Ninety-nine years ago — on October 25, 1916 — Margaret Sanger was arrested for operating a birth control clinic in Brooklyn, New York. She had opened the clinic – the nation’s first – nine days earlier and had already served 448 clients. She was convicted and sentenced to a month in jail.

Sanger, the pioneering advocate for women’s rights and founder of Planned Parenthood, is back in the news, 49 years after her death in 1966.

The renewed interest in Sanger is due to the escalation of attacks on Planned Parenthood by Republicans and anti-abortion activists.

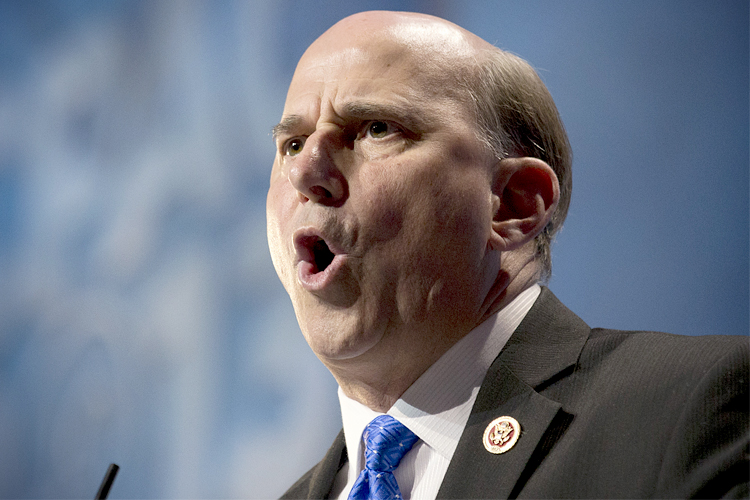

Last week, for example, GOP presidential candidate Senator Ted Cruz of Texas and his fellow Texan, Congressman Louie Gohmert, led a group of 25 Republican lawmakers who sent a letter to the director of the National Portrait Gallery urging the removal of a bust of Sanger from the gallery’s “Struggle for Justice” exhibit.

“There is no ambiguity in what Margaret Sanger’s bust represents: hatred, racism and the destruction of unborn life,” wrote Cruz. “So many of the people who have arisen out of poverty and done great things for the country and the world, if she had her way, they would have never been born,” said Gohmert.

Ben Carson, another GOP candidate for president, told Fox News in August: “I know who Margaret Sanger is, and I know that she believed in eugenics, and that she was not particularly enamored with black people. And one of the reasons that you find most of their clinics in black neighborhoods is so that you can find way to control that population.” In a speech last month in New Hampshire, Carson said that Sanger, “believed that people like me should be eliminated or kept under control. So, I’m not real fond of her to be honest or anything that she established.” At a press conference later, he specified what he meant by “people like me.” He said he was “talking about the black race.”

Back in March, New Hampshire Rep. William O’Brien claimed Sanger was an “an active participant in the Ku Klux Klan.”

The attacks on Sanger are part of the GOP’s campaign to demonize Planned Parenthood. Speaking to the ultra-conservative Values Voter Summit last month, Cruz said that in his first day in office, if elected president, he would “instruct the Department of Justice to open an investigation into Planned Parenthood — and to prosecute any and all criminal conduct by that organization.“

Jeb Bush recently claimed that Planned Parenthood should not receive federal funding because ”they’re not actually doing women’s health issues.”

Congressional Republicans have called for the federal government to pull all funding for Planned Parenthood. Last month, the House voted 241-187 to block Planned Parenthood’s federal funds for a year. The GOP-led House has opened four investigations into the organization. Earlier this month, Republicans on the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform hectored Cecile Richards, president of Planned Parenthood, for almost five hours.

The campaign against Planned Parenthood has gone beyond mere rhetoric and political grandstanding. Its clinics have been the victim of a string of recent arson attacks. In August, a security guard’s vehicle was set ablaze on the construction site for a new Planned Parenthood clinic in New Orleans. Fire investigators determined that a September fire that severely damaged a Planned Parenthood clinic in Washington State was arson. Last month, another fire was intentionally set at a Planned Parenthood clinic in Los Angeles.

None of this would have surprised Sanger. In her time, she was a controversial figure. She often ran afoul of the law in her quest to promote women’s health and birth control.

She was born Margaret Higgins in 1879, the sixth of eleven children in a working-class family in Corning, New York. Her father, Michael Higgins, a stonemason, was a freethinking atheist who gave Margaret books about strong women and encouraged her idealism. Her mother, Ann, was a devout Catholic and the strong and loving mainstay of the family. When she died from tuberculosis at age fifty, young Margaret had to take care of the family. She always believed that her mother’s many pregnancies had contributed to her early death.

