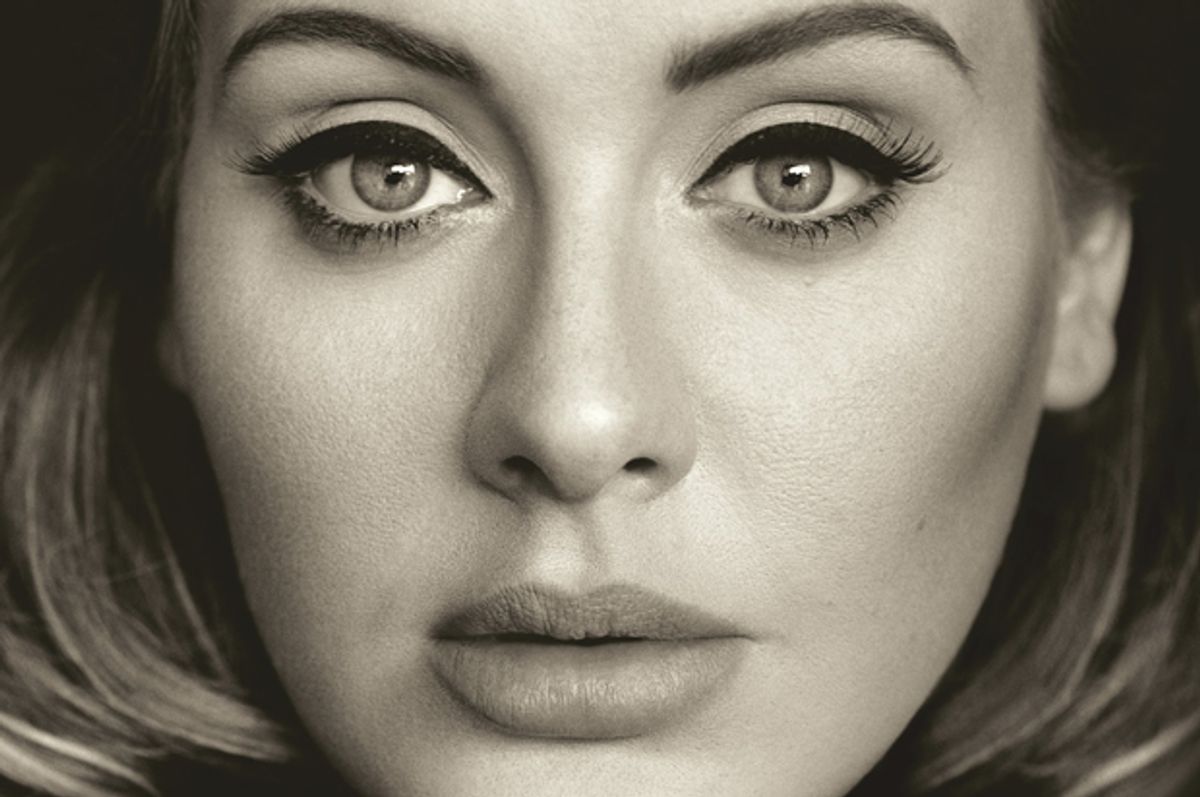

Adele’s first album in four years is set to break records during its first week in release. At a time when “people don’t buy albums,” 25 is on track to sell at least 2.5 million copies—and might even crack 3 million. For reference, Justin Bieber’s "Purpose" (the year’s previous biggest debut) sold 522,000 units in a week, while Adele pushed 900,000 copies of "25" in a day. The all-time-best sales week belongs to *NSYNC’s "No Strings Attached," which boasts an untouched 2.41 million copies 14 years ago.

The universal adoration of Adele has brought together the kinds of people who could never normally agree on anything, so much so that this weekend’s "Saturday Night Live" cheekily suggested that it could keep your family together—or at least from squabbling—during Thanksgiving. While Adele’s appeal amongst older women has long been cited as the key to her success, science shows that our love of pop music’s most transcendently somber chanteuse is hard-wired into our DNA. Adele demonstrates not only the power of sad music but of an emotion even greater than the blues: empathy.

