A few months before my father turned 85, I received one of his rare emails. "All I want for my birthday is to be with all of my kids — I may not be around much longer," he wrote. "Figure out a date when we can meet in San Diego this summer."

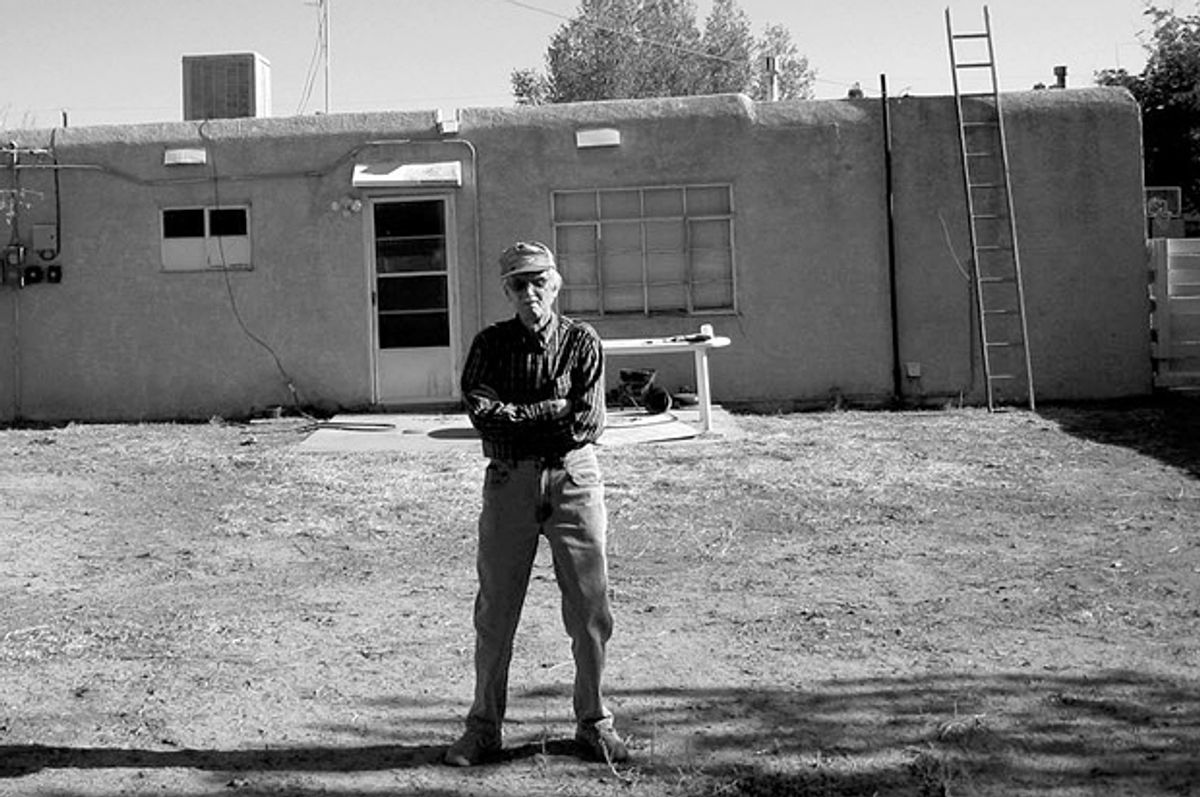

San Diego was the last place we'd all lived under the same roof. Dad's alcoholism, depression and violent outbursts drove my mother to divorce him when I was in high school. At the time, I wondered what had taken her so long. After my parents split, my father quit drinking and moved out of state, eventually settling in Alamogordo, New Mexico, where he lived alone.

I saw him once every three or four years, if that. I didn't see my brothers and sister often, either — we were not an especially close-knit bunch. Our only other attempt at a reunion in Sedona — a spot Dad chose because he could drive there — had not gone well. The 8-hour haul and the heat sapped his energy. My brother Peter didn't show up. And the desert sun brought simmering resentments between me and my other brother, Richard, to a boil. By the end of the weekend, we weren't speaking.

I was done with reunions.

Yet there was something about Dad's latest request that gave me pause. My father had been threatening to die for a least a decade, but now his claims seemed more believable. Six months earlier, he'd had surgery for an aortic aneurism. Though he'd returned to the weekly senior center dances he loved, and had recently won first place in Alamogordo's annual Senior Citizen Talent Show playing his beloved ukulele, he was still anemic and weak. In typical fashion, he blamed his slow recovery on shoddy doctors. But I couldn't help thinking maybe age and all that hard living were finally catching up with him.

Reluctantly, I decided I owed it to Dad to take another shot at organizing a reunion. I was the eldest, after all, and it seemed to me I had a responsibility, if not to him then to myself and my siblings, to at least try to fulfill his wish.

I contacted my brothers and sister and made a plan to meet in San Diego for Father's Day weekend. It had been 20 years since we'd all been together with him.

Dad hated flying. But he endured two flights, plus a long drive, to get to San Diego. When I picked him up at the airport, his ukulele was out of its black leather case the second his seatbelt was fastened. He was strumming and singing "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" before we reached the exit.

That evening, we all met for dinner at a casual Mexican restaurant. Dad complained it was too fancy — he preferred Wendy's. He scowled at the cucumbers in his salad, saying they gave him heartburn, and angrily flicked them to the side of the plate with his fork. I bickered with my siblings about plans for the next day. The tension stirred up over our tacos and burritos lingered as we walked back to our motel.

Sadie, my 10-year-old, skipped ahead of the group to hide. A few minutes later, she jumped out from behind a wall, planting her feet in the middle of the sidewalk.

"Boo!" she screamed.

"Do that again, and I'll shoot you," Dad snarled. "I've got a gun."

