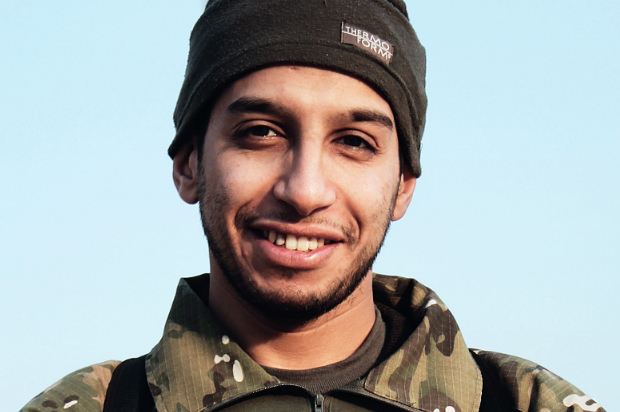

Last week’s Paris terrorist attacks, like most other large-scale crimes, has seen the original violence followed by a period in which the perpetrators are tracked down and killed, often one by one. Pick up a newspaper or glance at the Internet, and someone else has been found and killed. We see it in death penalty cases; we saw it on the hunting of Osama Bin Laden after the September 11 attacks. The latest example involves a raid that killed Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the suspected leader of the attacks.

Jailing someone who commits a crime – so he or she won’t break the law again — makes rational sense. But vengeance is a different kind of process, deeply rooted in our emotional system. Where does blood lust come from and what does it lead us to do? How ancient is the urge?

We spoke to Art Markman, professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Texas at Austin and co-host of the radio show “Two Guys on Your Head.” The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

All the reports of terrorists being hunted down and killed has my blood stirring. How far back does vengeance go in human history? And do we have any sense of where it comes from?

It goes back as far as we can remember. If you think about a lot of the early codes: What’s the idea of a eye for an eye? It’s vengeance. That’s just a reflection of the way that we do things.

Whenever somebody transgresses a norm, we want to correct it in some way. And there’s always a tension between two modes – one is punishment and the other is rehabilitation, which we see in our criminal justice system. Why do we punish offenders? You know?

You mean because it doesn’t solve the problem to kill someone – it doesn’t undo the crime or bring a victim back to life…

I think the data suggests that the death penalty is not a deterrent – the murder rate does not go down when there is or isn’t a death penalty. People who are gonna murder someone are not thinking, “Oh wow, I could get the death penalty for this.”

So if it’s not a deterrent, why are we doing it? It’s to satisfy a different urge – an urge for retribution, for vengeance. The idea is that if you commit an act that transgresses a norm, that you should suffer a consequence roughly equal in magnitude to what you did. Otherwise it’s not fair. And in fact it’s that particular definition of fairness that plays a role here. People will say, “It’s not fair that this person gets to keep on living, when my family member doesn’t.”

So this is a psychological thing, but also a social thing – it has to do with our social contract, who gets to be part of the community, who doesn’t.

Let’s take it away from murder for a second: We have now internalized that if you cause damage to a person of their property, that you pay money for that. There’s a civil court process, it costs money to have done something negligent. But that was, universally, not the way things happened. It was only a couple of thousands of years ago that we transferred from destroying somebody else’s property. “You kill my ox? I’ll kill your ox.” We went from that to transfers of money.

We still want there to be retribution in a way, but it doesn’t have to be physical harm.

In the case of these terrorists attacks, it’s an old-fashioned kind of vengeance – a hunting down and killing of the people responsible. There must be something in the human psyche, having nothing to do with society, nothing to do with physical changes, that wants to meet an offense with an equal offense.

Look at the animal kingdom. Forget about going to the African savannah. Look at dogs. Even dogs who like each other get on each other’s nerves – and snap [at each other]. And that’s a way of saying, “Cut that out.” Hopefully they calm down, but once in a while they get in a fight. They go at each other.

We’re animals – we’ve got the same [insincts.] This idea that we can create alternate means of vengeance is a cultural means of stopping the cycle of vengeance, the I-kill-one-of yours, you-kill-one-of-mine. Where does that end? Cultures have tried to solve that problem by creating legal systems to break that cycle. You kill someone… what we’ve agreed to do instead is have you arrested and incarcerated, and maybe after 30 years you’ll be put to death. You’re not getting the immediate vengeance.

[These cultural alternatives] are our way of avoiding just picking each other off.

Do we know where the urge for vengeance sits in the human brain? Is there a physical place where it originates?

Anything that’s emotional like that engages your emotional system. Those reactions are a reflection of the fact that structures deep inside your brain have been engaged and are trying to accomplish something. When you have a very strong, energetic reaction, what that’s saying is, “I very strongly want to perform this action.”

When you get very strong anger, it’s your emotional system saying, “I want to inflict harm on you.” Those are the brain systems that are old – they’re the ones we share with dogs and rats and deer. We engage that system, and then the rest of our brain – the cortex, particularly the frontal lobe – says, “Maybe, just maybe, that’s not such a good idea.”