Donald Trump has said and done some really disturbing things the last few days, even for him. For months he’s been talking about rounding up and deporting latino immigrants, depicting them as criminals, rapists and general “bad people.” But since the Paris attacks he’s gone full tilt against Muslims, indicating that he would close down mosques and have them register with the government. Then this past weekend he excused his thuggish fans for beating a Black Lives Matter protester at one of his events saying “maybe he should have been roughed up” and topped it off by re-tweeting a racist graphic. The DC press corps seems to have awakened to the unique racial and ethnic ugliness of Trump’s campaign and even a few Republicans mustered the nerve to condemn him.

But for all of his racist and eliminationist rhetoric last week, there’s something else he said that hasn’t gotten quite the same amount of attention. Before he meandered into the idea of registering Muslims in a database he made a much more ominous general statement:

“We’re going to have to do things that we never did before. And some people are going to be upset about it, but I think that now everybody is feeling that security is going to rule. And certain things will be done that we never thought would happen in this country in terms of information and learning about the enemy. And so we’re going to have to do certain things that were frankly unthinkable a year ago.”

Coming from Trump that hardly merits a second thought. But unfortunately, in the wake if the Paris attacks, this is actually a pretty mainstream view among politicians of all partisan stripes. First there were the instantaneous shrieks blaming Edward Snowden for the attacks, the most lurid coming from ex-CIA director James Woolsey who said, “I would give him the death sentence, and I would prefer to see him hanged by the neck until he’s dead, rather than merely electrocuted.” (Even Trump’s repeated execution fantasies on the stump aren’t quite that vivid.)

And there have been rumors swirling about the use of encrypted Playstation and various other nefarious uses of technology that will have to be stopped immediately. (Of course it was just a year ago that everyone was saying we had to have more encryption in order to protect against the kind of hacking that happened to Sony.) From the earliest moments after the horrifying events, government officials have been publicly speculating that the terrorists used sophisticated methods that can only be thwarted by allowing more government surveillance with fewer safeguards. The usual suspects are pushing to have even more leeway to spy on citizens without due process and if history is any guide, they are very likely to get their way.

My colleague Elias Isquith’s fascinating interview with Charlie Savage, NYTimes national security reporter and author of the new book called “Power Wars: Inside Obama’s Post-9/11 Presidency,” about how President Obama evolved on national security and the influence of the permanent national security apparatus, dug into the dynamic that makes that happen.

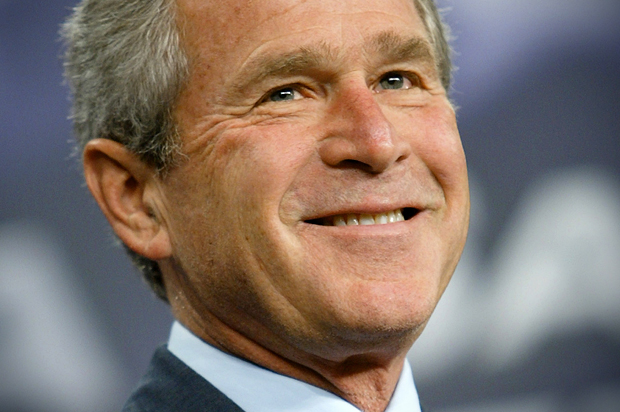

Savage observed that the opposition to Bush’s policies on which Obama and most Democrats ran in 2008, was actually based on two different strands of thought. The first was the opposition to the Bush and Cheney views on presidential power and American military hegemony, which held that the president had massive unilateral authority and that America needn’t adhere to international law.

The other strand of thought comes from the civil libertarians who agreed that those programs were illegal because the president did not have the constitutional authority to unilaterally undertake them, but also believed the programs themselves were unconstitutional on their face.

In practical terms that means that the first group opposed the war in Iraq and torture and warrantless surveillance under the Bush administration because they were not properly authorized. The other groups opposed those policies on the merits of the policies themselves. Together they formed the opposition to Bush’s national security policies and it successfully brought the Democrats to power. But the rationale for opposing those policies were different and Democrats have been confused by this ever since.

However, Savage’s thesis about the two strands shows itself starkly within the political class and it’s something to which voters who care about these issues should pay attention. He characterizes it as the CEOs vs the lawyers:

Bush and Cheney were CEOs by background. They did not put a lot of lawyers in policymaking roles around them. The lawyers they did pick, especially in their first term, tended to have these pretty idiosyncratic views of executive power; and, as a result, they’re able to put in these wide-ranging changes, to have the the government run like a business. Overnight, it’s like, “we’re going to have military commissions”; no further ado; no second-guessing.

Obama and his administration are quite the opposite. Obama and Joe Biden, of course, are both lawyers and showed a clear tendency to put lawyers into policymaking roles around them. And this has consequences, having government-by-lawyer and not government-by-CEO. Lawyers are very incremental; lawyers have to really engage with the other side, because they have to prepare for everybody’s argument; they have to value process. That means they are going to be cautious about changing the status quo. They’re going to be cautious about dislodging what Bush has equipped to them.

