for president. The news is being greeted with disappointment by a press corps that’s looking for any excuse to inject some drama into the relatively dull Democratic primary. But as I’ve argued previously, I think that Biden’s foregoing a campaign will ultimately be for the best — for him and the Democratic Party, both.

That said, Biden’s speech announcing his decision not to run — which was effectively his farewell speech, though he promised not to be “silent” for his remaining time in office — was a fine note to go out on. Alongside at least seeming heartfelt (I agree with Michael Tomasky: authenticity is bullshit), the speech was hopeful, even romantic. One section near the end was particularly striking for its can-do confidence. After touching briefly on income inequality, political polarization, immigration reform, LGBT rights and gender equality, Biden said:

[A]t their core, every one of these things is about the same thing — it’s about equality, it’s about fairness, it’s about respect. As my dad used to say, it’s about affording every single person dignity. It’s not complicated. Every single one of these issues is about dignity and the ugly forces of hate and division. They won’t let up, but they do not represent the American people. They do not represent the heart of this country. They represent a small fraction of the political elite; and the next president is going to have to take [them] on.

Biden’s words weren’t exactly Churchillian in their grandeur or Lincolnian in their eloquence; but the sentiment he expressed — the firm belief that the American people are not as divided as they seem; that some of the most vexing and bitter policy disputes troubling the country are, “at their core,” deceptively simple — is beautiful. Unfortunately, it’s also not true. And if they’re to continue building on the foundation Obama and Biden set, the next Democratic president needs to know this.

For one thing, while it’s undoubtedly true that most Americans don’t disagree with one another as vehemently and viciously as partisan media would lead you to think, to say that “the forces of hate and division … do not represent the American people” not only begs the question (what serious person would describe themselves as supporting “hate and division”?) but also misleads. It suggests that America’s problems stem from a small conspiracy of unknown elites — an idea with a not-so-great track-record in politics — and it erases what are genuine and often irresolvable differences.

Remember now, the goal of a society defined by liberal democracy and pluralism is for everyone to get along with each other, relatively speaking. And having everyone get along with one another is not the same thing as having everyone agree. Humans have been doing this whole civilization thing for a while now; and for the vast majority of that time, we tended to settle our differences by killing one another. Liberal democracies don’t work that way (usually) — and that’s why they’re valuable, not because they bring everyone together.

With its “Kumbaya” overtones, this was probably the section of Biden’s speech that most reminded listeners of President Obama, who stood by Biden’s side throughout the veep’s address. But although both liberals and conservatives have mostly endorsed a narrative in which Obama promises to be a grand uniter in 2008 before acquiescing to reality (or his true nature, as Republicans might say) in 2012, that’s an oversimplification. And it’s one that gives Obama too little credit.

Obama never denied that there are profound differences between millions of Americans. His analysis was never that naive. What Obama argued, instead, was that these differences — which are real, significant, and sometimes unresolvable — did not preclude cooperation on other matters. In this regard, comparing Biden’s farewell speech with a Daily Kos “diary” that then-Sen. Obama wrote in 2005 is revelatory. Because rather than offer some version of Biden’s “it’s not complicated” mantra, Obama writes:

[T]he truth of the matter is this: Most of the issues this country faces are hard. They require tough choices, and they require sacrifice. The Bush Administration and the Republican Congress may have made the problems worse, but they won’t go away after President Bush is gone … The bottom line is that our job is harder than the conservatives’ job … And I firmly believe that whenever we exaggerate or demonize, or oversimplify or overstate our case, we lose … Whenever we dumb down the political debate, we lose.

That “diary” was most immediately a response to a debate among Democrats (one that, from today’s vantage, seems almost quaint). But while Obama’s rhetoric has changed in the past 10 years, there’s nothing in his record as president to suggest that he no longer believes that politics — and especially progressive politics — is, well, hard. It is complicated; Americans do disagree. Not always, but often. And not just about secondary or tertiary issues, either.

If the Democratic Party holds the White House in 2016, it’s quite likely that the next president will face Republican majorities in both chambers of Congress (almost certainly in the House, at the very least). If that president hopes to do more than maintain the defensive position that, out of necessity, Obama’s adopted since 2011, they’re going to need to have a clear understanding of not only Congress, but the opposition, too.

That Vice President Biden doesn’t seem to get this hardly makes him a bad progressive, much less a bad person. But it is a reminder of why, ultimately, it’s a good thing he’s not running for president.