It’s the most frequently invoked phrase in American political life. “The American people have a right to know …” “The American people are asking where their hard-earned tax dollars are going.” “The American people are waiting for the Secretary of State to come clean about what she knew.” So, when we get right down to it, what, if anything, does this greatly overused phrase mean? What do the American people actually want to know?

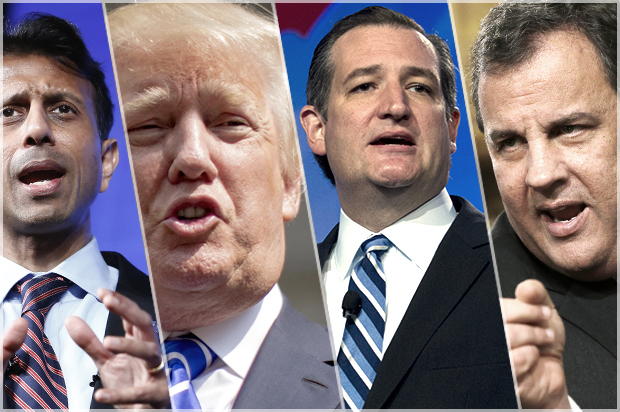

Let’s begin with something concrete. In “founder-speak” (referring colloquially to our national beginnings), “the American people” was a loose term to describe the formation of public opinion. This was a moment in history when “sovereign people,” a largely theoretical construct, contested the crowned sovereigns who then ruled most of the planet. It was not yet the tool of the average demagogue (say, Ted Cruz) or the average attack ad (“The American people have had enough of….”). Let’s see if we can travel from then to now, and make better sense of the history of a phrase.

In July 1775, not long after the battles of Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill, the Second Continental Congress petitioned King George III. In the interest of reconciling the United Colonies with the parent state, even after the occasion of much bloodshed, the earnest petitioners bade him (who was yet their king) to make “such arrangements as your Majesty’s wisdom can form for collecting the united sense of your American people.” If he ceased thinking of them as rebels, he would soon understand that their very reasonable desire was a return to the mild government they had previously enjoyed under their sovereign. The patient members of Congress who signed the petition presumed that a sympathetic connection could yet be found if a reliably objective representative of the crown somehow took the pulse of these distant subjects en masse.

In Federalist 37, James Madison wrote: “Stability in government is essential to national character and to the advantages annexed to it, as well as to that repose and confidence in the minds of the people, which are among the chief blessings of civil society.” As the Constitution was being framed, “national character” doubled for “the American people,” and was typically linked to the informed (moral as well as intellectual) choices they made in identifying the public interest with those individuals they considered worthy of office. National character was meant as an expression of the unity of interest and rights in America; it bespoke a desire to be collectively honest, introspective and visible to the outside world as a character-driven republic.

Even as we acknowledge all partisan dysfunction, this ideal about who we are has never left our vocabulary. The airwaves draw us to all manner of “Breaking News”: verbal gaffes, inaccurate comparisons to Hitler, hints of scandal. Campaign chatter threatens to burst the collective eardrum. Amid this unfiltered noise, the ultimate authority, “the American people,” lies in reserve, and we expect to hear it invoked as reassurance that a comprehensive viewpoint exists, and that we matter.

Readers might be surprised to learn that in the early years of the republic, “the American people” was not used nearly so much as it is now, nor as all-embracingly. Each Fourth of July, newspapers dutifully took note of the general spirit of camaraderie that “distinguishes the American people as one family.” Beyond national celebration, politicians did not rely on this terminology.

That is not to say campaign season was ever truly a time of rational discourse, or that presidential wannabes were uniformly acknowledged as the best men for the job. In some ways, the 1848 election was like 2016 in the questions being asked about candidate qualifications and concerns aired with respect to voters’ suggestive minds. In that election year, a newspaper in east Texas — which state had only joined the Union three years earlier — took issue with Whig candidate Zachary Taylor, a victorious general who rode to fame in Mexico but had an ambiguous political identity. “The American people are notorious for their good common sense, and practicality,” went the editorial, “yet they are as easily humbugged as any people on the face of the earth.” To see General Taylor elected “would prove that the people were liable to be humbugged” — in other words, made the victims of a hoax, their political innocence imposed upon. Did the presidential hopeful even understand “the fundamental principles, and complicated machinery by which this great Union is held together?”

The editorialist delivered a stern warning. No one actually knew whether Taylor’s success in the late war was due to “good Generalship, the insignificance of his enemy, the chivalry of his own troops, the act of Providence, or a combination of these.” The desire to believe the best about a supposed savior had overtaken reasoned evidence. A political unknown’s “influence over the American people” was, the columnist insisted, “dangerous to their liberties, and degrading to their character as intelligent people.”

The year 1848 is not remote, in terms of the perils inherent in democracy. The Texas critic was an early incarnation of today’s questioners who wonder whether a real estate mogul or a neurosurgeon with no experience representing the public interest deserve to be seriously considered for high office. The American people continue to be “humbugged,” only now it comes courtesy of an instantaneous, visually aggressive format. As many have observed, we are glued to our screens, and the message is never neutral.

Part of the reason why “the American people” sounds so good dates to the latter part of the nineteenth century, when the phrase was often invoked to describe a superior race. “We are emphatically a people of nerves,” declared the American Magazine in 1888. “Visitors from other lands are astonished at the fierce activity that pervades our most insignificant actions.” The energy embodied in the American character was due in some measure to the “American climate, which teaches in a vigorous and obtrusive manner that quiet and rest do not form part of natural law in this country.” We remained young and wakeful. “Scarcely out of swaddling clothes,” ran this generally upbeat article, “we are called upon to stand squarely in competition with a thousand years of past, and show the old fogies a new thing or two.”

