George W. Bush, tireless during his father’s 1988 campaign, still had to confront his drinking problem if he was to take center stage. Some of the pieces of sobriety were in place. He had been attending Bible study since the mid-’80s and already thought of himself as born-again. He had an ultimatum from Laura, and with his father’s rise to the presidency came opportunities, including the possibility of buying the Texas Rangers. (His great-uncle Herb Walker had once owned the Mets.) The team was a beloved Texas institution. As he told a local news program, “This job has very high visibility, which cures the political problem I’d have: What has the boy done?” He quickly raised $75 million, despite no experience in running a professional sports team. His own contribution was $600,000, but since he put the deal together, he was handed a 10 percent share. So his $600,000 turned into $7.5 million overnight. He would ultimately rake in $15 million.

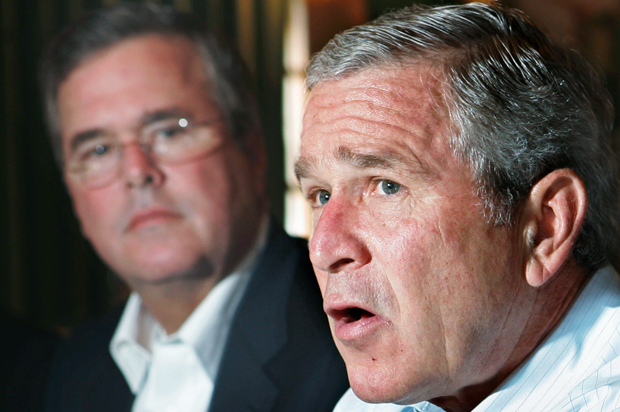

He was now a public figure and worthy of being a gubernatorial candidate. Suddenly a long-simmering family squabble burst into public view. Barbara sent a message to her son, first through aides, and then through reporters. “I’m hoping, having bought the Rangers, he’ll get so involved that he won’t do it.” George W. did nothing to contain his resentment. Also using a reporter to get a message to his mother: “Thank you very much. You’ve been giving me advice for forty-two years, most of which I haven’t taken.” Barbara wanted that year’s Bush candidate to be Jeb, but the younger son wasn’t coming along as quickly as George W. He had a net worth far less than the Ranger windfall, a family that seemed to need him, and a wife who strongly preferred to stay out of the public eye.

The shock of Bush 41 losing the presidency, when it had once seemed so certain to continue to a second term, galvanized the Bushes and cleared the way for both Jeb and George to take their turns at keeping the family in politics. While Jeb started his race for governor of Florida methodically and with the family’s full backing, even permission, George W., in Texas, was asked to back off, partly because his parents felt he would be deflecting funds from his brother, but also because they did not think he could beat Ann Richards, the sharp-tongued incumbent, who had told the 1988 Democratic National Convention that George H. W. Bush had been born “with a silver foot in his mouth.” Florida governor Lawton Chiles, whom Jeb would be challenging, was considered vulnerable. By November, however, polls in Texas and Florida showed movement in unexpected directions. On election night the family’s predictions were inverted: Bush was the new governor of Texas, Chiles was reelected in Florida. George W. got on the phone with his father, who was distraught about Jeb’s loss and continued to lament about what terrible news this was until W. cut him off: “Why do you feel bad about Jeb? Why don’t you feel good about me?”

George had accomplished something his father had twice failed to do—win a state election in Texas—and was now in uncharted waters. Despite the wide array of political positions held by family members, no Bush had served as a governor. He was now the political standard-bearer for the dynasty (and now it really was a dynasty), and there was no familial reference point to guide him. He could be his own man.

In an interview with the Houston Post, he embraced evangelical Christianity. “Heaven is only open to those who accept Jesus Christ,” he said. His cousin John Ellis was compelled to comment, “I always laugh when people say George W. is saying this or that to appease the religious right. He is the religious right.” Even if his faith wasn’t put on display for the sake of votes, it had that effect and appealed to a segment of the Texas electorate that had grown tired of being ignored. It was also a clean break from the muted Episcopalian religiosity of his parents and grandparents. They didn’t talk openly about faith because it wasn’t polite to do so. George W.’s lack of qualms about bearing witness, and Jeb’s conversion to Catholicism, added a new dimension to the Bush dynasty.