Although Aristotle once suggested that great art offers the pull of catharsis—purging us of unwanted emotions—recent research has offered a different perspective of how our brains respond to sad music. In the New York Times, researchers Ai Kawakami discussed his team’s findings (published in the Frontiers in Psychology journal) in 2013 that music imbued with heartache, tragedy, and suffering evokes different feelings in the listener. Instead of feeling exactly what Sinead O’Connor feels when we listen to “Nothing Compares 2 U,” Kakawami found that the song evokes “vicarious emotions.”

What exactly does that mean to feel vicariously? “Here, there is no object or situation that induces emotion directly, as in regular life,” Kawakami writes. “Instead, the vicarious emotions are free from the essential unpleasantness of their genuine counterparts, while still drawing force from the similarity between the two.”

That definition might seem to be obtuse, but there’s a simpler one. Vicarious emotion is strikingly similar to how philosopher and economist Adam Smith defined empathy—which he called “fellow feeling”—in his essay, "The Theory of Moral Sentiments": “changing places in fancy with the sufferer.” Indeed, another study from the Free University of Berlin’s Liila Taruffi and Stefan Koelsch found that people who are drawn to, experience, and identify with the emotions of others have a strong connection to sad music.

That process is deeply rooted in the process of evolution itself. Like “father of the free market” primatologist Frans de Waal (known for his groundbreaking work on chimpanzee social dynamics) argued, feeling what others feel was a selected genetic trait that helped humans survive in a harsh environment. “First, like every mammal, we need to be sensitive to the needs of our offspring,” de Waal wrote. “Second, our species depends on cooperation, which means that we do better if we are surrounded by healthy, capable group mates. Taking care of them is just a matter of enlightened self-interest.”

These same traits can be witnessed in other species. In a groundbreaking 1964 experiment published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Jules H. Masserman helped pioneer the idea of altruism in primates. His team of researchers found that rhesus monkeys given a choice of pulling a chain to feed themselves and shocking another money or going hungry would rather starve themselves than see a member of their in-group harmed. Primates can even feel empathy for those outside their own species: In 1923, Robert Yerkes psychology Robert Yerkes reported that one of the bonobos he worked with grew a particular attachment to an ailing chimp.

However, there’s something uniquely human about our ability to understand others’ pain. As de Waal writes, “empathy is second nature to us, so much so that anyone devoid of it strikes us as dangerous or mentally ill,” and even the word “human” is inextricably bound to empathy. A favorite moment from John Hughes’ "Sixteen Candles" comes to mind. After spilling all her guts about the guy she likes to Farmer Ted (Anthony Michael Hall), Samantha (Molly Ringwald) is impressed about his willingness to lend an ear. “It's really human of you to listen to all my bullshit,” she responds. Her definition of personhood here, thus, hinges on empathy; her humanity requires engagement and understanding.

If empathy connects us to our environment and those around us—as the University of Virginia’s James Coan suggests, it’s the building block of friendship—it’s also indicative of how we process music. The chemicals our bodies release when we listen to a sad song, oxytocin and prolactin, are the hormones “associated with social bonding and nurturance.” As Dr. Krystyne I. Batcho writes in Psychology Today, artists like Adele can “[enhance] a sense of social connectedness or bonding”—whether that’s in a longing for the past or in an overwhelming gratitude for the present.

These dichotomies envelop the dual meanings of nostalgia, a theme that Adele’s "25" explores beautifully in a set of 11 perfectly-crafted torch songs. If Batcho says that “nostalgia can remind us of who we once were, how we overcame challenges in the past, and who we are in terms of our relationships to others,” Adele’s reminiscence of a previous relationship on “Hello” is a textbook example of the power of empathy: By looking back on the lessons of a failed relationship, the song offers a beautiful allegory for self-love in the present. “Send My Love (To Your New Lover)” only underscores that point: Enjoyment of the present entails coming to terms with your past.

These ideas have always lurked in Adele’s music, even at its most tragic. “Someone Like You” is the anti-Alanis Morrisette: When Adele turns up uninvited, she hopes not to confront you with your ghosts but face them—and move on. Her music has often been billed as depressing, but there’s a quiet strength here that keeps us coming back (and bringing all our friends to listen to Adele with us). Adele’s music is a reminder of our centuries-long journey to become human—whether that’s as apes crawling from the primordial ooze or in staying connected to the world around us—as well as the beauty of that struggle.

In living vicariously through Adele’s music, we can be reminded of what it means to live.

Shares