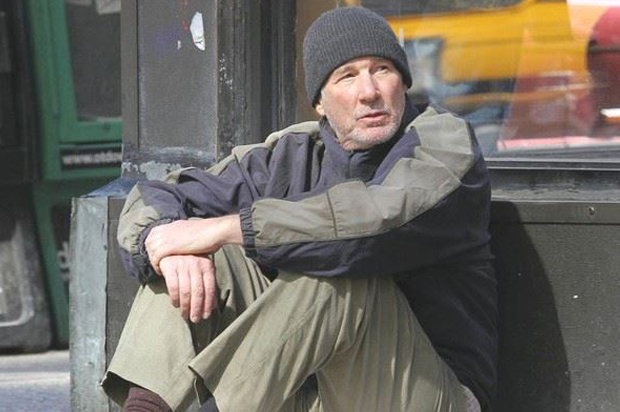

A photograph of actor Richard Gere, homeless man, has gone viral. He’s not actually homeless: he was in character for a recently-released film called “Time out of Mind“. In it, Gere plays a mentally ill homeless man trying to reconnect with his daughter, played by Jena Malone. A fan had posted the image of the actor to the “Unofficial: Richard Gere” fan page on Facebook, along with the comment: “When I went undercover in New York City as a homeless man, no one noticed me. I felt what it was like to be a homeless man. People would just past by me and look at me in disgrace. Only one lady was kind enough to give me some food. It was an experience I’ll never forget.” (Read Gere’s interview with Salon from last month, where he talks about the experience.)

To date, the image has received 1.55 million likes on Facebook and has been shared over 640,000 times.

There were also hundreds of comments, many of them confessional, including the phrase: “I was homeless for a while…” After reading them, it’s difficult to avoid the impression that homelessness is not only a lot more common than many realize, but the kind of person who becomes homeless increasingly seems to be, well, ordinary. Not a veteran suffering from PTSD, an undiagnosed schizophrenic, or an alcoholic drinking his way out of this world, but a teenager at the top of her class whose family has fallen on hard times, or a woman with a steady job that doesn’t pay enough to cover food and rent.

As Katharine Patterson recently wrote for Quartz: “The rent is so high in San Francisco that I’m a software engineer and I live in a van.” Technically, she is homeless, or at the very least, home-lesser than usual. Yet “people don’t report me,” she notes; “neither do they assume I’m a vagrant. They smile and ask if I need anything.” She’s aware that she largely escapes harassment because she is a young white woman. Whereas a few months ago, security officers at the Boston Public Library harassed me because I fell asleep in a comfy chair in the reading room. This is apparently verboten, because the homeless people hovering by the entrance might get the idea they can use the library as a sleeping room. Eventually, the harassment got so annoying that I packed up and left–the irony being that I was at the library to participate in a public talk regarding (the lack of) diversity in kid-lit, which to my mind includes the lack of economically disenfranchised and rural characters.

And no, I didn’t tell the officers I’d been invited to speak at the event, or point to my name on the flyers, because that really wasn’t the point. I didn’t mind being mistaken for a homeless person. I minded being treated like one. That disdain, I think, is the part that shocked Gere the most when he experienced New York City in character. When others think you are powerless, you see the worst of human nature–and it’s not the homeless whose behavior repulses you.

Talk to working-class people, and the phrase, “I used to be homeless,” burbles up a lot, but typically it is confessed only after that person has a steady job. In other words, after the happy ending is secure, for having been homeless is very different from actively being homeless, which is tantamount to declaring yourself a communicable disease. Yet the Cinderella story, which finds a homeless person rising to dazzling fame and fortune, applies to Jennifer Lopez, Jim Carrey, Halle Berry, Shania Twain, and David Letterman, among others. Their against-all-odds success stories reinforce the myth that all you need to succeed is to pull yourself up by your bootstraps, proving that the American Dream (as told by kid-lit writer Horatio Alger) really can come true.

Given the popularity of that arc, you’d think there’d be more Hollywood films about homelessness. There are a few: “Trading Places,” “Down and Out in Beverly Hills,” “Being Flynn” (based on Nick Flynn’s memoir, “Another Bullshit Night in Suck City“), “The Soloist,” and now, “Time Out of Mind.” But it is exceptionally difficult to get films made about the subject because the public doesn’t want to see it. The subject is too depressing, too vulnerable to the exploitations of poverty tourism, too readily transformed into a moralizing parable about the virtues of giving.

The subject is a natural fit, however, with singing the blues: back in 2007, the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Jon Bon Jovi, Pete Seeger, and Dan Zanes contributed their talents to create the album, “Give Us Your Poor,” to help support the Give Us Your Poor initiative at UMass-Boston. One of the people involved with that album was my French, mixed-race brother-in-law. He was homeless for decades, hanging out with some of the biggest names in the ‘70s Boston music scene while living on the streets, and organizing subversive concerts performed by friends and comrades at the shelter he later worked at as a counselor. Partially documented by him using film, some performances from ’87-’92 have been digitized and edited as “Voices From a Shelter for Men.” Tim Hobson’s singing voice (starting around 16.14) is painfully good, and Jonahson Turner’s songwriting is impressive (listen to “Great Big Brains” starting around 33.45.) Music gives the homeless a voice that others want to listen to: these songs deserve to go viral, as a reminder that the homeless are human too. Recently, Miley Cyrus has been actively raising awareness of the endemic problem of teen homelessness by founding the “Happy Hippie” non-profit focused on homeless LGBTQ youth. She plans collaborations with various musicians, including Joan Jett and Ariana Grande, in support of the foundation.

Yet it’s precisely because homelessness is now so terrifyingly proximate to the precarious economic situation facing the middle class that it’s become a cultural taboo. Normalizing the experience threatens the psychological barrier between “us” and “them,” yet on the economic plane, the distance between respectability and homelessness is vanishingly thin. In 2009, the National Coalition for the Homeless published a study that concluded: “Two trends are largely responsible for the rise in homelessness over the past 20-25 years: a growing shortage of affordable rental housing and a simultaneous increase in poverty.” Combine these two trends with eroding work opportunities, decline in public assistance, and lack of affordable healthcare, and the overall picture becomes grim. One layoff, one illness, one divorce, and that homeless person is you. Suddenly, thanks to Richard Gere, a million or so people on social media have realized that anyone can be homeless, and even a man as famous for his looks as Gere can suddenly become invisible when he sits raggedly on the sidewalk, expecting nothing from anyone, not even attention.

Gere is not active on social media; he has no Facebook account of his own. In response to the outpouring of interest in his “homeless” condition, he held a Q&A today on Jena Malone’s Facebook page, hosted with “Time Out of Mind” director Oren Moverman. Today is also Day Two of Equity Summit 2015 taking place at the Westin Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles. This is a national meeting convened in order to address the problem of widening income inequality in the U.S., lack of affordable housing being one of the leading factors contributing to homelessness. Via phone, I spoke with Robin Comey, coordinator of the Early Childhood Collaborative in Branford, Connecticut. She is one of a delegation of 60 people from Connecticut attending this three-day event in Los Angeles. What was one of the first things she noticed upon arriving in the city where dreams of stardom come true for a lucky few, yet is also the “meanest” city when it comes to treating its homeless as criminals? “I’ve seen a lot of homeless people here, even compared to Hartford.” Her wry conclusion: “Housing out here must be expensive.”