And yet he governed Texas much as his father might have. He reached across the aisle to work closely with Democrats and formed a real partnership with his Democratic lieutenant governor. He refused to take a hard line on immigration, even when it became clear that heated rhetoric was paying political dividends in California. He signed a law that guaranteed spots in public colleges and universities to students in the top tenth of any Texas high school graduating class—as a response to the courts’ dismantling of affirmative action. He even proposed offsetting cuts in property taxes with increases in other taxes.

*

The second Bush presidency came down to 537 votes out of 6 million in Florida, the margin of victory in the final tally after the U.S. Supreme Court intervened in the 2000 Florida recount. In this extraordinary chapter in the story of this extraordinary dynasty, the growing vastness and influence of the Bush dynasty became apparent. Jeb was by now governor of Florida and had promised to deliver his state’s twenty-five electoral votes to his older brother. Cousin John Ellis was on the election desk at Fox News, keeping W. informed of the see-saw in the vote count. As the issue moved to the courts, it was President Bush’s former secretary of state, James A. Baker, who headed the legal team. And then there was the eerie historical parallel: fifty years earlier, Prescott Bush had lost in a close election after a bid for a recount was stopped by the courts.

George W. Bush took a hard right turn into the White House. He had once told a reporter, “Don’t underestimate what you can learn from a failed presidency,” clearly referencing his father, and it appeared that the calculation was that what worked in the Austin statehouse would lead only to another one-term Bush presidency. His economic policy was dedicated to a massive tax cut, and he bluntly told Congress he was not into negotiating. Even when he became a wartime president he continued to cut taxes, grandly adding to the federal deficit.

In a sense, however, the Bush 43 presidency began again on September 11, 2001, with him standing at Ground Zero, megaphone in his hand, telling the firefighters and police officers, “I can hear you. The rest of the world hears you. And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.” At that moment, he was the most respected man in America, perhaps in the democratic world.

There is no more far-reaching aspect of the Bush presidencies’ competing legacies than the two wars in Iraq. Bush 43’s war undid much of the legacy of Bush 41’s war—the undoing of the Vietnam syndrome and the return of global respect for American military might. George W.’s war demonstrated the limits of American power, turned America’s voters against overseas deployments, and emboldened America’s enemies. As the rationale for going to war was repeatedly undermined by new information, it allowed public imagination to fixate on a truly awful contention that this war was really about a son trying to prove himself to his father. It should not have been a serious charge, yet George W. didn’t help when he said things like “After all, this is the guy who tried to kill my dad,” a reference to an assassination plot that was likely hatched in Saddam’s Iraq.

*

Jeb was finally elected governor of Florida in 1998, reelected in 2002. As governor, he was by most yardsticks more conservative than any of the other Bushes. He relentlessly cut taxes, by $19 billion, and routinely vetoed new spending—to the tune of $2 billion. He added over a dozen new laws to expand the rights of gun owners, including the controversial “stand your ground” law. He stood fast against legal protections for gays and lesbians, ensured that vouchers were included in his education plan, dismantled affirmative action via executive order, and privatized Medicaid. His two positions that were a hair shirt for conservatives were immigration (he wanted a pathway to citizenship or permanent legal status for the undocumented) and education (he backed the Common Core state standards).

What is in the dynasty’s future? There have been two Bush presidents. Will there be a third? A fourth? Beyond 2016, Jeb and Columba’s son George Prescott (known as “P” in the family) works a political career in Texas; a lawyer and former public school teacher, he was elected Texas land commissioner in 2014, an obscure job that apparently is politically important in the state. He is a cofounder of Hispanic Republicans of Texas: by heritage, a Bush is eligible to become the first Hispanic president.

The Bushes still must confront “the curse of the presidential dynasty.” Not all dynasties wish to include a president on their family tree. Most are content with senators and governors. But there have been six dynasties with presidents: Adams, Harrison, Roosevelt, and Bush, two; Taft and Kennedy, one. (Discount the Harrisons, to whom having a president was a semi-accident.) Each family with two set out to seek a third (or a fourth, given the two branches of the Roosevelts). In each family with one, a second sought the presidency. All failed. They failed because of the person or the circumstances, sometimes both. Fortunately, there is a book about America’s political dynasties that helps explain what went wrong. If the Bushes reach three, they will be America’s greatest political dynasty.

Reprinted with permission from “America’s Political Dynasties: From Adams to Clinton” by Stephen Hess (Brookings Institution Press, 2015). All rights reserved.