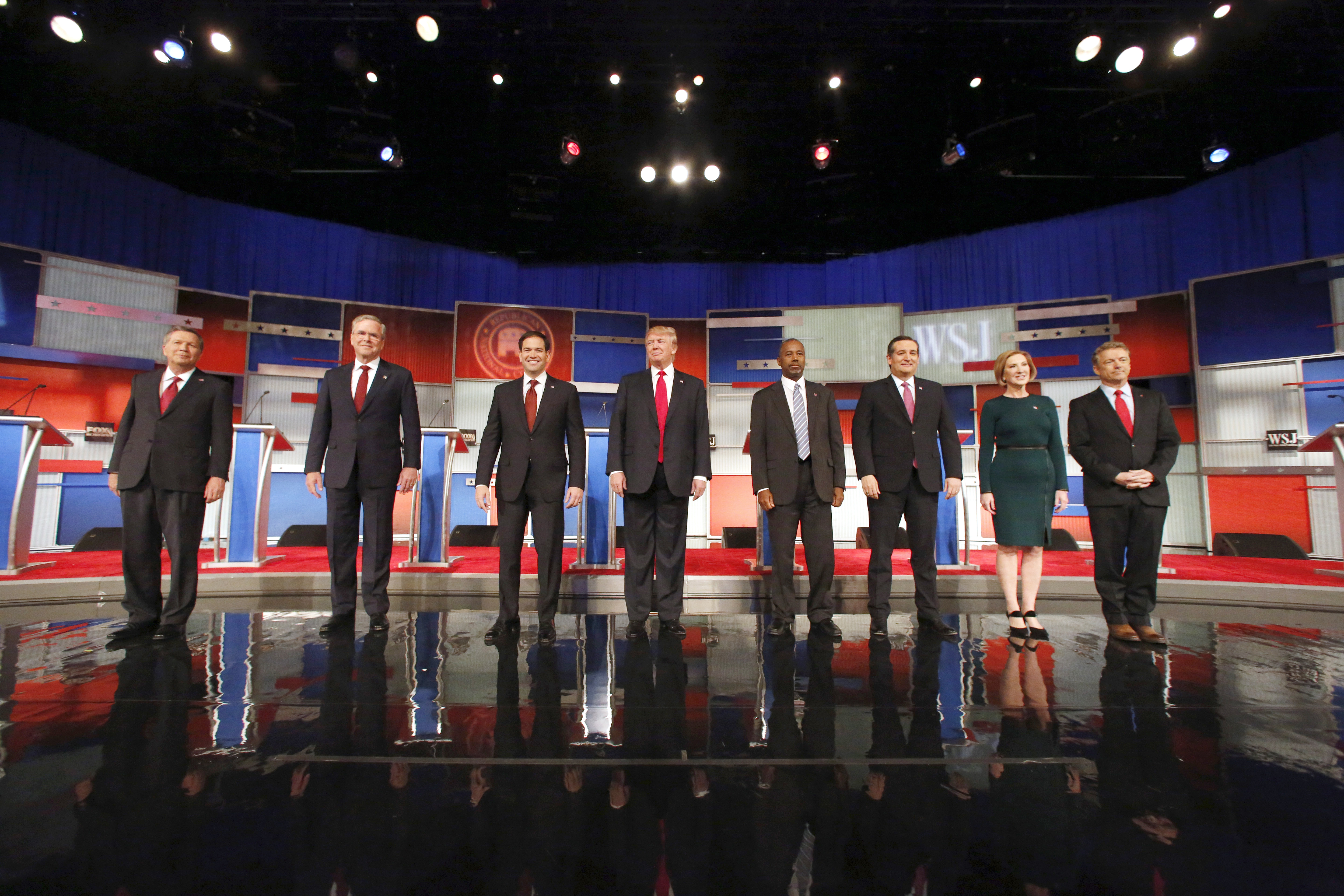

Disgruntled because of things debate moderators said, Republican presidential candidates convened earlier this month to construct a list of regulations for future debates, while the RNC publicly decried moderators’ “gotcha” questions and called for replacement moderators.

