The idiosyncratic Seattle-based writer David Shields was startled as he followed the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq through the New York Times’ visual representation. “At least once a week I would be enchanted and infuriated by these images, and I wanted to understand why,” he writes in the introduction to his new book. So he spent months going over every front page war photo since the wars began — more than 1,00 images.

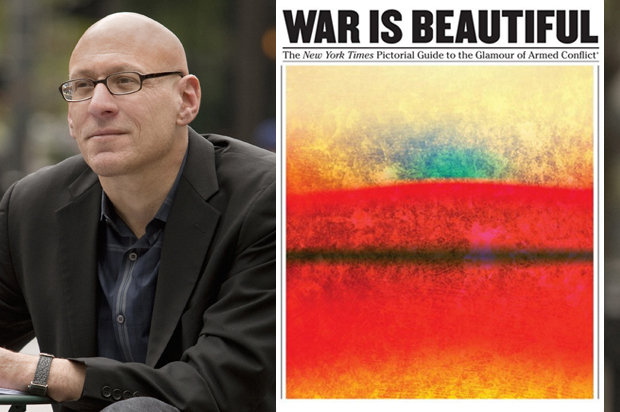

The result of his inquiry is “War is Beautiful: The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Conflict.” It’s a twisted kind of coffee-table book: Most of “War is Beautiful” reproduces the newspaper’s images, one per page, in between brief pieces by Shields and art critic Dave Hickey, who argues that “combat photographs today are so profoundly touched in the process of bringing them out, that they amount to corporate folk art … They are no longer ‘lifelike,’ but rather ‘picture-like.’”

Shields also sets up the images with brief quotations. For the most part, though, he lets the images speak for themselves.

Salon asked Shields — whose acclaimed book, “Reality Hunger,” is a collage made up mostly of other people’s quotes — to show his hand a bit. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

You talked about, in your introduction, feeling a mixture of “rapture, bafflement and repulsion” when you looked at these photographs. How did those emotions all come together for you? What provoked that strange brew?

You know, as I say on the front of the book, I’ve subscribed to the paper for decades, over the last 20 years … I find myself eagerly awaiting for paper, my little war-porn addiction, and that just seemed to me fundamentally problematic, fundamentally wrong. What was the problem in me, in my head, in my psyche? Was there a problem in the paper, was it in the exchange between the paper and me?

And I thought that it’s that law, you know — if you see something, say something. I was seeing something, my eye was noticing this overwhelming pattern of impossibly beautiful photographs that conveyed not the war itself but the war that is a kind of heck, you know, according to the Times, war is heck. What was going on? Was I under-reading the pictures, misreading the pictures? Demanding the pictures be more gritty than they can possibly be? I wanted to investigate that question.

I was open to course correction to be proven wrong and I hoped that I would be proven wrong; not many American writers are printing and publishing a full book that is a takedown of the New York Times. It tends not to be the wisest career move. So, I was hoping, frankly, that I’d be course corrected; I’d find hundreds or dozens of photographs to prove me wrong. But I ended up pulling, with the help of photo assistants, I looked at 4,500 cover photographs from October ’97 to essentially now. I found 1,000 war photos, 700 that to me for my criterion, of you might say, wrongly beautiful photographs. Virtually no photograph that conveyed the horror of war. For the paper of record, the first draft of history, all the news it fits to print, it seems to me that that was problematic and worth pointing out.

I think the pictures are ravishingly beautiful, they’re just Gerhard Richter level, a Jackson Pollock level, Mark Rothko level gorgeousness, but first of all, to me, they seem problematic representations of Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Secondly, they were almost never balanced by [anything] that conveyed anything other than war’s really cool, really glamorous, really bloodless. They feel to me kind of scarily like military recruitment posters. So, so beautiful.

I don’t know if you have the book there in front of you, but page 58 has been cropped from a much larger photograph, that has a sort of Richter-like beauty. Picture on 50 looks like an Andrew Wyeth. I think your question was how was that exact cocktail of ravishment and fury and resentment come about. I would be hard pressed to pull them all apart, I found myself loving these photographs, coming to realize they were probably oddly tied to war.

This was a series of wars the Times was ostensibly covering, but was to me problematically promoting, and if this had been say, USA Today or the Wall Street Journal, or the New York Post, it would make sense. But this is a paper that, you know, is thought to be neutral or the Fourth Estate, even center-left, and these pictures just to me did not fit what strikes me as responsible journalism. They’re essentially jingoistic flag waving. It’s essentially war cheerleading under the guise of photojournalism. That’s how the book came to be.

Has that quality you described been part of American war photography all the way back? Do we see images like this from Vietnam or World War I or II, or is this a different kind of aesthetic that’s come in in 21st century wars?