I have long thought of this “lawyerly” approach as the “process dodge,” by which I mean that by focusing on whether the president is going through the proper hoops you don’t really have to engage with the policy itself. We saw this a lot with the Iraq war where you had many opponents making the argument that the “real problem” was that the president didn’t get UN approval before going in. They got credit for being against that war even though they hedged their bets by saying what they really cared about was the “process” not that the policy was wrong.

There were similar fights over the policies of torture, surveillance, Guantanamo etc. Some argued they were wrong on the merits. But others opposed the Bush administration over their end run through the OIC and the warrantless wiretapping and insistence that habeas corpus didn’t apply etc. In fact, acting Attorney General James Comey was lauded as a hero for the “Ashcroft bedside crisis” because he didn’t believe the White House had legal authority to authorize internet data mining. The outcome of that brave stand wasn’t exactly inspiring however. The program was suspended briefly and then went on unimpeded under a different legal basis with Comey’s blessing. (Now that Comey is head of the FBI we see the problem with failing to recognize that that those who believe process is everything are often not civil libertarians.)

Savage explained how this phenomenon played out in the Obama administration. During the period he was running for president, many of those policies were brought into line by Congress, which very cooperatively legalized them for the next president. On the trail Obama was obviously one of the lawyerly types who believed that the problems under Bush and Cheney derived from their willingness to stretch the law. He famously came off the campaign trail to vote for telecom immunity from prosecution. This is how the lawyer solves the problem: Make it legal and it’s all good. Savage says that by the time Obama came into office, he felt that most of these thorny problems had come into compliance with the law.

So the truth is that President Obama never really embraced the civil liberties position which would have looked at all the post-9/11 practices through a simpler prism of the Bill of Rights and simple morality. Instead, the congress legalized them or changed them just enough to fit into a legal framework and the practices went on unimpeded. This is how the process dodge works. You don’t have to take a stand on whether or not the policy is right but only whether it is “legal” and those are not necessarily the same thing.

This is where President Obama was when he started his term. According to Savage, when he was tested with the “underwear bomber” case, even the process argument was no longer operative. Whatever mild ambivalence the administration had about entrenching the Bush administration policies was out the window. They succumbed, as all presidencies succumb in the event of threat, to the demands of political necessity and pressure from the national security establishment, or what some people call the Deep State. Savage describes that this way:

I think there’s a very [mistaken] understanding of how the government works — which is that the president just does these things. Obama just does it. Once you work [in D.C.] for a while, you understand that that’s widely oversimplified. Most of the time, the president never knows about what’s going on. It could appear [so] at the most superficial level, but it’s really the 150 or so senior and mid-level executive branch officials that he’s appointed who are making these decisions and grappling with these dilemmas.

What you’re adding to that when you bring up [the deep state] is that, underneath, there’s this permanent state of security officials who have their own sort of world and expertise and turf and bureaucratic interests. All these forces encounter each other in ways that don’t reduce to “Bush did this” and “Obama did that.”

And they are always ready to take advantage of any opportunity to expand their power an reduce their oversight.

That is a very tough problem to solve. Back in the ’70s when the press turned up evidence of government agencies run amok, the Congress attempted to rein them in. The Church Commission in the Senate and the Pike Commission in the House thoroughly investigated and came up with various “fixes” and oversight schemes,at great cost to the political ambitions of those who headed the inquiries. And they were always less successful than people tend to recall. From Kathryn Olmstead’s “Challenging the Secret Government: The Post-Watergate Investigations of the CIA and FBI”:

The liberal, post-Watergate Congress faced an appointed president who did not appear to have the strength to resist this “tidal shift in attitude,” as Senator Church called it. Change seemed so likely in early 1975 that a writer for The Nation declared “the heyday of the National Security State’, to be over, at least temporarily.

But a year and a half later, when the Pike and Church committees finally finished their work, the passion for reform had cooled. The House overwhelmingly rejected the work of the Pike committee and voted to suppress its final report. It even refused to set up a standing intelligence committee. The Senate dealt more favorably with the Church committee, but it too came close to rejecting all of the committee’s recommendations. Only last-minute parliamentary maneuvering enabled Church to salvage one reform, the creation of a new standing committee on intelligence. The proposed charter for the intelligence community, though its various components continued to be hotly debated for several years, never came to pass…

The targets of the investigation had the last laugh on the investigators. “When all is said and done, what did it achieve?” asked Richard Helms, the former director of the CIA who was at the heart of many of the scandals unearthed by Congress and the media. “Where is the legislation, the great piece of legislation, that was going to come out of the Church committee hearings ? I haven’t seen it.”

This was post-Watergate, a time of great reformist spirit. It’s hard to imagine getting that far today. Indeed, as we’ve seen with the squelching of the full Senate Torture Report (with the help of the White House) nothing has changed at all. And as long as this many layered, powerful national security bureaucracy exists this isn’t going to change whether the “CEO” Donald Trump or the “lawyer” Hillary Clinton is sworn in on January 20, 2017.