Let me reframe this scenario to make it more palatable for the present media climate: imagine the Republican presidential candidates are a group of college students petitioning to a regulatory authority because they were angered by oppositional speech and not mature enough to respond with poise and civility. So they sought to fire or replace oppositional voices with friendly voices that flattered their ideas and policies. The outcome they sought, then, was one in which their positions would go unchallenged and they could have nice feelings about themselves (unfortunately this is not a hypothetical; the next debate actually turned out that way).

Indeed, the candidates’ “demands” included prohibition of things like “candidate-to-candidate questioning” and “allow[ing] members of the audience to wear political messages,” while the RNC-generated talking points suggested moderators shouldn’t be allowed to ask candidates “gotcha” questions about things the candidates said and details of candidates’ policy proposals. While Ben Carson—who proposes a neo-McCarthyist policy of federal government policing of campus speech—rails against student protesters at Yale and University of Missouri, he and his fellow candidates appear unaware that, in full-on adulthood, they still haven’t learned the lessons they’re trying to teach.

It’s tempting to call this hypocrisy, but something else important is happening here. When it comes to speech and policy, the Republican candidates operate in a deep gulf between theory and practice. Carson has a sense of what free discourse in an ideal world should look like, and Trump has a sense that he can impose his foreign-policy will through sheer bravado, but when it comes to practical concerns—like policy details, or handling aggressive debate moderators—the ideal falls apart.

This is the point we need to understand if we’re going to understand the relationship between protests against racism at Yale and University of Missouri and the national politics of race and free speech. Free speech absolutism is an elegant idea premised on the expectation that a free, thoughtful, self-reflexive and educated populace has far more to gain from talking through offensive and oppositional speech than practicing censorship. The reality, however, is that very few of us—educated or not, young or old—turn out to be very good at operating under extreme or overwhelming verbal attack, or understanding when something is better left unsaid.

This doesn’t mean we should practice censorship, rather we should expect degrees of compromise as well as error when real-world forces like power imbalances, threats, and systematic offenses exert influence on what we mistakenly call “merely” the exchange of words and ideas.

For example, Tablet Magazine editor-at-large Mark Oppenheimer writes a thoughtful essay on free speech and protest at Yale in which he imagines an ideal scenario for the free speech absolutist:

Imagine a white male student wearing black face on Halloween (the kind of incident that has been reported). Then imagine that the next day 10 students, of all races and genders, show up at his dorm room, knock on the door, and, when he answers, ask to come in and explain to him, in tones calm but brutally honest, what was offensive about what he did.

That’s a fine response to imagine. But imagine, also, that the societal and institutional norms are casual racism. Imagine a wider media climate in which reporters and columnists have made it a national sport to treat your formative activism like it’s the new Maoism. Imagine millions of white people who know absolutely nothing about what it means to be a minority at Yale or Missouri reading about how you’re a crybaby and a wimp and a spoiled little brat.

Imagine you were standing there yourself at Halloween, wearing the black skin you can’t remove on the morning of November 1, and you see that kid in the blackface costume, and he’s surrounded by 20 other white kids at your predominately white institution, where even some of the faculty have suggested that it’s your responsibility to right this wrong.

Yes, I see the Donald Trumps of the world boasting about how they’d courageously stick up for themselves. But I suspect that when we’re really in those kinds of situations, it’s not only deeply challenging to speak truth to power (to borrow a phrase from those “SJWs” of the 1960s); I imagine it’s also, in some campus environments, physically dangerous (at Missouri, the racial slurs and death threats are a testament to how quickly free discourse can turn physical).

We should grant, then, that students are in college to grow intellectually, a substantial component of which is to work through the mutual limitations of theory and practice. Student activists do sometimes overreach, will sometime have regrets. But—at Yale, Missouri, and throughout the country in this year of close scrutiny of student activism—students also have a profound sense of the changes that must happen, the end of casual racism and misogyny at institutions that should be on the vanguard of progress.

To brand each of these campus controversies as only a “free speech issue” is to ignore the realities that render elegant theories of free speech a fine starting point, but an insufficient solution. To malign student activists as helplessly immature and underprepared for the harsh realities of the adult world is to ignore the fact that the adult world—from the Black-Friday parking lot to the cable news studio to the presidential debate podium—is itself depressingly deficient at practicing its free-speech idealism.