Sanger longed to be a physician, but she was unable to pay for medical school. She enrolled in nursing school in White Plains, New York, and as part of her maternity training delivered many babies – unassisted — in at-home births. She met women who had had several children and were desperate to avoid future pregnancies. Sanger had no idea what to tell them.

Soon after her 1902 marriage to architect and would-be painter William Sanger, she became pregnant, developed tuberculosis, and had a very difficult birth, followed by a lengthy illness and recovery. The young family moved from New York City to the suburbs for Margaret’s health, but two babies and eight years later, Sanger insisted that they return to the city.

In New York the Sangers were part of a left-wing circle that included John Reed, William “Big Bill” Haywood, Lincoln Steffens, and Emma Goldman. Goldman had been smuggling contraceptive devices into the United States from France since at least 1900 and greatly influenced Sanger’s thinking. Sanger joined the Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World, working with other radicals to provide support for its strikes.

Sanger also returned to nursing, working as a visiting nurse and midwife at Lillian Wald’s Henry Street Settlement in the Lower East Side. There, again, women repeatedly asked her how to prevent future pregnancies. In those days, poor women tried a range of quack medicines and dangerous methods to end pregnancies, including the use of knitting needles. After one of Sanger’s patients died from a self-induced abortion, she decided her life’s mission would be fighting for the right of low-income women to control their destinies and improve their health through family planning.

After visiting France to learn more about contraceptive use, Sanger returned to the United States and launched a newsletter, the Woman Rebel, in 1914, with backing from unions and feminists. As Sanger and her friends sat around her dining room table addressing newsletters, they brainstormed about what to call their emerging movement for reproductive freedom. From that conversation, the term “birth control” was born. Encouraging working-class women to “think for themselves and build up a fighting character,” Sanger wrote that “women cannot be on an equal footing with men until they have full and complete control over their reproductive function.”

Sanger began writing on women’s issues for the Call, a socialist newspaper. She expanded her columns into two popular books, What Every Mother Should Know (1914) and What Every Girl Should Know (1916), and later wrote an educational pamphlet called Family Limitation that would sell 10 million copies in thirteen languages. Around this time, Sanger wrote a column on the topic of venereal disease and went up against United States postal inspector Anthony Comstock, a one-man army against all things sexual.

In 1873 Congress passed the Comstock Law, which made illegal the delivery or transportation of “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” material and banned contraceptives and information about contraception from the mail. When postal officials refused to allow the Call to be mailed with the offending column, the paper responded by leaving empty the space where Sanger’s article would have appeared, except for the title: “What Every Girl Should Know – NOTHING!” And when Comstock seized the first few issues of the Woman Rebel from Sanger’s local post office, she got around him by mailing future issues from different post offices. Thousands of women responded to the newsletter, anxious for information on contraception.

Sanger received an arrest warrant for distributing the Woman Rebel and ended up in court. With very little time to prepare her defense and faced with a judge who seemed hostile to her cause, she decided to jump bail and flee, alone, to England.

After a year in exile, Sanger returned to the United States in 1916. By then, Comstock had died, and Sanger hoped that the laws might not be so vigorously enforced and that she might not have to stand trial. A well-publicized open letter to President Woodrow Wilson, signed by nine prominent British writers, including H. G. Wells, praised Sanger and her work. She gained more sympathy when newspapers reported that her five-year-old daughter, Peggy, had died suddenly of pneumonia. In the face of public pressure, the government dropped the case, though the laws remained on the books.

That year Sanger opened the nation’s first birth control clinic, in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, primarily serving immigrant Jewish and Italian women. Sanger, her sister Ethel Byrne (a registered nurse), and Fania Mindell (who helped translate for the immigrant patients) rented a small storefront and distributed flyers written in English, Yiddish, and Italian advertising the clinic’s services. Sanger smuggled in diaphragms from the Netherlands, but she couldn’t recruit doctors to fit them properly in her patients. Although doctors were allowed to provide men with condoms as protection against venereal disease, it was illegal to provide women with contraception.

Sanger and her sister provided the services instead. The first day the clinic opened, they saw 140 people. Women –some from as far away as Pennsylvania and Massachusetts — stood in long lines to avail themselves of the clinic’s services. After nine days, the vice squad raided the clinic, and Sanger spent the night in jail. As soon as she was released, she returned to work. Again, the police came, and this time they forced her landlord, a Sanger sympathizer, to evict them.

Following the eviction, Sanger, her sister, and Mindell were arrested for “creating a public nuisance” and went on trial in January 1917. Sanger was convicted, but the judge offered her a suspended sentence if she agreed not to repeat the offense. She refused. She was then offered a choice between a fine or thirty days in jail; she chose jail. She appealed the decision, but a year later the New York Court of Appeals upheld her conviction. However, the judge ruled that physicians could legally prescribe contraception for general health reasons, if not exclusively for venereal disease.