The country was in the midst of an immigrant deluge — the Statue of Liberty had just been dedicated. The writer predicted a future of “diluted” Americanness, the national essence weakened through the infusion of questionable foreign blood. Here we see shades of the nativist critique launched by Donald Trump, warning energetic Americans that they have to do something about Mexico’s “worst people” and warning voters to steer clear of “low energy” presidential candidates.

The American people were under attack. We hear the same catch-all out of politicians’ mouths day after day after day. Take Ted Cruz in Congress at the end of September: “There is a reason the American people are fed up with Washington. There is a reason the American people are frustrated. The frustration is not simply mild or passing or ephemeral. It is volcanic. Over and over again, the American people go to the ballot box, over and over again, the American people rise up and say the direction we’re going doesn’t make sense. We want change … and yet, nothing changes in Washington.” Almost every sentence is dominated by the same subject: the American people.

So, who are “We the People”? It depends, of course, on who a politician sees as likeminded, or poised to benefit most, from policies he (or occasionally she) espouses. Generation by generation, the popular, ill-defined term has been cheapened, so that it’s now taken as a throwaway line — except we are supposed to agree when poll-tested. But is that precisely true? It is arguable that its meaning became clearer in 2012, when GOP nominee Mitt Romney was widely seen as the candidate of the one percent, a greed-inspired corporatist oblivious to the life of the average voter. If a president is meant to intuit the just needs and wants of “the American people,” then candidate Romney failed to wear “the people’s” mantle comfortably.

President Obama has tended to use the phrase where it seems appropriate, as in promoting affordable healthcare, e.g., “I believe it’s time to give the American people more control over their health care and their health insurance.” He also likes to use the term to describe the essential warmth and neighborliness and resilience of his countrymen. In his First Inaugural Address, it was: “For as much as government can do and must do, it is ultimately the faith and determination of the American people upon which this nation relies. It is the kindness to take in a stranger when the levees break, the selflessness of workers who would rather cut their hours than see a friend lose their job …” But Rick Perry of Texas had the same take, when he announced his abortive candidacy last June: “The spirit of compassion demonstrated by Texans is alive all across America today. While we have experienced a deficit in leadership, among the American people there is a surplus of spirit.”

President Obama tends to avoid invoking “the American people” to inflame passions when he is defining himself in opposition to Republicans, but he can be a bit snarky, too. In the first debate with Romney, the one in which Obama fared so poorly, the Republican held forth: “The American people don’t want Medicare, don’t want Obamacare.” Confronting Romney’s call for reliance on private markets, and doubting the content of his “secret plan” to replace Obamacare, the incumbent said: “I think the American people have to ask themselves, is the reason that Governor Romney is keeping all these plans to replace secret because they’re too good?” Snarky, yes, but he legitimately defines the American people as those who must make up their minds before they vote. He also uses the hallowed term as a synonym for the broad middle class: “I also promised that I’d fight every single day on behalf of the American people, the middle class, and all those who were striving to get into the middle class.”

“The American people,” in recent Democratic parlance, have most often been job seekers. Running in 2015, Hillary Clinton has made a curious coupling in promoting economic fairness as her theme. It is: “President Obama and the American people’s hard work” that “pulled us back from the brink of depression.” Now let’s compare. Announcing for the presidency at his old high school, Chris Christie of New Jersey proclaimed that government entitlement programs were “lying and stealing from the American people.” Bobby Jindal of Louisiana, in announcing his candidacy, also went negative with the phrase: “It’s time to level with the American people. This president, and his apprentice-in-waiting Hillary Clinton, are leading America down the path to destruction.” Marco Rubio, on the occasion of his announcement, intimated — devoid of specifics — that once Obamacare was history and the tax code reformed, “the American people will create millions of better-paying modern jobs.”

We know political rhetoric is, almost by design, evasive. When they raise the term “the American people,” newsmakers have, for well over a century now, credited them with “dispassionate judgment.” Those who draw on the familiar construct operate on the pretense that “the people” have a marked, well-coordinated personality. But that’s much harder to accept today — America is simply too heterogeneous. Romney’s tone-deafness was not strictly a function of his extraordinary net worth; it reminded that one who possesses great wealth must credibly prove accessibility. The billionaire Trump, with his petulance, his childish antics, is still less remote from average folks than Romney. He thrives on crowds — all he cares about is that they cheer him. They may or may not be a good cross-section of the electorate, but they have as much claim to the designation “American people” as any more learned, respectful, policy-wonkish audience.

This is our problem. “The American people” are always presumed correct in their allegiances, but, in truth, they have never really been a reliable barometer of good government. Let’s not forget that they are regularly painted as victims, dupes — and have been ever since they were called upon to oust, at the ballot box, the “grasping and unscrupulous railway corporations” that were buying state legislatures in the early 1870s, ever since they ostensibly fell prey to the hyped-up warrior Zachary Taylor. It is odd (and a little frightening) that those in whom the protection of the principles of our republic are lodged — voters — are also adjudged the most susceptible members of the population.

We have the Internet, but “the American people” do not reside there either. Political blogs may draw fanfaronade; but few sites truly constitute a forum where ideas are calmly and usefully debated. Similarly, one has to wonder about the GOP itself, a political party that claims to speak for the American people and yet exhibits little interest in finding consensus — “consensus” being the founders’ ideal formula for expression of the people’s sovereignty.

It’s an all too obvious dilemma: We can’t police our elected representatives so that they think twice before claiming knowledge of what that fictive “We the People” think and it’s unlikely that there are a sufficient number of discerning voters able to separate the personal ambition of a candidate from their own best interests. Minimally, every candidate for public office should be asked by someone at every campaign event: “Why should I trust your judgment?” The answer should always be specifically focused. And it should not contain the words, “the American people.”