It is. I would definitely say it has changed, and I think that Dave Hickey’s afterword in the back of the book explains it awfully well. From Matthew Brady and the Civil War through say, Robert Capa in World War II to people like Malcolm Brown and Tim Page in Vietnam. There was, seems to me, a kind of war-is-hell photography where the photographer is actually filming from life. I think what Hickey argues, pretty persuasively, in the afterword, you know swipe photography which in a way gave rise to abstract expressionism of Rothko, Pollock, Diebenkorn, Richter, has completely tilted the field so that now to me, photographers who have first of all, been embedded by the military. They’re sending pics digitally, but above all the photo editors and photographers in my view, and Hickey’s view, have gone to school on neo-realist painting, on photo realists painting, on pop art, on abstract expressionism.

And picture after picture is a kind of footnote to art history tropes. As Hickey said, the pictures are no longer being taken from life observed, they’re being sort of pulled from art history archives.

To me, there’s almost no lived life, there’s almost no grit, there’s almost no blood, there’s almost nothing of the horror of war. Instead there’s a kind of beautiful but extremely empty composition. And so, to me, there’s a whole series of factors — the rise of hyper digital culture, the decline of print journalism, embedded journalists. But above all, photographers and photo editors, in my view, are less observing the war in front of them — which is probably a complete bloody mess — and instead, trying to produce photographs, that first of all, are beautiful footnotes to say, abstract expressionism. And secondarily, perhaps more importantly, are palpable to the American and specifically, the New York Times reading public.

There’s a kind of compromise going on between us as readers, the Times as publishers and the U.S. government. I think we, as viewers, as readers, as subscribers are complicit as well. These are staggeringly beautiful photographs which I find myself complicit for having gobbled up for too many years.

Right, if we enjoy the photographs, if we respond to their aestheticism, we’re complicit as well.

It took me way too long. It took me from ’97 to say, 2007, 2008, 2010 to finally say I’ve got to actually study these pictures. I wish I had produced this book 10 years ago, whereas now it’s slightly after the fact. I’m sort of hoping people will learn, including myself.

This is how we are lambs that are bred to slaughter, this is how we buy war propaganda. I think it’s an open question. It’s not like the Times was saying … I don’t know very much about the inner workings of the Times, it’s not like a kind of socio-political text. Here are 64 photographs that are disarmingly beautiful, like, “What are they doing on the front page of the New York Times as war photos?”

As to whether the Times was fully conscious of what they’re doing, or unconscious because of the result of hyper digital culture, it’s the result of pics being sent digitally from the battlefield, is the Times essentially is currying favor with the U.S. government. It’s all those things into a very problematic cocktail, is the books’ argument.

You have a short essay in the beginning, a shortish essay by Dave Hickey in the end, otherwise it’s all photographs by other people. And the book of yours that a lot of people know, “Reality Hunger,” is primarily made up of quotes, from other people. I wonder if your sense of the traditional literary essay and non-fiction book is exhausted or at least exhausted for you. You’re using these alternate ways of making an argument or building an essay.

You trace those things nicely. It seems a little grandiose of me to track the links between this and my previous book, or books, in a way that’s better left for someone else to do. But I clearly see the connection — in a way, I feel as if what these photographs suffer from is precisely a lack of reality hunger. They seem to have a kind of style hunger.

There’s that wonderful line, I forget who said it, “The enemy of art is taste.” And these pictures are just so tasteful, they’re very tasteful, you can look at the pictures while you have your morning coffee and croissant. They make you feel like, “Oh yeah! I’ve become educated about war.”

I am exhausted by traditional memoir. I am exhausted by the architecture of the conventional novel. I’m really interested in the new nonfiction. I think the hyper-digital culture has changed our brains in ways we cannot begin to fathom. So, whether a book idea, like say, “That Thing You Do With Your Mouth” — it came out in June with McSweeney’s, or another book I did, “Life is Short,” in April, or another book I did with my former student called “I Think You’re Totally Wrong: A Quarrel” [that] came out in January — here are a whole series of books I’ve done trying to collapse the distinction between fiction and nonfiction, to overturn the laws regarding appropriation, and sort of suggest news way writers can turbo-charge in contemporary nonfiction.

I just can’t read the way other people can, these tediously elaborated books. I could’ve written a 300-page critique explaining how every photograph is related … I just think we’re smarter than that. I really like books that don’t patronize the reader and rather give the reader tools to work with then let the reader make the connections you’ll help them make. I’m very fond of this phrase: “Collage is not a refuge for the compositionally disabled.” If you put together the pieces in a really powerful way, I think you’ll let a thousand discrepancies bloom.

I’ve very interested in a book as IED; I think this book is an improvised explosive device, and I just want to generate conversation. I want to create trouble, and I want to prick out our consciousness, including my own.

I think a noble definition of art is to recreate trouble. Flaubert said the value of art can be measured by the harm spoken of it. And I think a lot of what my critique is of the Times is that those pictures show no harm. And I am arguing for a photojournalism, a literary art, and a visual art that faces human harm more straightforwardly. War is hell — not war is heck — to repeat that particular trope.