Sanger continued writing and advocating for reproductive health rights, founding (in 1921) the American Birth Control League, the precursor to Planned Parenthood, and (in 1923) the Birth Control Clinic Research Bureau, the first legal clinic to distribute contraceptive information and fit diaphragms, under the direction of women doctors.

But it was not until 1936 that a federal district court in New York City ruled that the U.S. government could not interfere with the importation of diaphragms for medical use. In 1952, Sanger helped found the International Planned Parenthood Federation. She spent the end of her career raising money for research, in efforts that contributed to the development of the birth control pill.

Feminist and progressive reformers were divided over Sanger’s crusade for birth control. Alice Hamilton, Crystal Eastman, and Katharine Houghton Hepburn (actress Katherine Hepburn’s mother) supported Sanger, but others, such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Carrie Chapman Catt, thought that birth control would increase men’s power over women as sex objects.

But what about Ben Carson’s accusations – similar to ones that Herman Cain made in 2012 when he was running for the Republican presidential nomination — that Sanger targeted black women in her birth control crusade?

Their claims are false, even though they are frequently repeated.

In 1930, with the support of the prominent black activist and intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois, the Urban League, and the Amsterdam News (New York’s leading black newspaper), Sanger opened a family planning clinic in Harlem, staffed by a black doctor and black social worker. The clinic was directed by a 15-member advisory board consisting of black doctors, nurses, clergy, journalists, and social workers.

Then, in 1939, key leaders in the black community encouraged Sanger to expand her efforts to the rural South, where most African Americans lived. Thus began the “Negro Project,” with Du Bois, Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. of Harlem’s powerful Abyssinian Baptist Church, journalist and reformer Ida Wells, sociologist E. Franklin Frazier, educator Mary McLeod Bethune, and other black leaders lending support.

Sanger explained that the project was designed to help “a group notoriously underprivileged and handicapped…to get a fair share of the better things in life. To give them the means of helping themselves is perhaps the richest gift of all. We believe birth control knowledge brought to this group, is the most direct, constructive aid that can be given them to improve their immediate situation.”

Sanger viewed birth control as a way to empower black women, not as a means to reduce the black population. And according to Hazel Moore, who ran a birth control project in Virginia in the 1930s under Sanger’s direction, black women were very responsive to the birth control education under the “Negro Project.” At the same time, however, a number of Southern states began incorporating birth control services unevenly into their public health programs, which were rigidly segregated, providing health services to blacks that were poorly funded.

To the detriment of her reputation and to the cause of reproductive freedom, Sanger was also attracted to aspects of the eugenics movement. In the 1920s and 1930s, some scientists viewed eugenics as a way to identify the hereditary bases of both physical and mental diseases. Many people across the political spectrum –including Winston Churchill, Herbert Hoover, Theodore Roosevelt, George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and even Du Bois – believed that humanity could be improved by selective breeding.

Others, however, viewed it as a means to create a “superior” human race. But eugenics and contraception did not go hand in hand. The Nazis opposed birth control and abortion for healthy and “fit” women in their effort to promote a white master race. In fact, Nazi Germany banned and burned Sanger’s books on family planning.

Although the eugenics movement included some who had racist ideas, wanting to create some sort of master race, “only a minority of eugenicists” ever believed this, according to Ruth Engs, professor emerita at the Indiana University School of Public Health and an expert in the movement.

At the time that Sanger was active, Engs wrote, “the purpose of eugenics was to improve the human race by having people be more healthy through exercise, recreation in parks, marriage to someone free from sexually transmitted diseases, well-baby clinics, immunizations, clean food and water, proper nutrition, non-smoking and drinking.”

Race-based eugenics was practiced in the United States as well. Blacks were used as unwitting subjects for medical experiments, such as the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiment conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service from 1932 to 1972. Poor and especially black women were frequently sterilized in hospitals, often without their knowledge.

Many of the eugenics movement’s leaders were racists and anti-Semites who promoted involuntary sterilization in order to help breed a “superior” race.

But Sanger was not among them. Her primary focus was on freeing women who lived in poverty from the burden of unwanted pregnancies. She embraced eugenics to stop individuals from passing down mental and physical diseases to their descendants, whatever we may think of that practice today. In a 1921 article, she argued that “the most urgent problem today is how to limit and discourage the over-fertility of the mentally and physically defective.”

By today’s standards, these words are certainly troublesome, but Sanger always repudiated the use of eugenics on specific racial or ethnic groups. She believed that reproductive choices should be made by individual women. According to Jean H. Baker, a history professor at Goucher College and the author of a biography of Sanger, the women’s equality activist “was far ahead of her times in terms of opposing racial segregation.”

Neither Sanger nor Planned Parenthood sought to coerce black women into using birth control or getting sterilized. In the 1920s, when anti-immigrant sentiment reached a peak and some scientists justified restricting immigration (as in the Immigration Act of 1924) by claiming that some ethnic groups were mentally and physically inferior, Sanger spoke out against such stereotyping.