"Jesus, Dad!" I snapped.

Sadie cowered behind me. I didn't know if I could survive a night with my father, let alone a whole weekend. The way he lashed out at Sadie yanked me back to my childhood when similar verbal attacks — usually aimed at my mom after he'd been drinking -- were as familiar as the sickly-sweet stench of the pipe he smoked. I'd hide in my bed, covers pulled tight over my head, trying to block out his voice and praying he wouldn't lurch down the hall and open my door. A father was supposed to make you feel safe. In those moments, mine made me sick with fear and shame. I wished that he would leave forever — then maybe I could fix our broken family.

Back at the motel, Dad's mood lifted once he got his hands on his uke. Peter picked up his guitar. While the seals at the beach across the street barked in the background, the two of them treated us to a concert of Elvis, Johnny Cash and Gordon Lightfoot. This was the softer father who'd also been part of my childhood, the one whose music lulled me to sleep when I was Sadie's age, and who patiently helped me with the algebra I never mastered.

Later that evening, he offered to give Sadie a lesson on the ukulele. They sat side by side on the sofa, Dad gently placing her fingers on the strings and teaching her the words to the little song he used to tune the uke,"My Dog Has Fleas." They passed the instrument back and forth, plucking and singing.

When it was time to say goodnight, he pulled me to his bony chest and whispered that he was sorry for losing his temper. He never apologized for his behavior when I was a kid. But he had gotten better at it since getting sober.

The following morning, Dad tagged along with the rest of us when we went to the beach to surf. A stiff breeze ruffled the ocean. Richard helped Sadie ride foamy wavelets in the shallow water. My sister Betsy and I paddled further out to chase bigger waves.

An hour flew by before I thought about my father back on the beach. Glancing over my shoulder, I scanned the shore for him, worried that he'd be getting cold — or bored and cranky. Clad in baggy khakis, a tan driving cap and industrial-strength orthopedic shoes, he paced back and forth along the sand. He looked so small and frail, like a stray gull's feather that would blow away in a gust of wind.

I got out of the water a few minutes later, lugging my board to the spot where Dad had settled on a towel next to Sadie, who shivered in the cold air. He wrapped an arm around her trembling shoulders, then squinted up at me.

"You okay, Dad?" I asked.

"Okay?" he repeated. "Watching all of you play in the ocean together — this is the best gift I could ask for. Today I feel like a father."

When I dropped him off at the airport the following afternoon, he hugged me tight.

"We should do this again next summer, hon," he said. To my surprise, I didn't hate the idea. I was touched by his determination to make up for lost time with his family. The weekend had gone better than I'd ever imagined. Two years later, we all returned to San Diego. Even my mother came. Dad had reached out to her after our last reunion to make amends. By the following November, they'd both put aside enough of the past to have Thanksgiving dinner together.

That first night in San Diego, my father leaned across the table in the pizza place where we were eating and fixed his gaze on me. I braced myself, seeing the hint of a sly smile forming at the corners of his mouth and a glint in his green, cat-like eyes that meant he was about to deliver one of his zingers.

"I'm getting 'Do Not Resuscitate' tattooed right here," he said, dragging a finger across his forehead. He'd already told me that he never wanted surgery again, or excessive treatment, to prolong his life if he had a medical emergency.

On the second evening of the reunion, we gathered for a barbecue at the cottage my sister had rented. Dad looked tired when he arrived with Peter, carefully lifting each foot as he picked his way across the lawn, his ukulele tucked under one arm. But he perked up when the food was ready. Always struggling to eat enough when he was alone, he swore his appetite was better when he was with his kids. He devoured fresh sea bass and baked beans. He debated politics with my husband, Jim. And he ranted about "medi-crap" and the quacks it forced him to deal with. He was reaching for another piece of fish when he suddenly doubled over.

Peter and I rode with him in the ambulance. By the time the paramedics rolled my father into the ER, he was barely conscious. The young doctor who examined him said it was serious, most likely a ruptured aneurism in his stomach. He advised just keeping Dad comfortable. I pictured my father pointing to his forehead the night before and knew he'd approve.

Everyone else arrived 15 minutes later. We formed a protective circle around Dad, smoothing his hair, stroking his face and hands. We told him we loved him. He died a half hour later. Much of that night is a blur. But I remember Richard, who I'd fought with so bitterly in Sedona three years earlier, telling me he loved me. I told him the same. And before we left the hospital, I told Peter and Betsy I loved them, too. It was the first time any of us had said those words to each other. Part of what Richard and I had argued over in Sedona was who had it tougher as a kid growing up in our often chaotic and hurtful family. Who got more or less of the love and attention we all yearned for from our father? Who suffered more when he drank and raged? But over the course of our reunions, all of that stopped mattering. What did matter -- and what we all agreed on -- was being with our father now, a man who, however awkwardly he might show it, loved us and was doing his best to make amends for the past. What mattered was not determining who had been loved most, but acknowledging our love for each other.

The next morning, we all met for breakfast at Dad's favorite coffee shop, just as we'd planned to do with him. Then we went to the beach. It was late afternoon when we returned to the cottage. Dad's ukulele case sat on the coffee table where he'd left it. Realizing I'd never again hear him sing in his slightly nasal voice, or marvel at the way his fingers worked that uke, hit me harder than watching him die.

I was in the kitchen when a familiar twang drifted through the open front door. I followed the sound to the front yard. Fog had crept in, cooling the afternoon and turning the sky gray. Sadie nestled in a striped hammock set up on the grass, the ukulele cradled in her arms. Over and over, she plucked the same four notes she'd learned from Dad. I could hear him singing the little ditty he'd taught her: My dog has fleas. My dog has fleas.

Shares