Sanger wanted women to be able to avoid unwanted pregnancies. She worked for women of all classes and races to have that choice, which she believed to be a right.

Even so, over the years Sanger’s flirtation with eugenics has provided fodder for attacks from the right. As several of her biographers have documented, a number of racist statements have been falsely attributed to Sanger. Carson’s most recent anti-Sanger diatribe is simply the latest in a long string of bogus accusations against her and Planned Parenthood, designed to score political points with the GOP’s base.

And what about his claim that most Planned Parenthood clinics are in black neighborhoods? According to the Guttmacher Institute, only about 110 of Planned Parenthood’s 800 clinics are in areas where blacks make up over 25 percent of the overall population.

Planned Parenthood establishes clinics based on where medical needs—including a shortage of primary care providers and a high poverty rate—are the greatest. They provide women with birth control information and services, test women for infections, offer antibiotics, pregnancy tests, and Pap smears, and teach women how to do breasts self-exams. They also provide abortions and give women an alternative to ending pregnancies in unsafe conditions.

And what about Congressman O’Brien’s claim that Sanger was a Klu Klux Klanner? Totally false, Politifact found.

Sanger’s efforts drew many prominent supporters and had a huge impact in changing America.

In 1961, Estelle Griswold, executive director of Planned Parenthood of Connecticut, opened a clinic in New Haven with Dr. C. Lee Buxton, a physician and professor at Yale’s medical school. They were arrested in November 1961 for violating a state law prohibiting the use of birth control. Their case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in 1965 ruled in Griswold v Connecticut that the law violated the right to marital privacy. The case established couples’ right to birth control and women’s right to privacy in medical decisions, which paved the way for Roe v Wade, the landmark 1973 Supreme Court ruling that recognized a woman’s right to choose an abortion.

Sanger’s work with African Americans earned praise from Martin Luther King, Jr., who received Planned Parenthood’s Margaret Sanger Award in 1966. In his acceptance speech, he said “There is a striking kinship between our movement and Margaret Sanger’s early efforts.”

Through the 1960s and early 1970s, the Republican Party embraced family planning and abortion. Prescott Bush, a Republican Senator from Connecticut and father and grandfather to the two Bush presidents, was Planned Parenthood’s treasurer in the late 1940s. Senator Barry Goldwater, the GOP’s 1964 presidential candidate, supported Planned Parenthood; his wife was a board member of its Phoenix affiliate. In 1968, President Richard Nixon advocated federal funding for family planning. When he was a Congressman from Texas, George H. W. Bush argued that “We need to make family planning a household word.”

After Roe v Wade, however, Republican operatives and the Religious Right activists joined forces to promote a “family values” agenda against the political and cultural victories of the women’s rights and civil rights movements. Since then, conservatives have steadily sought to restrict a woman’s right to an abortion. In recent years, that effort has escalated into a fervent crusade, including state-level ballot measures to limit abortions and daily vigils outside clinics that perform abortions. The movement’s most extreme wing has engaged in bombings at clinics and even encouraged (and in some cases carried out) the assassination of those who work at abortion clinics.

Ironically, Planned Parenthood is more popular than any Republican candidate. According to a recent NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll, Planned Parenthood’s favorability rating across party lines is 45 percent while the GOP’s approval rating is 28 percent.

The group’s popularity – despite the barrage of attacks against it – shouldn’t be surprising. One-fifth of all American women have gone to a Planned Parenthood facility. In 2013, Planned Parenthood affiliated clinics provided nearly 10.6 million services to 2.7 million women and men, including contraception, abortions, and other women’s health services, including 900,000 annual cancer screenings and millions of tests for sexually-transmitted infections. Abortion services make up just three percent of Planned Parenthood’s activities, and existing federal law prevents any federal funding from going toward this portion of their work.

Planned Parenthood’s services are particularly important to poor and lower-income women. At least 78 percent of its patients have incomes at or below 150 percent of the federal poverty level. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that 650,000 women would lose access to health services if the federal government eliminated its funding for Planned Parenthood. Less access to birth control would lead to more unplanned pregnancies. In 18 states surveyed, Planned Parenthood provides 40 percent of birth control services. In 11 other states, that figure is even higher. Permanent defunding, the CBO says, would increase federal spending by $130 million over 10 years. Most of the increase would be the result of thousands of unwanted births needing to be covered by Medicaid, as well as coverage of the children’s healthcare.

Captured by its most conservative elements, the Republican Party jumped on the anti-abortion bandwagon. This explains the attacks on Planned Parenthood by the current crop of GOP presidential candidates. And it explains why Margaret Sanger — who founded the birth control movement and Planned Parenthood to allow women to make their own reproductive decisions – is back in the news.